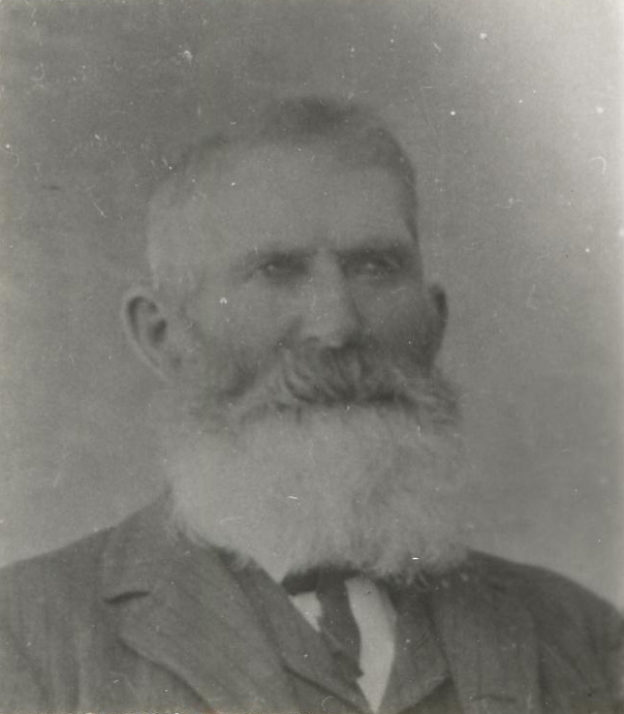

John Fenn

1863-1921

John Fenn, a rugged adventurous pioneer to the Mormon colonies in Mexico was a native of England, born in Eaton Bray, Bedfordshire, April 2, 1854. His father, George Fenn, of Manti, Utah, was serving as a Mormon missionary in the area of his homeland of Bedfordshire. His mother, Eliza Dyer Ward, a young widow with a small daughter, Ann, married George in 1853 at Eaton Bray.

After being released in the fall of 1854, Elder Fenn, his wife, Eliza, stepdaughter Ann Ward, now six years of age, and baby son John sailed on the ship William Statson April 26, 1855 and stopped off at St. Louis, Missouri. Here they received love and help from John Fenn, the 75 year-old “patriarch” who had left England in 1851 intending to come to Zion but arriving in St. Louis, Missouri, in ill-health at the age of seventy-two was unable to continue on to Utah. He opened his home in St. Louis to many of his descendants who arrived with weakened bodies half-starved from their rough sea voyage. Baby John became very attached to his great-grandfather and namesake. John’s little brother, Alfred, was born July 13, 1856, at St. Louis.

In 1857, at Conference, John’s father, George Fenn, was called to settle at Genoa, Nebraska to help establish an important “lifeline” to the steady streams of immigrants. This would be the first rest-stop for the Saints going west from the Omaha-Council Bluffs area (then Kanesville). In 1859 this little family, along with all the other settlers, were cruelly driven out by the Indian Agent.

Eliza was expecting and in delicate health. Her heart was heavy as she gave a last look at the burning ruins and the area where her baby son, Walter, had been buried sixteen months previously. The journey back to Council Bluffs, Iowa, of over one hundred miles was a trying, uncomfortable experience. Six weeks later, Eliza Fenn gave birth to twin sons while the husband and children were hauling wood to keep warm. The mother and babies died and were buried in the same coffin. This was a severe shock to the little family. By this date the death toll of Fenn relatives had mounted to twelve souls, all attempting to get to Zion.

In the spring of 1860 this motherless family, consisting of George Fenn, age thirty, Ann Ward, age twelve, John Fenn, age seven, the principal character of this writing, and Alfred, age four, joined with the Saints who were coming through Utah with Captain John Smith’s ox team. They settled in Provo.

That same year, in the fall of 1860, John’s father took Sarah Ann Jarvis as his wife. From this union John Fenn gained five sisters and one brother. At the request of President Brigham Young the family moved in 1862 to Gunnison, Utah. Here they lived for seventeen years, experiencing much Indian treachery, especially during the Black Hawk War.

As a young single boy, John freighted with his own wagon and team from Gunnison, Utah and other communities to Pioche, Nevada, the nearest railroad point. At the age of twenty, on August 3, 1874, John was ordained an Elder by Daniel H. Wells and married Matilda Sorensen that same day. His wife had told him that she would not marry him unless he took her to the Salt Lake Endowment House.

From Gunnison they moved to Salina where John ventured into several businesses. At one time he had a salt mine and boiled salt. In 1884 he was running a saw mill in the mountains. He was very successful financially there. Five children were born in Salina: Annie, September 23, 1875; John Alfred, September 26, 1877; George Alma, September 29, 1879; Joseph Hyrum, December 17, 1881; and Sarah Eliza Fenn, November 29, 1883. About this time the law of polygamy was being practiced among the members of the Church and John Fenn was contemplating taking a plural wife. Lucy Ann Brown Lindquist had been divorced and had one living daughter, Lucy Ann Victoria Lindquist, age six years. John seriously considered both his and her situation. He was prayerful about this undertaking and he heard a voice which said: “If you want another wife go ahead, but don’t trifle with the principle.” I suppose this meant, marry for the principle and not for the lust of it. He wouldn’t have married her if it had not been right to do so. They were married in Salt Lake City, on January 10, 1884.

On December 8, 1884 Lucy gave birth to a baby girl, Emma. As soon as the marshals who were federal officers heard of this birth they were determined to arrest either the wives or the husband. This birth took place in Washington, near St. George, Utah, en route to Arizona. The officers were paid the handsome bounty of $500.00 per head for the capture of the husband. So in order to escape being imprisoned, one or the other wife had to live on the “underground.” Consequently Lucy, the second wife, lived in obscure shadows in numerous places always under threat and struggle. This situation became so serious that it set off a chain of moves that seemingly never ceased. John Fenn was so well known by everyone in Salina that he had to disguise himself when he went there. He sometimes had to hide out by retiring to the timber until after sundown for fear the marshal would return. At times while traveling he had to walk at a hiding distance from the teams and wagons.

In January, 1885, when baby Emma was almost two months old, John moved Lucy to Arizona and joined a company of Saints who were going to Mexico. Apostle George Teasdale was in this group. He had on chaps and avoided being captured by the marshals by passing as a miner. It was a nice trip. When we arrived at the timbers where there was snow and mud, Brother Teasdale would walk and sing hymns.

Finally, we arrived at Colonia Diaz. On one occasion, in the camp at Diaz, while sleeping in their covered wagon, a voice awakened John and said to him if he wanted his wife, Matilda to live, to pray for her so he awakened his wife Lucy, telling her that Matilda was very sick. He started to get Apostle Teasdale and the camp up, but this voice said for him to pray, so they kneeled in bed, and at that very time she was made well. Up in Salina it was midnight and twelve women were in the room. They said, “Poor sister Fenn is gone.” That was when Dad got up and prayed. She came back, and got well. We stayed only a month and a few days in Mexico that time. Next morning, all were off for Utah.

When we reached the Colorado River at Lee’s Back Bone, they shot off a signal with a gun and Brother Johnson came with his little boat. He said, “I always take the women folks over first.” They had the animals swim across. The wagons were taken apart in order to get them across. There was one whirlpool after another. He said he had never seen so many at one time. Brother Fenn came with the last load. He said he was ready at any moment to pull off his clothes and swim. The current was very dangerous. Driving up and down the steep banks of the Colorado River in order to get to Utah, the brakes not holding, is an experience so frightening that the next trip, if it were possible, you prefer to walk.

After four months, having returned to Salina to get Matilda and family, all moved to Mexico. It too was a long tedious trip. We traveled in our “big outfit” and didn’t have to do the cooking. Arriving again in Diaz, he bought sixty acres or lots, and built two rooms with a willow and mud roof. It was hard living in Mexico for there was little to be had. The $2000 in twenty-dollar gold pieces he had brought didn’t last long caring for the two families.

Again they returned to Utah. For the next two or three years both families lived in a tiny community known as Pleasantdale, Piute County, Utah. John Fenn was well known by all who lived in Salina. He had to leave that area in such a hurry, that he sold his property for whatever he could get out of it. In fact he was never able to collect all that was owed him.

One time, about 1887, Pa, Ma, and Tilde, (as they were affectionately called) were traveling south, having camped in the mountains with their teams and families.

As Mother told it:

Pa was off getting some money that was coming to him down in Rabbit Valley, I had a dream…. in this dream the deputy marshal came to camp. I woke up and asked the Lord what I was to do. Then a voice came to me and told me to send Aunt Lucy, Pa’s second wife, to Box Creek. I got out of bed and spoke to Lucy and told her the deputy marshall would be here before sundown after her. She said that it was just a dream and didn’t amount to a thing. I had dreamed that the deputy knew Pa and Aunt Lucy, but didn’t know me. I asked Lucy, “Do you know where Box Creek is?” “I know,” she said, “but it’s just a scheme of yours to get me away so you can have John to yourself!” (Matilda said she didn’t know where Box Creek was). I told her if she would go I would let George, my son, take the team and take her. At that moment Tory, Aunt Lucy’s oldest daughter, and Pa’s stepdaughter, woke up and said, “Mother I dreamed that the deputy marshall came and got you!” “Well,” Lucy said, “I’d better go then.” I sent my boys up in the hills to get the teams. We prepared breakfast while they were gone, and as soon as possible we got them off. This left myself, my children, Annie, Joe, and Sarah in camp.

About sundown, as I had dreamed, here came the marshal. He rode up to the spring on his horse with a badge on just as I had seen him in my dream. He came up to camp where I was baking bread and said, “Good evening madam, where are you traveling to?” I told him to New Mexico. “Have you any sheep or cattle around here?” I told him all we had was two cows a team and a wagon. I had sent Sarah and Joe after the cows to bring them in to the spring to water. I was sure that if the marshal came they would ask the children what their name was, so I had told them to say Sorensen, (my maiden name) if he asked them. Joe was six years old and Sarah was four. When the marshal heard the bells on the cows coming over the hill he thought it was Pa, and started over to meet them. He asked Joe where his father was. Pa had gone to Rabbit Valley, but Joe told him Manti. Then he said, “What’s your father’s name?” Joe said, after studying a moment and forgetting Sorensen, “I forgot.” The marshal said, “You ignorant little fool!” and rode off.

That night a terrible thunder and rain storm came. I was alone with the children. Early next morning I saw a man coming over the hill. He looked like a tramp with a gun on his shoulder. I was very frightened with no man in camp. I wondered what that old fellow would do. As he neared the camp I discovered it was John, my husband! I hurried to him and told him to retire to the timber, as I was afraid the marshal would come back. I took him out some breakfast, and he stayed hid until about sundown. We then harnessed up, and being short of food, prepared to leave. We were not in sheep country, but a sheep came up over the hill, and we killed it. While we were dressing it out the cows strayed. Pa took the lantern and tracked them; they were headed on their way home. We left that night for Box Creek. I drove the team. Pa went on horseback through the hills. Annie, twelve years old, drove the cows. We traveled all night.

Next morning we arrived at Koosharem. There was a celebration up at Fish Creek. People were gathered. A couple of marshals came by, but as there was no man they did not molest us. From there we went to Box Creek where we found Aunt Lucy. Pa came and we stayed all night. The following morning we took off for Mexico. We settled in Colonia Diaz, Chihuahua, and stayed there the rest of that summer. Pa had rented his place and sheep while we were gone. However, not long after we had arrived in Mexico we heard that a man had logs for a house and was going to jump our place. John Fenn apparently did not have legal title to his place in Mt. Pleasant Creek. We hurried back and the man, hearing of our return, left. Two weeks later, on November 14, 1887, Moroni was born.

Soon, the marshals became tougher and, as one can see, the Fenn families never remained very long in one place. John was often dubbed, “The Rambler,” “The Wanderer,” or the “Rolling Stone.” He couldn’t wait for the grass to grow up under his feet. He was forced to live this way soon after he was called to participate in the principle of plural marriage. The spirit of persecution and hatred became so great that he knew but a few short periods of peace and contentment.

In order not to lose his dual citizenship in the United States and in Mexico, John stayed in the United States for about six months at a time spanning two countries many times until the year 1892. The amount of traveling he did would dwarf that of a military man of his day. In Mexico, John Fenn went into freighting in a big way. He bought large freight teams. He freighted from Nacozari to Naco and Cananea, Sonora, with six to eight mules pulling two connected wagons. When Moroni was eleven and Alvah was nine, their father put them to freighting. It took them seventeen days to make the round trip. “For two years,” Alvah recalls, “we were up at four a.m, and worked sometimes until midnight. I guess I was picked on the most. Seems Dad always took me along, when he went to freight. Of course he believed in ‘not sparing the rod’ (raw hide whip). When the others were in school I was on the freight road.” After the freight (produce, feed, hay etc.) was unloaded at Nacozari, on their return trip to Naco, they carried copper bars which weighed from 300 to 400 pounds each. These boys did their own cooking and caring for their animals. They usually made the trip by themselves. In those days it was “Root Hog or die” and it took the children as well as the parents to make the living. John Fenn had six wagons going some of the time.

During this freighting period the families or part of them lived for a time at Naco, Cos Station, and later at Calabasa Flat. Cos Station was about half-way between Naco and Nacozari. At Calabasa Flat we built a corral and got permission to milk range cows and sold the milk, butter and cheese to the passersby. We had a great time riding horses, gathering walnuts, acorns, choke cherries and going swimming. There was a good-sized camp here with the Jespersons, Yorgensons, Fenns and Orin Barney and family, also some Mexican families up in this canyon. Those are cherished memories.

In 1900, John again moved his families, this time to Nacozari, Sonora, where new mines had just opened. Leaving Colonia Diaz, the group traveled through Ojitos, Pinuelas, Las Varas, and Pulpit Canyon to Colonia Oaxaca, Sonora. From there they pushed on through Colonia Morelos past “Niggerhead” and then to Naco, Sonora. The family had several teams and wagons and joined several hundred other outfits hauling supplies ninety miles from Naco to Jimmy Douglas’ new mine at Nacozari. While in Nacozari John bought a herd of sixty-eight cows from John Holstead.

In 1902, the Fenns moved to Colonia Morelos taking their new herd of cattle with them. They bought land on the south side of the Bavispe River near the Orin Barney and William Beecroft farms. Alvah and his brothers were quickly at work making adobe bricks for their two new houses–one for each of John’s two families. The first year we had a nice crop of wheat. I helped Father along with the rest of the boys. We pulled and cut with a sickle five large stacks of wheat. We had 200 bushels of wheat. I will always remember that hard-earned wheat. We ground some on a hand mill. We also had a mill in town. We would take wheat there and get flour, shorts and bran in return.

While living in Colonia Morelos, Moroni went out deer hunting one day. He accidentally shot his gun and the bullet went through his left leg. He lay there for twenty-four hours before he was found. He had nearly bled to death, and it took him some time to recover. His left leg always bothered him and he always had a slight limp. Mother Fenn was blessed with the ability to have dreams that foretold events that were happening or were going to happen. At this particular time that Moroni was shot, his parents were freighting either from Corralitos or Nacozari. The night Moroni was shot, she dreamed that something was seriously wrong with some member of her family. She told her husband about it and he only laughed at her fears. The next night she dreamed again. This time she could clearly see Moroni and that something was wrong with his leg. She also saw a man riding a bay horse bringing them the news. Again she told her husband and the others about the dream, and urged him to turn back to Morelos and see what had happened. John Fenn only scoffed at her and continued on their way. Later on in the day, George Bunker came riding a bay horse and told them the news. The abashed John gave his wife a look of respect and belief and turned his teams back towards Morelos at a fast pace. Never again did he doubt the authenticity of his wife’S dreams.

The great Bavispe flood of 1905 was a mile wide, over the tops of trees. It wiped out almost everything in the upper town of Oaxaca. It washed sand around the trunks of our trees in the orchard until the trunks were covered up. The water was a mile wide from us to town. What a sight to behold! It washed one of our little adobe houses down. Mother was living in it at that time. The men moved her out just in time, the water was ready to run in their wagon box. She had some nice black hens in our little ocotillo coop, but it just bent it over slanting. The chickens stayed on the roosts and were saved. Our crops were all gone. The entire irrigation system was wiped out. The Fenns having lost heavily moved to Nacozari. Traveling home from Douglas, Joseph E. Scott saw cupboards, beds and parts of houses etc., going down the Bavispe. To avoid facing starvation the men and boys went to work at freighting or in the mines, and doing different kinds of work.

Walter Fenn described Morelos as follows:

Now, to us, we were living in a land flowing with milk and honey. We had plenty of milk, butter, eggs, cottage cheese as well as queso blanco (white cheese). I remember plowing up sweet potatoes. Samples of some of them rolled out in front of the plow as big as boulders. They averaged around thirteen pounds each. When we tried to sell them some people thought they were hollow, but they were not. From the sale of our wheat and potatoes Mother bought bolts or rolls of gingham and denim for making shirts and overalls. Mother always saw to it that there was a garden planted. She always had a flock of chickens so she could trade eggs and butter at the store for a few essentials she needed. In these later years we always had a bin full of wheat that we could take to the mill and bring back flour, bran shorts, cereal or Graham flour. Each year we planted enough potatoes to store for the entire winter and seed for the following summer. We usually grew two crops of potatoes a year.

We weren’t to enjoy this peace and self-sufficiency too long, for in the year of 1912 there was an outbreak of a revolution against the Mexican Government in which the government was overthrown and a new administration took over. In order that the Mormon people wouldn’t be involved on either side they thought it better to leave the country and return to the U.S.A.

As Moroni Fenn described it:

In 1912, the Mexican Revolution began. All the ablebodied men were organized and were given guns. I was made a captain in the organization, but before they had a chance to fight, the Church ordered all the Mormons to leave Mexico. The people in and around Morelos got word that a group of rebels were heading their way and that they were stealing, burning and killing everything they came to, so the poor disheartened people loaded what they could onto their wagons and left for Douglas, Arizona. There near Douglas, the American government let them have a little land to live on until they found something better. The Mormons pitched tents, made lean-tos and fixed up whatever they could find to live in at this place which was called Sunnyside. All the odd-looking living quarters were quite a sight to behold, and the residents of Douglas made trips out there to view the spectacle. Curious people from Douglas came out to gaze at them and try to ascertain if they really did have horns as some had heard.

Joseph E. Scott relates:

After the Federal army left, Willard, Charlie (his brother) and I went back with a wagon hoping to get the grist mill (worth $25,000.00). We had spies out on the hills on each side watching for the rebels. One came back saying that the “Red Flaggers” were coming. They were called that because they had four men on horseback out in front carrying big red flags. As we were coming out with our loads we met them about 2 or 3 miles out of town. I can remember old Salazar, the leader. He motioned his men to get into the wagons to search them. We had melons, flour and peaches. We had just one gun, a 45-90. He took it and wrote out a little note saying that they would pay for it after the war was over. He didn’t bother the rest of the stuff. We were sure scared and glad when he told us that we could go on. The Mexicans had taken my room-full of wheat (200 bushels). They had slaughtered all our chickens in the adobe house and just left the feathers and things there. The Government gave us a pass on the railroad to any place in the United States that we wanted to go. We went to Salt Lake City. We went through the Salt Lake Temple, then we went to Provo where the rest of the family was.

After Parley Fenn returned from his mission in May 1913 he decided to return to Morelos and again take possession of properties, rebuild ditches, etc. He and his brothers, Moroni, Arthur, Kenneth and others worked there until the Villa Revolution forced them to go to the U.S. border in November 1915. He married Grace Jarvis April 8, 1915 in Salt Lake City. Six or seven months later he took his bride and Nellie down to Colonia Morelos. They were only partly settled when the four hour order came to leave. There was little time to prepare as the Pancho Villa army was approaching. Grace was making bread which she quickly finished. Arthur was working with molasses which he quickly buried and they dropped everything and left.

They arrived in Douglas and camped for the night. The next morning, Ed Haymore invited them to stop at his home. Arthur took his outfit and went on to his mother’s in Thatcher. In a matter of days (November, 1915), Villa’s troops arrived and bombarded Agua Prieta. There was great excitement in Douglas. The 10th U.S. Cavalry was alerted and kept on guard duty. Afterward, the main part of Villa’s forces moved on toward Naco.

After things quieted down, Parley bravely went back to Morelos alone to see how affairs were. He described the experience as follows:

The army had camped in our yard. Their animals had cleaned the fields, even eating the straw off brush sheds. The dresser drawers had been used for feed boxes. Pictures and valuables had been strewn around or burned and ruined. All grain bins were emptied; all baled hay devoured and everything inside left bare except the cluttered dooryard. The main army had moved on before others arrived with stolen cattle to slaughter. Some thirty head of beef had been killed in the yard and only the choice parts taken. The remainder was left strewn around. The Fenn ranch was a sickening sight!

On the way down to Morelos, Par ley counted seventy dead horses along the road. They had been shot when they had “given out” to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy. At first, at the smell of the dead animals, Parley’s team snorted, shied, reared and tried to run away with him but they became so accustomed to the sight he could almost drive over the dead carcasses before he reached the colony.

Moroni Fenn took his family back to Morelos for a few months in the Spring of 1916 and began farming. They lived in Orin Barney’s empty home. Most of the fighting had subsided, but groups of soldiers were returning to their homes and as they needed food and transportation, they would help themselves to what they needed.

Moroni took his family back to Sunnyside after the crops were in. He went back and forth to Mexico the next two or three years, leaving the family in and around Douglas. It was during this time that he had a contract to haul bat guano from a cave in Mexico. He hauled seven boxcar loads and shipped it to California. The nitrogen in the guano was used for explosives and the phosphate for fertilizers.

Moroni loved Mexico and the people there and felt that it was his home, also he could not stand being away from his family very long, so sometime in 1917 they moved back to Mexico to the Batepito ranch (belonging to John Fenn before the Exodus of 1912). The ranch was not far from Morelos. His older brother, Joe, also moved his family to the same place.

Both Joe and Moroni loved the Mexican people. He was known to give his hat or coat to some unfortunate Mexican and do without himself. This is one reason the Mexican people thought so much of him. The men from Pancho Villa’s army who came straggling by were the very lowest class of Mexicans, always dirty and wretched looking yet they were welcome at the Fenn farm, sharing the food that was on the stove with them. Sometimes the Fenn’s had to get tough and send these misfits on their way. One lanky, long legged unshaven character had to bend out his legs or walk them along as his tiny burro carried him down the road, while a short-legged companion rode a big stallion, both singing of their renegade-idol, Pancho Villa.

It seemed that the Governor of Sonora, Elias Calles, was a personal friend of Moroni’s and there were negotiations and a promise to furnish a teacher and books for the children but the tragedy of the 1918 flu epidemic changed Moroni’s life drastically. With his wife and baby buried and gone and family scattered he turned to other fields.

After the Exodus in 1912, during the Mexican Revolution we left our homes and farms and went to Douglas with the other Mormon families and lived there in government tents for a while. From there we went to Pomerene and then to Gila Valley and lived there for a few years. Later in 1917 we returned to Pomerene and bought a place and built a home.

In 1920, early in April, Grandfather and Grandmother Fenn left their invalid daughter, Geneva, to make a trip to Salt Lake City by train to have some temple work done for Grandmother’s mother, Ane Caroline Pedersen. During this time John Fenn did not have very good health. He had stomach aches and his food would not digest. Eventually food soured in his stomach and would not pass. He went to Bisbee, Arizona and entered the hospital where he underwent surgery. He had cancer and a few days later he died on July 31, 1921, and was buried at Pomerene.

After his death Grandmother Fenn sold the property to Joe Western and with her daughter, Geneva, moved to Solomonville, Arizona to live with her daughter, Sarah, and Orin Barney. There Geneva died in 1923. In 1932 they moved to Mesa, Arizona to live the rest of their days.

They built a home in the shadows of the Mesa temple and began work at the temple. During the summer months when the temple was closed, Grandmother visited with some of her children and grandchildren. She will always be remembered as a kind, sweet-tempered person. She passed away January 29, 1937, in Mesa, Arizona. Funeral services were held in Pomerene, Arizona and she was buried next to her companion, John Fenn. She left a numerous posterity that will always remember her as a good mother, grandmother and a great pioneer.

Bearl Fenn Gashler, granddaughter

Stalwarts South of the Border,

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch page