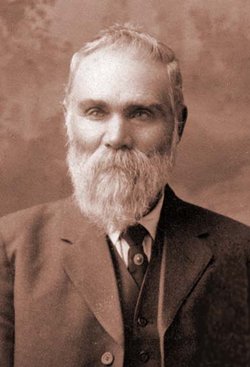

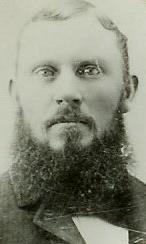

Warriner Ahaz Porter

of

the Mormon Colonies in Mexico

(1848 – 1932)

Warriner Ahaz Porter was born May 20, 1848, at Winter Quarters, Florence, Nebraska. His parents, Chauncy Warriner and Lydia Ann Cook Porter were encamped there with others of Mormon Church who had been driven from their homes in Nauvoo. In the fall of that same year, Lydia Ann Porter crossed the plains to Utah in a covered wagon, taking with her the infant Warriner and four young stepchildren.

After their arrival in Salt Lake City, they suffered through a year of near starvation before Chauncy was able to join them in the fall of 1849. Soon after settling in Salt Lake City, he was assigned to manage a sawmill in the Mill Creek area south of the city. In the autumn of 1854 they moved to Centerville.

The settlers living in Centerville during those early years were beset by many hardships and privations. Food was very scarce, and cloth or wool for weaving was almost impossible to find. For this reason, young Warriner worked as a farm laborer at the age of seven, using his earnings to help with the finances of the home. His formal schooling was very limited, as school was held for only two or three months a year, during the coldest weather when there was less demand for manual labor.

In 1858, Chauncy Porter moved his family to Morgan County, where he went into business with his brothers running a sawmill. They later founded a community know as Porterville. Once again, Warriner was denied a chance for the education he desired so much, but he learned a valuable lessons in knowing how to work with his hands, and grew up strong, independent, and able to support himself at several occupations.

In Porterville there lived the family of Richard S. and Elizabeth Norwood. Through the years of growing up together, Warriner and Mary Malinda Norwood fell in love. They were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, on October 5, 1867.

Warriner had been raised in a home where plural marriage was accepted as part of his religion. He was sincerely convinced that it was right, and therefore on July 21, 1873, after he and Mary had three children, he married Martha Norwood, Mary’s younger sister.

The people in Porterville made an attempt to organize themselves in the United Order. The experiment lasted only 18 months, but the Porter family believed this to be the right way of life, if people could only learn to live its principles. Warriner sold his home and farm and moved to southern Utah were the United Order had been set up in the small town of Orderville, Kane County. Each adult in the Order was assigned to work at the task best suited to his or her talents. Warriner worked in the cabinet and carpenter shop and later became the manager of all furniture making in the Order.

In addition to this work in the Order, Warriner was busy in church and in civic affairs. He served as a Ward Teacher, Sunday School Teacher, a member of the Stake Sunday School Superintendency, and a High Councilman. For a time he was the sheriff of Kane County. Warriner always felt that the time years he spent in Orderville were the most pleasant of his life.

While living in Orderville, Warriner married his third wife. On April 23, 1879, he married Rachel Ann Black, a daughter of William Morley and Maria Hansen Black.

When the United States Congress passed laws against plural marriage, it became illegal for any man living this principle to vote, to hold public office or to own property. Men were hounded, persecuted and even imprisoned. So these good men who married in the sincere belief that they were doing right were forced to make a grim decision. They must abandon the wives and children whom they loved, or they must seek some other locality where they might live together as families, free from persecution. After asking advice from the President of the Church, Warriner decided the only solution was to take his family, leave the United States and settle in the Mormon colonies which were being established in Mexico.

The summer of 1889 was spent in preparation. Property must be sold and business affairs settled. Clothing must be provided for two years, and wagons teams and supplies must be assembled. At the time the Porter family began the exodus to Mexico, Mary had eight children, one of whom was married. Martha had four living children, the oldest just 15 years old, and Rachel’s four living children were all under nine years of age. Each of the wives was leaving behind a small grave, for each had lost a child. They had no hopes that they would ever again see the friends and family they were leaving in Utah, so the start of the journey was tinged with sadness.

On October 3, 1889, the long line of wagons left Orderville. The Porter family traveled with a good friend, Christopher Heaton, who later married Phoebe Ellen Billingsly, a sister to Mary and Martha Norwood. Tragedy struck within weeks of their departure. On October 28, Warriner Eugene, Mary’s oldest son, died at Black Rock crossing of the Little Colorado. He had not been in good health for a long time, and the hardships of the trip overtaxed his heart. The grief-stricken father and brother retraced their way back about three miles to a small station where they were able salvage enough lumber to make a simple casket. He was then carried another 10 miles to the town of St. Joseph, Arizona. Some of Warriner’s people lived there, and it was a great comfort that they did not have to bury him among strangers.

After weary weeks, the travelers reached Deming , New Mexico. Some miles beyond Deming, they were required to pass through customers. A bond was set on all their property with instructions that they must return within six months, bringing each item of property to prove it had not been sold in Mexico. In this way the bond would be lifted.

After crossing the border at Las Palomas, they followed the Boca Grande, traveling along the west bank until they reached the Mormon settlement at Colonia Diaz. Before they could rest, however, they had to go on to Ascension to report to the Mexican Government. They arrived there on December 17, 1889.

Warriner returned his family to Diaz and then went on a tour of the colonies of Dublan, Juarez and Pacheco to decide where it would be best for them to settle. The mountains near Pacheco were covered with tall pines, the first Warriner had seen for many weeks, and he felt that this was the place for him. Hence, on February 3, 1890, the Porters and Heatons settled in Pacheco on a three-acre flat near the river and under the hills on the northeast side of town. They tunneled back into the hill to make dugouts, stretched out their tents, and by using the wagon boxes for bedrooms were able to settle into temporary quarters.

Because of his skill as a carpenter, Warriner found a job building a millhouse near Juarez. But before the task was more than started, he was stricken by a severe attack of chills and fever which left him unable to work for over three months. Another three months was spent in returning to lift his bond in Deming, so the first years in Pacheco were lean ones. Most of the bread was made from corn grown by the Mexicans which had to be hauled 40 miles over almost impassable roads. This corn bread with Mexican beans and molasses made up the major part of their diet. Deer and turkey could be found in the hills, but the men could spare little time for hunting.

By the fall of 1891, through much back-breaking effort, the families had adequate housing, a good crop of corn and potatoes and a vegetable garden. A team and tow of the wagons had been traded for milk cows, so living conditions began to improve. Warriner found, however, that the little farm had insufficient water in the dry season, while the rainy season brought floods roaring down the canyon to wash out dams and ditches.

When they received an offer of land in Cave Valley, the Porters and Heatons sold the farm and moved, arriving in Cave Valley in the spring of 1892. Warriner bought a house and lot with a nice orchard and also a small farm. Then he and Chris Heaton went into partnership and bought a combination shigle and grist mill and they began to prosper.

During the summer of 1893, Martha Porter became very ill. On August 21, she died, leaving four children, one of whom was married. So once again the Porter family was plunged into sorrow. The three wives had lived together in complete harmony. The children hardly knew which mother was their own. Mary and Rachel took Marth’as children and raised them with the same love they showed toward the children born to them.

Cave Valley was organized in the United Order early in 1893 with Christopher Heaton as President and William Morley Black and Warriner Porter as Vice Presidents. When the Order leased a sawmill near Pacheco, Warriner was assigned to manage it. For two years, he and Rachel lived there while Mary kept things going in Cave Valley.

Christopher Heaton was killed by Mexicans while working at the manufacture of molasses in the Casas Grandes Valley. Warriner was stunned by this loss, as Chris had been a brother as well as a good friend. Phoebe Ellen, Heaton’s wife, moved her family back to Utah.

William M. Black was then made President of the Order, but it was not to last much longer. The settlers were forced to leave their homes because of a misunderstanding about financial arrangements. The Order was dissolved and the settlers moved back to the other colonies. With others, Warriner chose to move to Pacheco.

A short time before Chris Heaton’s death, Warriner had bought his share of the mill. But tragically, just after making the final payment on it, the mill burned to the ground.

While living in Cave Valley, four more daughters had been born. Mary’s daughter was the last of her 11 children. The first of three daughters born to Rachel during this period lived only a few weeks, so there was another small grave to leave behind.

The move to Pacheco necessitated the buying of a farm, as all the Church land under irrigation had been taken up. The farm that Warriner purchased contained a very good site for a water-powered mill. The dam which had furnished water for this area had been washed out, leaving the farms with and the mill high and dry. Warriner offered to rebuild one third of the dam if other farmers would help with the rest. It was finally agreed that each famer should pay for his share according to the size of his farm. Warriner’s farm was of such size that he ended up being responsible for building two-thirds of the dam and two-thirds of the upkeep of the ditches. When a water company was formed he was logically elected president.

After moving his families to Pacheco in 1897, Warriner returned to Cave Valley and gathered up all of the equipment which had not been destroyed in the fire with the mill. He was also able to salvage enough lumber from the old home to build two rooms on his farm. By constructing a workshop near the mill, he provided adequate shelter for his families. During the next three years Warriner and his boys managed to add eleven rooms to the house. This home served as comfortable living quarters for both families. There was an enormous living room in the center which was shared by both families, while on each side were the private living quarters, so that each family could have its own individuality. This was a happy time for the family, marred only by the death of Rachel’s year-old son on August of 1899.

In 1903 Warriner sold the shingle mill, keeping the little gristmill to grind his own grain and that of the mountain settlements. He purchased a sawmill and was soon selling lumber throughout the colonies. This mill was operated near Garcia for a time and was then moved to Pacheco. In 1905 it was decided to move the mill back to the boundary line between Pacheco and Garcia, locating near the head of Round Valley Draw. His sons were now able to do most of the milling, while Warriner drove a four-horse team, hauling lumber to the various settlements.

Then disaster struck again in the form of the worst flood ever to hit the valley. It tore the mill from its foundation and carried with it over 50,000 feet of lumber which was scattered in all directions. Once again this intrepid pioneer gathered up the pieces and started over. The mill was rebuilt a few miles down the canyon, although it meant a debt of over $1,000, an overwhelming amount for those days. After the mill was completed, Warriner went into partnership with his son, Omni, who then took over management of the mill.

The Pacheco Land Company was formed about this time for the purpose of assisting settlers to purchase their land from the Church and owning it on a private basis. Warriner was chosen president of the company and spent many hours of his time helping to complete the negotiations.

The Porters met with another business failure when they took a contract to float a large amount of timber down into the Casas Valley where it was to be milled at the railroad. They had somply taken on more than could be accomplished and so were not able to fulfill the contract.

The immense financial loss of this experience really hurt, but it seemed as nothing to Warriner compared to the loss of his wife Rachel. She died on May 5, 1906, just eight days after the birth of her 14th child. The baby daughter lived only one day. Rachel left 11 living children, one of whom was married and one living away from home.

It was hard to adjust to this loss, but as always, their faith gave them the needed strength. Mary, now 55 years old, became a 2nd mother to Rachel’s children, just as she and Rachel had for the children that Martha had left. Of the three families, there were four boys and ten girls still at home. With a family of this size, Warriner could not afford to be idle. He tunred the sawmill over to his sons, keeping a one- half share, and operated the shingle mill as well as doing carpenter work, cabinet building, and farming.

Somehow, Warriner always found time to carry his full share of responsibility in church and community. He served as President of the Pacheco Land Company and as a school trustee, and was always on hand to help with community improvements. His church positions included being a teacher in the Ward, a Stake High Councilman, a Stake Missionary assigned to visit all the Wards, and many other callings through the years.

In 1910, a terrible epidemic of typhoid fever rated through the colonies. Rachel’s daughter Hortense, a lovely girl of 20, was stricken with the disease. She died on August 30, 1910. It was a great blow to lose her in her young womanhood.

In 1911 and the early months of 1912 Warriner spent a great deal of time and money in a complete remodeling of the shingle mill. He had no sooner put it into operation than they were forced to leave it. The civil war in Mexico was growing worse and the Mormon colonists were ordered by their leaders to leave the country. They were given 36 hours in which to reach the nearest railroad, 35 miles away. Each family was allowed to take only a small amount of clothing and bedding and just enough supplies to get them to El Paso.

Thus, on July 30, 1912, the Porters took their departure from Mexico, leaving an estimated $30,000 worth of property, none which was recovered in Warriner’s lifetime. After settling his bills and collecting the little he could of money owed to him, Warriner had $17.00 in his pocket with which to move 7 people over 1,000 miles. His married daughter and her family, number six, also traveled with them, making Warriner responsible for 13 people.

How they accomplished this is another story in itself. But through their faith and their industry they succeeded. Because some family members had previously moved to the small town of Grayson, in southeastern Utah, it was decided to move there. Warriner and Mary Porter lived in Grayson, now Blanding, in San Juan County, Utah, until 1922. Then they moved to Salt Lake City where they spent their declining years working in the temple.

Mary passed away on September 10, 1929, at the age of 78. Warriner carried on alone, faithful and active to the end of his life, which came on May 28, 1932, just after his 84th birthday.

Warriner Ahaz Porter stood at the head of a numerous posterity. He was the father of 30 children, 10 boys, and 20 girls. At the time of his death he could count 125 grandchildren and 55 great grandchildren. Although the last years of his life were spent in poverty in a financial sense, he was wealthy in those riches of life which count the most.

Carol P. Lyman, granddaughter

Stalwarts South of the Border Nelle Spilsbury Hatch, page 537

Mormon Colonies in Mexico