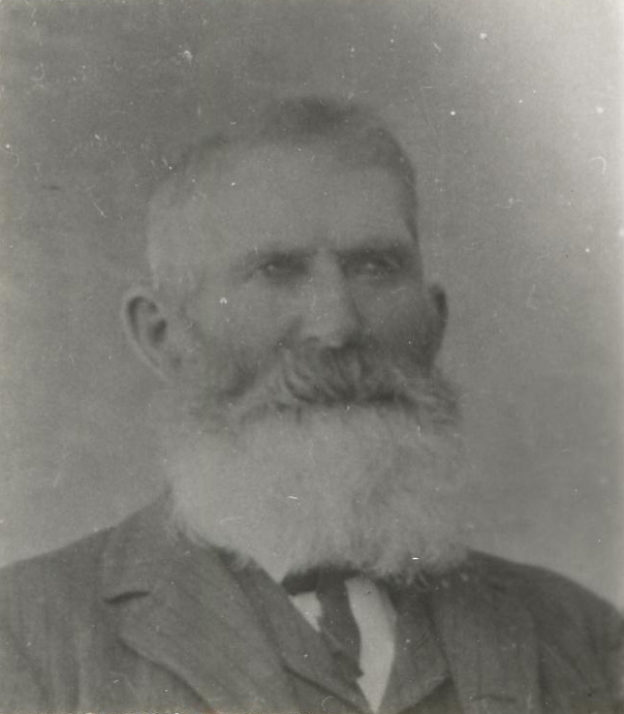

William Rufus Rogers Stowell

1822 – 1901

William Rufus Rogers Stowell was born in Solon, Oneida County, New York on September 23, 1822. He in his early life experienced the stirring events that centered around the vision and subsequent activities of Joseph Smith.

His father, Augustus Stowell, became fairly wealthy. He was a practicing lawyer, owned 260 acres of farmland and many head of blooded horses, all of which brought him a good income.

Young William did not become a member of the Church of Jesus Christ when the rest of the family embraced that faith in 1831, but waited until 1834. By that time the Saints had built the temple in Kirtland, had partially abandoned the town and were gathering to Missouri. In fact, that year saw “Zions Camp” make its historic march to Missouri for the relief of the Saints there. Rumors of calamities and persecutions following the Saints reached the ears of the Stowell family and had a peculiar effect upon William’s father. It caused him to wonder if the Saints were not doing something to bring the persecutions upon themselves, and if perhaps they didn’t merit some of it. When ambassadors were sent to this vicinity to collect means to help the Missouri Saints, he became bitter and refused to give them aid. He was convinced the Saints were planning a rebellion against the government, as they were being accused, and, as a patriot, he wanted nothing to do with a people that was disloyal. So belligerent was he on this issue that he finally withdrew from the Church and became intolerant and finally forbade his wife and children to have further contract with the Saints.

William’s mother endured his pressure for eight years, at the end of which time she sued him for divorce and moved into a home prepared for her by William. In the ensuing proceedings, where the mother contested her rights for justice in the courts, young William was forced to testify against his father, a task that was a trial indeed. But he knew that she was taking the right stand and, painful or not, he had to defend her against his father. The delicacy of what he had to do drove him every day to his knees where he sought guidance from his Heavenly Father. He gained half his father’s property for his mother, and the children were allowed to stay with whichever parent they chose. They all stayed with the mother.

This brought a distinct change in William’s life. He stayed with his mother until September, when with but ten dollars in his pocket, he started out on foot and alone for Nauvoo, Illinois, where the Saints were then settling. Fortunately, he fell in with an outfit which, for his help in exchange for a ride with them, carried him to Chicago. From there he took a bout to Pewaukee, Wisconsin where his sister lived. Here he stayed for two weeks working as a carpenter and joiner in a gristmill and could have stayed in on indefinitely. But Nauvoo was his destination and he was very anxious to see the temple and meet the Prophet. He recognized both when he arrived.

He received a Patriarchal Blessing from Hyrum Smith and was closely enough associated with the Prophet to hear many of him famous utterances. He was at the meeting when Joseph Smith declared himself a candidate for the Presidency of the United States and became well-acquainted with his platform. When missionaries were chosen to go in all directions to campaign for him, he was chosen as one of them. The powerful document written by Joseph Smith setting forth his views was looked upon by William as a masterpiece of vision and understanding of the needs of a free people. With it in his possession, and being set apart along with the Twelve Apostles and a large corps of Elders at the April conference in 1844, he set out to proselyte for the Prophet Joseph. He left in May with Elder William Parshall after having been ordained a Seventy. New York was their destination. They walked, except for a short distance along the Ohio River, approximately 1,000 miles.

By the first of June they reached his old home town. Only eight months had passed since he had left. He was glad to find his mother and family were ready for baptism and gladly performed the ordinance for them. So much had happened in those eight months. His old home had lots its charm, and when he found that his mother and sisters were ready to migrated, he was anxious to Nauvoo.

The martyrdom of the Prophet occurred before he had been in New York three days. This released him from his mission, and with a heart filled with sorrow he turned to the task of helping his family move. There was much to do in a short time: the gathering of crops; trading and selling property; and getting outfits ready to leave while the season was favorable for traveling. They made no secret of their destination when they finally set out, for “Nauvoo” was printed on their wagon cover.

After arriving he married Hannah Topham, a girl with whom he had become enamored before he left, on Christmas day, 1844. Lorenzo Snow performed the ceremony. William continued to care for his mother and sisters even after he moved into a home of his own. He did all he could to push the work on the temple, now nearing completion, as well as carry on his farm work. He succeeded in gathering most of his crops even though many lost theirs through burnings by mobs. All could see that the time was fast approaching when they would have to leave their beautiful city in the hands of their enemies. And soon, preparations for an exodus began.

William Rufus Rogers Stowell was one of the first 100 men chosen to be scouts for the evacuation. They built roads and bridges and mapped out ways to travel. They also took work wherever they found it, in order to obtain supplies for the Saints. He cut timber and fitted wagons for others while doing what he could to prepare his own outfit.

By February the exodus began, and for the first two weeks he worked continuously, ferrying Saints across the Mississippi River. In a fall of snow three inches deep, he and his company of Saints moved nine miles to the bend in Sugar Creek and made camp. There Brigham Young caught up with them and began organizing for the westward trip. William proved a savior to the weak and infirm, for the suffering was intense. Women walked all the way, caring for families at night with no protection other than their wagons. This group of 400 wagons took until April to reach Garden Grove. There they made camp, put in crops, dug wells, and built houses. So industrious were they in preparing a way station for those who should come later that it was not but a few days until the place looked like it had been settled for years. Some of the Saints remained here to keep the crops growing and to help those who were yet to come. In the spring of 1847 William moved on to Council Bluffs. There he stayed until the summer of 1850, raising crops and preparing for their final trek to Salt Lake Valley where they arrived in September, 1850.

William spent the winter in Salt Lake City, then moved to Provo and took up a 25 acre farm. His wife then became dissatisfied and sued for divorce. He granted it and married Cynthia Park the following autumn.

During the next few years he was kept busy settling Indian difficulties and doing military duty of one nature or another. His burdens were increased when he adopted the six orphaned children of his brother and sister. When he finally settled in Ogden, he made his growing family and their care his first concern.

During the Utah War, William Rufus Rogers Stowell was made an adjutant in Major Taylor’s battalion of infantry. He was ordered to the front in October 1857, and not until spring was he to see his home or any of his family. His first reconnoiter up Echo Canyon was a fateful one for, in proceeding up Ham’s Fork for the purpose of getting as close to enemy headquarters as possible, they ran into a detachment of U.S. soldiers who took him and his major prisoners. He remained in custody all winter, part of the time in irons, and was twice the victim of an intended poisoning. Once he tried to escape, but found the hazards of getting through the snow and over the mountain to safety were too much, so he gave himself up and submitted to solitary confinement as punishment.

The suffering William Rufus Rogers Stowell endured was harsh, but in a way his capture proved a blessing for it kept the army from entering the valley before the Saints had time to defend themselves. As soon as he was captured, he made three attempts to destroy a little book he carried containing important instructions from General Wells. On his first attempt to drop it, a voice spoke to him, saying plainly telling him not to drop the book because it would do more good than harm. Unable to understand why he should be advised to do anything so foolish, he determined to disregard the warning and dropped it anyway. But the voice spoke more distinctly the second time telling him not to destroy it and repeating that it would do him more good than harm. Still thinking it was foolishness to listen to such advice, he made a third attempt, thinking he would drop it quickly before the voice could stop him. But the voice was quicker than he, and again he was told not to destroy the book.

When he was searched, the book was among the first things discovered. After reading the instructions it contained, the officers sent for him. He was so discouraged that his feet dragged as he went to their tent. But again a voice whispered to him, telling him to take no thought of what he would say “for it would be given him in that hour what eh should speak.” This brought peace and comfort to his mind and he entered the officer’s tent calm and unafraid.

Words poured from his mouth telling them how impossible it was to enter the valley without great loss of life; the Echo Canyon was not only fortified but that great stones were piled in strategic points ready to be dropped on them; that other valleys were equally well-guarded; that there must be 30,000 Mormons in the hills determined that they would never again surrender to a hostile force. All of this greatly astonished the colonel. William followed his remarks with this statement: “You have the major and myself in your power. You can kill us if you are so disposed, but we are only two, and there are plenty left.”

This interview added indecision to the deliberations of the troops’ officers. Some were sure they could never make it through. Others were for pushing boldly on. They finally decided to go into winter quarters and wait to see what developments the spring brought. That hesitation, followed by the arrival of General Johnston who saw their desperate plight and seconded the decision, was the act that saved the Saints from being forced to use violence to protect themselves. All winter the U.S. soldiers endured half-rations, bitter cold and untold discomforts while waiting for spring and something to ease the situation.

When peace was finally established through the medium of Colonel Thomas Kane, William was released and allowed to go to Salt Lake City ahead of the army and find his family. For eight months he had had no word of them, though they had been kept more or less aware of his condition. He found they had moved south with the great body of Saints, when they determined to abandon their city, and they were now in Payson and Salem living with friends. Both his wives had had babies while he was gone and had suffered many hardships. With only the help of the children, they had loaded their belongings into a wagon drawn by a team of steers, and had made the move south with the body of the Saints. William himself was looking emaciated and half-crippled from carrying irons on his foot. But looking over his winter’s experience, he felt he had been an instrument in the hand of the Lord in preserving the Saints.

William Rufus Rogers Stowell bought land, stocked it with sheep and horses, and broke land with his plow and planted lucerne and corn. Everything he did prospered. His property increased in value when the railroad was completed in 1869, and he raised more farm crops since everything was so in demand for workers on the railroad. By 1884, he was considered by himself and those around him as a thrifty well-to-do farmer.

Then the polygamy raids began. Laws were passed making all who had more than one wife subject to arrest, fine and imprisonment. William went into hiding to escape arrest. First he hid in the Logan Temple where he did temple ordinance work for his family. When he ran out of names and data he had himself called on a mission in the East where he again visited all his relatives in the state of New York. While there he gathered genealogy, hoping that by the time he returned the trouble would be over. But it continued to rage, so he went on a second mission, this time to California. Then he resorted to hideouts in the mountains, dodging in at favorable times to help with the farm work, or give courage to his family. Gradually he came under suspicion as his home and his approach was watched, and he could see the game he was playing could go on no longer. Anyway he was weary of hiding and, in company with his son Brigham, also on the dodge, he went to Mexico. They arrived in Colonia Juarez in February 1889. There they found a critical situation for want of bread and butter. They expense of shipping it from the United States made it prohibitive. The availability of hand-ground corn was unpredictable. The little flour mill operating in Galeana was entirely inadequate. It took from four days to a week standing in line for their turn. The grade of flour was little better than the cornmeal they could make. Naturally every newcomer was hopefully received as they searched for a potential miller.

Whether or not William Rufus Rogers Stowell looked like a “flour” man is not known. But before he was in town an hour, he was approached by his wife’s cousin, William C. McClellan, with a proposition. “Come with me,” he said without further preliminaries. “I’ll show you a natural mill site, a place where the right man can establish an industry that not only will make him a substantial living, but will make him a savior to a bread-hungry community.” They went to a point on the Piedras Verdes River but a few rods distant from the first rock house built in Old Town.

In a few terse sentences McClellan demonstrated how a mill placed at this point of the river could be operated by making use of the canal that had but recently carried water to their farms on the old townsite. All it needed was a rock runway down which the water could run to turn the water will of the mill at its base.

William Rufus Rogers Stowell decided it was a practical idea and felt his search for a home was over.

Making a start was as simple as that. A little time spent in looking the country over, talking with Bishop Sevey and other leading men, enjoying the hospitality of friends and relatives, and his fast-formed plan was ready for action. He bought his machinery when he returned to Utah and hired Peter N. Skousen to haul it in. By the first of June he was back in Colonia Juarez with his family. He disposed of his property in Ogden, had made trips necessary to complete negotiations at the border for emigration, had his plans all made to begin operations on his mill and a home underway for his family.

In late November the machinery was installed. Before Christmas, they were grinding corn and flour. It took only ten months for this 76 year-old human dynamo to complete a project done in the hardest way. Most importantly, the people now enjoyed flour from the first gristmill in the country. What greater sense of power than to watch those large grinders set in motion by the cascade of water as it catapulted down the runway and hurled the great wheel into action. What music could lull and soothe as the hum of those huge grinders as they munched the golden kernels, crushing and passing the on to ever finer rollers, sifting and separating till the velvety whiteness was emitted from yawning hoppers into gaping sacks. What greater feeling of security than to see the sacks piled for home consumption, and to know that at last they had annihilated the proverbial wolf and now had breadstuff in plenteous quantities for their families?

That two-story adobe building became the vortex of a thriving business center, the symbol of a new agricultural life. Farmers raised more and better wheat to exchange for flour. Contented customers returning for service year after year soon made the mill’s storage capacity inadequate, and an adobe annex fronting the western entrance was added. William’s keen insight into business management and his meticulous attention to detail was characteristic of his everyday habits. He was an archenemy of waste, and careful attention to detail was his weapon for fighting that evil. “Shake it over the bran pile,” was a reproof some unthinking customer would hear while shaking his emptied flour sack in the open air. Turning his chickens loose to clean up the waste grain when horses scattered their rations in his yard or keeping pigs fattened on over-full sack leakages all were means to eliminate waste and keep his premises clean. His daily trips back and forth from home to his mill always included a careful check on the dam, headgate, water supply, canal cleaning or possible repairs on his way. And his inspection of the running gears in his mill was a daily task.

When past the three-quarter century mark, wisdom forbade his continuing the strenuous life. He first employed a miller, to whm he later sold the mill and the business. In December 1895, he was ordained a Patriarch, and served in that capacity for the rest of his life. His last days were spent in Colonia Juarez, where he passed away May 30, 1901.

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

Stalwarts South of the Border, page 651

A biographical sketch written by James Little is found here. This biography includes William Rufus Rogers Stowell’s Patriarchal Blessing given to him by Hyrum Smith.