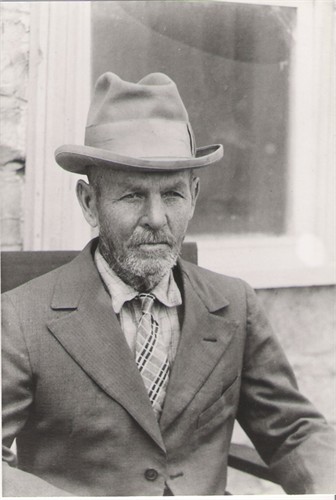

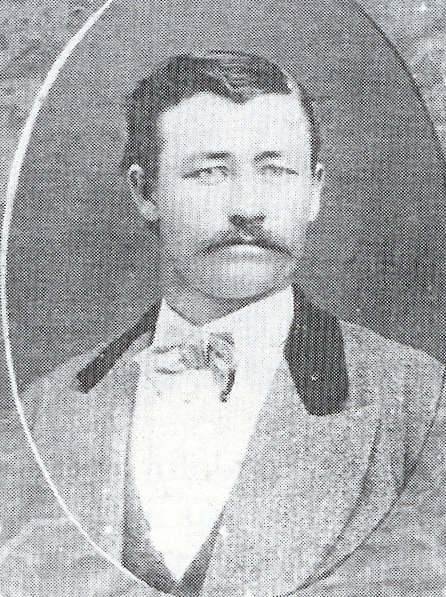

Lorenzo Snow Huish

(1854 – 1937)

Uley, England is the home town of the Huishes. My father, James William, never had a day of schooling in his life. He got his education from the Bible and attending Sunday School. My mother’s father, John Niblett, was a well-to-do contractor and builder who had property and lived in a house of his own. His people also were very well-to-do and lived in an aristocratic manner. My mother, being the youngest child, was raised somewhat petted and proud as well-to-do people were in those days. She loved beautiful clothes. Some of her dresses were so elaborately frilled and ruffled that they could almost stand alone. Avening was the home of the Nibletts which was about seven miles from Uley.

When my father was old enough, he was apprenticed to his relatives seven years to learn blacksmithing and horse and cattle doctoring. He disliked the drenching of cows, especially on Sunday in Sunday clothes, so he gave up the doctoring and devoted himself to blacksmithing. He became very expert in steel work, making tools for miners and colliers. My father went to Avening to work where the Nibletts lived. One day some curios girls came into the shop to see the newcomer. On being introduced to the girls, James said, “The one with the curls is for me,” but Hellen scorned him and tossed her curls high saying, “Not that insignificant boy!” James was only fifteen, just a boy, but Hellen was fourteen, and they were both born in December. This incident ripened into association, then friendship then love, and then marriage, which marriage lasted for 55 years.

There began the branch of the Huish family to which I belong. My father’s people, who were very religious, believed in Jesus Christ as the Redeemer of the world, that by Him the world would be saved and believed the Bible to be the Word of God. But if was possible, my mother’s family was more religious. The Church of England and the Methodist Church were the prevailing churches of England. My mother spoke in tongues on several occasions, and had the gift of discernment and detected an evil spirit. One conference she told President Williams that there was an evil spirit in the room. Presently a man began to holler and fight in agony, afflicted by an evil spirt. My mother also had the interpretation of tongues.

Edward, my eldest brother, was born in Avening. One day the Mormon Elders came to town – Henry Webb and his companion. Father listened attentively. They spoke from his beloved Bible and he believed, commenting to his family later, “If ever I heard the word of God, I heard it today.” They walked nine miles to the meetings, carrying Edward in their arms, to hear more of the restored Gospel. On the 21st of December, 1843, Elder Webb baptized them, and the rest of the family was born in the Church.

After they were baptized, they moved to Bleavenon, Monmouthshire, in Wales. Here they remained for 12 years, hoping to provide better for their ever-increasing family. Here James became Branch President, and Hellen directed the music. Here Joseph, Fanny, and Orson Pratt were born, and here Fanny died. Then came the twins, Lorenzo Snow and Franklin D.

Hellen’s family had named many of their children for apostles of the ancient Church: Peter, James, John, and Bartholomew, and Hellen felt the same allegiance to her new found love, and named many of her children for the apostles of the restored Church. There were Joseph, Orson Pratt, Lorenzo Snow, Franklin D. Richards, and Heber C. Kimball, all honored by name.

In those days there was always the spirit of gathering to Zion. James and Hellen longed for this time to come for them. Finally James was counseled to leave Wales, the home of the tender memories, and go to America and earn enough money to move his family. Many other Elders went with him. They sailed the vessel Tuscarora for 37 days. Hellen was left with five children, one little grave, and another baby o the way. In spite of this she kept busy with the sick. The Powell family, converts of her husband, had typhoid fever, and a tiny infant. She cared for the parents and for the baby. Little did she know that she was keeping alive at her own breast the girl who later would become her daughter-in-law, and marry her second son Joe. Joe and Edward were working now in the coal pits. The twins were four years old, and little Heber was born, when they received the long looked for letter from the emigration fund stating there were sufficient funds to emigrate to Zion.

Mother called the children around her and explained to them that the time had come to go to America and see Father, and not a cough must be heard. She passed the inspection by the ship’s doctor and set sail on the Dread-Naught for that far-away land. Through her faith and the blessings of the Lord, we made not a sound, but after being out a few days, the cough developed in baby Heber, who died in the cold December, and was buried at sea. I well remember, though only a little boy just four years old, seeing a man sew the body up in a canvas sack, put a weight at his feet, and then after the ship’s brief burial service, put it over the side of the ship, and tip it so the body would slide into the ocean. Mother’s grief at this time seemed more than she could bear. She was sustained only by faith and prayer, and the necessity of turning her full attention to me. I had a relapse, and she feared I might join my baby brother in the depths of the ocean. I well remember my mother carrying me around in her arms, but a kind Heavenly Father let me live.

After 21 days on the water, we arrived at Castle Gardens in New York. We looked for Father, but he was not there. Mother was still carrying me around in her arms as I was too weak to stand alone. Mother never lingered long on a disappointment, and immediately took the coach for Frankfort, Missouri. Father had taken the coach for New York, and the two would have missed each other but Orson, who was sitting up with the drier, spied father and stopped the coach. Father raised the shawl Mother was wearing to see the little son born after we left Wales only to be told that he was buried deep in the ocean. But at last the family was again reunited.

While in Missouri I remember seeing slaves sold at auction. Some of them brought as high as $1,500. While here in Frankfort another little boy came to our home, Mother’s eighth child. They called him James. We left Missouri to join the emigration company in Nebraska. Mother walked much of the way across the plains carrying her little one year old baby in her arms, and with me, a little six year old boy, bare-footed, walking at her side. It was a long and tiring journey of four months, and tried the mettle in the best of them. At times it seemed even the oxen hated it.

The Huishes went directly to Payson, an open, unsettled country. Father immediately went to work at a nail factory, which later became known as “The Huish Machine and Furniture Shop.” We lived in a small log house. Florette and Fredrick were born here.

Emma Huish Haymore continues the story:

There was no time for education. Lorenzo learned to the read from his mother’s hymnbook. It was a copy of the 20th edition, published in Manchester, England, in 1840, dedicated to those of the New and Everlasting Covenant, and signed by Brigham Young, Parley P. Pratt, and John Taylor. It was frayed at the corners and badly worn from use. From this cherished volume ‘Ren’ also loved to sing. Often he sang I am a Mormon Boy and felt greater than a King.

Ren was not baptized until he was 14 years old. Now he had the work of a Deacon. He, with Franklin D. Haymore, presided over the quorum. They cleaned the meeting house, collected fast offerings, and chopped wood for the widows. About this time he had his first pair of shoes. They were made out of an old pair of boot tops.

At this age his father took him into the shop with him where he worked for eight years. Ren bought a team and a wagon, and rented a piece of ground from his uncle. This he worked when blacksmithing became slow in the summer.

In 1875, when Ren was 20 years old, and Antha Philmore was 17, they were married. It was a double wedding with Abe Done and Lizzy Robinson. Ren just had $2.50 in his pocket, but why worry, that would get the license! They were married by civil law and later endowed.

Ren loved to round dance, and Antha would rather dance than eat. At this time a request came from the Church that tried their faith. Brigham Young asked all the Saints to “stop round dancing.” Ren and Antha raised their hands to sustain the Prophet of the Lord in this request, and never round danced a gain. In 1876, according to instructions from the Church, the people of Payson were re-baptized in the font on the premises of Daniel Stark, where they renewed their covenants and pledged to observe and keep the rules of the United Order. Fourteen of these baptized were members of the James W. Huish family. Ren and Antha were two of these.

In April of 1876 Lorenzo’s first child, Petrilla, was born. She was always called “Pet.” About two years later a son came, Alfred Lorenzo. Now Ren was not only the father of a man, but also a namesake. And then came Jimmy who lived 16 months and died.

In 1882 Floretta was born, and they nicknamed her “Doll.” Then came Lorena, and two years later, Eva Helen.

About this time Lorenzo was counseled to enter the celestial law of plural marriage. He hesitated and walked the floor all night in prayer and meditation. He had always been faithful to the call of the priesthood, but there was so much involved. About 200 men were imprisoned in the Utah Penitentiary. Young wives could not stay home to care for their little children. The husbands were chased down like foxes before the hounds. Even neighbors cannot be trusted. Children were harassed with rude questions. There were always taught to say, “I don’t know.” Who is your father? “I don’t know.” Where a mother? “I don’t know.” Where do you live? “I don’t know.” They were not only under tension when the U.S. Marshals came, but the constant fear of their coming was equally trying. Every approaching visitor might be an officer or an enemy. Lorenzo asked himself, did he want to plunge into the boiling cauldron of persecution? Could he provide for another family? How could Antha take it? And does he paced the floor and questioned. Could he do it? He knew it was the highest law of the Celestial Kingdom, and he read and re-read Section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants. He asked himself, was Joseph Smith a Prophet? The answer “Yes.” Then this law was true, for he gave it, and Lorenzo prayed for strength to live it.

The Thomas Broadbent family lived in Payson. They were talented and musical. Thomas himself was a violinist, and his character was above reproach. Lorenzo thought he would call on Mary Elizabeth, the oldest daughter, which he did. One time during one of these calls, her younger sister Amy came in. When Lorenzo saw her, he said, “This is the one.” He later proposed marriage. Amy referred him to her father. Plans were made and they started to the Logan Temple. It was a dark day, but no lower than their spirits. Lorenzo thought, if only he could get a witness. He looked up at the lowering clouds wondering if he would be able to make the trip before the storm broke. The face appeared in the dark clouds, he heard a voice say, “I am thy Redeemer.” This was April 8, 1885. They were married by Marriner W. Merrill. As they came out of the Temple the sun was shining and Lorenzo felt he had received a witness that he and Annie would be able to weather the storms of life together, and he’s saying, “Little Annie Rooney is my Sweetheart.”

The Edmunds law was passed in 1882 for bed plural marriage. Now another law was passed requiring that every person taken oath to disregard their families or lose their franchise. Persecution became unbearable. Annie went into hiding as Mrs. Brown. One day she was hiding under the seat of a wagon going from one town to another. She was covered on both sides by quilt thrown over the seat. The wagon stopped suddenly with a jerk, and any heard voices. They were suspected officers of the law wanting a lift to the next town. Annie trembled. They climbed on the seat. Driver cautioned the men to be careful and not kick their feet on the seat, as he had a case of eggs there.

Lorenzo received a call from Box B for the British mission. He armed himself with a standard works, the Voice of Warning, and a hymnbook. He loved the songs of Zion.

Annie was looking for her firstborn, which came in October, three months after Lorenzo had sailed. It was four months old when it died of pneumonia, and any buried it alone by moonlight. She made the closing brought the coffin and got a man to dig a little great. There was no choir, no mourners, just one lonely mother. As a last shovel of dirt was put on the little mound, a sound of footsteps was heard. Annie, startled, expected to see marshals, but saw Helen Niblett with a bouquet of flowers to place on the tiny grave.

Lorenzo returned to the farm, and Annie to persecution. Annie’s first child was born in Santaquin, the next one in Mona, then Spanish Fork, then Spring Lake, marking the trail of the underground. Annie came home from this birth. It was in the cold winter of 1894. This was Emma Geneva. Lorenzo too came home and was detected by the marshals and some of the present. On the 25th day of February of the following year, he was tried in the First District Court of Ogden and was sentenced by Judge William H. King to imprisonment in the Utah State Penitentiary for unlawful cohabitation. He was released on March 24, 1895, one month later, for good behavior.

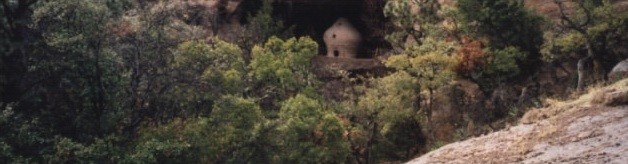

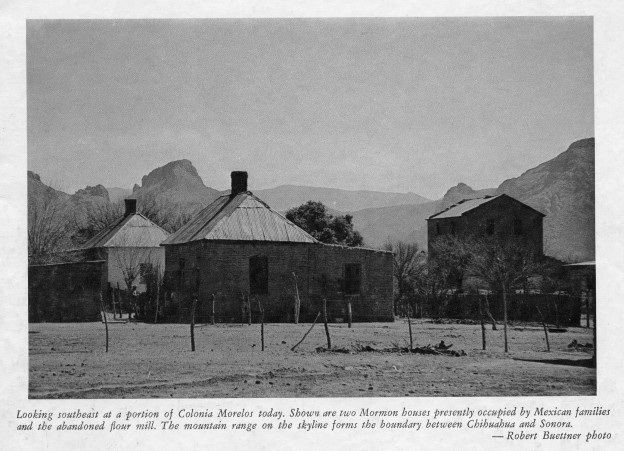

Many of the polygamist families were going into foreign lands to avoid further persecution, and with the hope of being more with their families. A. W. Ivins was Stake President of Colonia Juarez, Dublan, Oaxaca, and Diaz. A tract of land in Sonora was purchased by President A. W. Ivins in the fall of 1899, from a man by the name of Cameron. Cameron had leased the property to some Mexicans by the name of Gavilondo. The purchase price was $15,000 for 9000 acres. Soon after, President Ivins, was about 25 persons, including Apostle Owen Woodruff, dedicated the property as a place for the establishment of a Latter-day Saint colony.

The following is a record of Lorenzo’s journey to Mexico, written by himself:

Left Payson on 13 December, 1899, from Mexico in charge of a company of 50 men and women and children. From Payson were L.S. Huish, E.A. Huish, Alfred Huish, William Huish, Jacob Huber, Earnest Juber, A.L. Jones and wife and family, Edward Jones and wife and family, A. Done and family, Jas. Douglas, Charles Bennett of Beaver, Earnest Tanner, John Done and wife, Mrs. Horace Curtis and family, and Mrs. Abegg and family from Salt Lake, Daniel Snarr and a son Dan, from Salem, Frederickson.

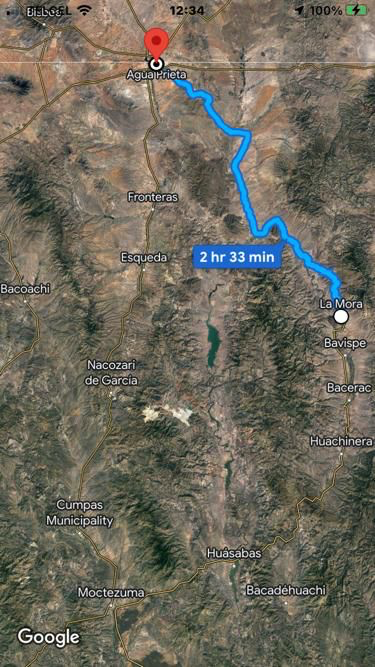

We had three freight cars and two passengers with one wreck and other light incidents. After seven days we arrived safe in El Paso, Texas. Our party then divided, some going into Arizona, some to Colonia Dublan, some to Colonia Juarez, and went to Colonia Oaxaca, all in Mexico. On 11th of January, 1900, the following brothers left Dublan for Batopilas: L.S. Huish and son Alfred, E.A. Huish and son William, D.H. Snarr and son Daniel, Jacob Huber and Brother Earnest. After nine days over valleys and mountains, some of the roughest roads I have ever traveled over, we arrived safe at Batopilas Ranch, Bavispe, River, the first company to arrive, January 19, 1900. On arriving we found one white man on the river, Brother Samuel Lewis, a member of the Mormon Battalion a man in his 70’s, who had preceded us a few days. He had walked from Kansas to the Pacific in 1847. On January 25, Brother Ivins, Pratt, and Martineau arrived from Diaz Conference, to survey the canals and land. On January 26, A.L. Jones and Edward Jones and a son A.L. who had been left in Dublan, arrived also. Brother A.L. McCall from Salt Lake City arrived on January 27, also Samuel V. Jarvis and two sons. And on Sunday the 28th, James Butler and two sons, also Brother Craycraft, Farnsworth, and Cardon. Brother McCall’s wives were the first women to arrive. The settlement was not known as Morelos until 1901.

Elder L. S. Huish was the first to put up a tent on the river, assisted by Elder D.H. Snarr. The remainder of January and up to February 3, 1900, was spent looking out the most reasonable place to make a canal. Up to February 7th and 8th we began to lay out the town into survey lots. On the 10th we began to lay out fields under ditch number 1 and south of townsite. President Ivins having gone to the line near Bisbee on business, having returned, assisted with both. In his absence, Helaman Pratt, counselor taking charge. Sunday, February 11, meeting was called for 2 p.m. at which time, after the sacrament, a branch was organized and attached to the Oaxaca Ward where Elder George Naegle was Bishop, he being present in assisting in the organization. Elder L. S. Huish was appointed Presiding Elder, with Elder A.E. Huish as a branch clerk, after which his good counsel was given by President Ivins, Pratt, and Bishop Naegle.

The Priesthood meeting was held at 4:30 p.m. at which matters pertaining to town field and the allotting of the same was decided. At a meeting held in the evening, the brethren spoke of early times in different parts of Utah, Arizona and Mexico, where they had pioneered. The committee was chosen to appraise the land and ditch work. Monday, February 12, assisted in laying out the cemetery and arranging work for ditch. President Ivins gave L.S. Huish four fine lots in the center of town for the help rendered in surveying the whole project. Some crops were raised the first season.

From this time for several days and weeks, work on the ditch, also cut and made a set of house logs. My time was spent at this work and with my ecclesiastical duties, until May 25. At that day I started over the mountain to Dublan to go from their home. In the meantime having built me a log house, the first in the place. My son Alfred and myself having also done between three and four hundred dollars on the ditch. Spent a day in Dublan, then trained to El Paso on the eve of May 31st, 1900. Arrived home Sunday, June 3rd, found all well at home. Immediately went to work on the farm.

The following Sunday went to Salt Lake City to Young Men’s conference and on other business. Returned in a few days and spent the summer on the farm and in getting ready to move family to our new home. The summer was dry, crops very light, and some failed completely. Sold my hay for a good price, bought a team and prepared to move my effects to Mexico. During my stay at home, it being election time of year, both in State and in nation, property would not sell, so I was compelled to leave my home and land. At this time William McKinley was president of the United States. He was succeeded by Teddy Roosevelt.

Having got a small company together, we left Payson on the 19th of November, 1900, for our new home. Went on the Union Pacific to Denver, then on the Santa Fe to El Paso where we arrived on the morning of the 26th. We were delayed 3 weeks in all for the papers of some of the company, during which time the smallpox broke out in a company who came a week ahead of us, but who were also detained, so upon our arriving in Dublan, on account of false report of our exposure, we, my whole company of 51 souls, were placed in quarantine for 15 days. We were treated in a very friendly manner, but on being released, we journeyed home, arriving January 17th, two days less than one year from the time we, the pioneers, arrived a year before in Old Mexico.

Antha with her her several children moved into the log house. Annie with her five moved into the tent which leaked badly from the heavy storms that came in the rainy season. We dipped out the water with cans as fast as it flooded the floor of the tent, and during some of the terrible sandstorms that struck us, the family had to forcibly hold the tent to the ground to keep it from blowing away. All the elements seemed to be untamed. The dust storms were so thick for three days at a time you couldn’t see across the street, and when the sun shone, it burned like an oven.

While living here, Ruth was born, and Lula had typhoid fever. She lost all her hair and her ability to walk.

Lorenzo built another room or two on the log house which became the town post office. He was postmaster, assisted by Alfred. They carried mail to and from El Tigre, Pilares and Fronteras, the train terminal. Lorenzo liked to shoot wild duck and deer, so he always carried his gun with him.

On one of these trips, as he was going along the trail, returning to Pilares with the mail sacks tied to the back of his saddle, he saw bear tracks in the sand. He followed them for awhile and then they disappeared near a wash with a few scattered trees. A tree was a welcome sight in this dry and thirsty land. He pulled up his horse under one of them and got off to rest himself in the shade. Suddenly he heard a loud “gerr-uff!” Among the branches. He glanced up and saw the lost bear ready to pounce down upon him. He made a dash for his horse, swung into the saddle and grabbed his gun and fired. The bear fell wounded and angry. He growled and bit as his wound. Lorenzo prepared to run should the bear give chase, and placed another shot. “Old Cinnamon Bruin” fell, mortally wounded.

Lorenzo came into town, got a wagon and some men went to help load the bear and bring him home. The town folks all came in to see it, and we all tasted roast bear meat. Lorenzo used the bear fat to polish the harnesses and saddles of his horses. The Van Luvenses perfumed some of it and used it for hair oil for a long time, and some used it for hand lotion.

In 1901 President Ivins came over to install Orson P. Brown as first Bishop of Morelos, with Alexander Jameson and Lorenzo S. Huish as Counselors. The Bishopric had many and varied problems to solve, many which made Lorenzo scratch his head, which he always did when thinking or disturbed. In this particular case it was a woman caught in sin. No one knew the extent of the offense, but there was the second fatherless baby. It was suggested that she be cut off from the Church. Lorenzo pleaded leniency. The girl needed teaching, he said, and to cut her off might force her to sink lower than she was. He was understanding of the weaknesses of humanity. Leniency was finally granted. The woman married a man in the Church and reared 10 children. She was always grateful to Lorenzo for giving her another chance.

On Saturdays every head of a family was expected to donate that day in public work, such as working on the meeting house.

The first school started in 1901 in the schoolhouse. Alexander Jameson and Percis Maxham were the first teachers. Later came Lottie Webb and her daughter Estelle, Nelle Spilsbury, T.R. Condie, Newell K. Young and many others. Lorenzo had children in practically every class in every year.

About 1903 Lorenzo bought a ten acre farm south of the Bavispe River. Here Annie moved from the tent into a large brick one-room house. Here Edna was born. She became very sick, and we feared the worst. Lorenzo was called to bless the baby. He went outside, poured out his heart in prayer and asked the Lord that if the baby was to live that He would let her smile at him. When he came to her sick bed as he was about to lay his hands on Edna’s head, she opened her eyes and smiled.

In two years Lorenzo had the fruit trees growing, a large peanut crop, huge sweet potatoes, and watermelons too big to carry. He said he had never seen such fertile soil. We had the largest tomatoes. It looked as if the phantom “want” had been licked for good. Lorenzo also ran a small general merchandise store in town.

In November, 1905, Lorenzo and the older boys had gone to Dublan to buy merchandise. The rainy season had been torrential. The Bavispe River began to overflow its banks and was soon surrounding the brick house. Annie was all alone with the little children. The boiling flood shut her off from town. There was nothing to do but pray that someone would remember her and save her family from being washed along with the muddy mass of water.

The Spirit of the Lord moved upon the Snarr boys, and they came and hauled her out. The water was way up to the sides of the horses. A messenger was sent to Lorenzo to tell him his farm was nothing but a sandy river bottom. He had gone as far as the “Cane Brakes” between Oaxaca and Morelos on his return trip. His first question was, “Where is my family?” According to his calculations that “roaring monster” would hit his farm in the night time and his family would be swept away without warning. On finding they were safe, he sang: “Providence Over All.”

The following six years Annie lived in the back of the store. Here she gave birth to David, Lena, and Alma, while she helped with the clerking and made molasses cookies and other articles for sale.

In 1906 advance word was sent to Morelos for the people to be on the lookout for a bandit by the name of Narcross and his companion, who were fleeing from Chihuahua westward, followed by Mexican officials.

One morning soon after opening the store, a strange acting man came in. He was restless, bought a piece of salt pork, then went to the door and looked north toward the foothills. He then bought some sugar and other supplies, every few seconds going over to the window or door and looking out. What we did not know was that there was another man on a horse ready to give the signal should their pursuers be spied. Suddenly and without a warning, the Morelos police appeared at the north door and shouted, “Hands up!” Mother called Lula to take the baby and run for safety which she did. Narcross grabbed for his own gun, as he dashed toward the door, pushing aside the guns of the officers. As he began to run, Sam Jarvis fired a shot, and the bandit fell with a thump in our front yard. The swift bullet just scathed Lula as she ran for safety to Antha’s. The people gathered around. Narcross, still alive, asked for a smoke. They folded an old burlap sack and put it under his head. The blood flowed from the wound. The man on the hill disappeared and was not heard of more. While John McNiel was sending word of the capture to Fronteras, Narcross died.

Lorenzo had many interests. He stared an apiary, a colony of bees. He made a picturesque sight in his veiled bee hat and gloves, with his hand bellows, smoking the fighting bees as he took out slot after slot of honey to be uncapped with a hot spatula, put in the honey extractor, and whirled around until every little cell was empty and returned to the hive to receive a refill of sweets from the catclaw and mesquite trees which bloomed everywhere in profusion. Sometimes he would cut out large chunks of honey in the comb, a delicacy for our table.

Morelos boasted of one midwife—Grandma Lillywhite, who brought the babies—but Lorenzo was the town’s practical doctor for many years. Moroni Fenn claims Lorenzo saved his leg. He accidently shot himself in the knee. Lorenzo removed the bullet and cared for the wound until it healed. One day his son Jesse came to him from poking corn down in the grinding mill where his hand caught in the cogs, taking his little finger off, all but the skin and enough flesh to keep it dangling. He came to father, carrying his finger in the unhurt hand. Lorenzo replaced the finger and sewed it on. It’s still there after 73 years. When Willard had his had crushed in the hay pulley and Emma got her finger split in the honey extractor, Lorenzo doctored them all without fatalities. He used iodoform for a disinfectant. He made veratrum for fever, burnt alum for proud flesh, and calomel for a laxative. He also made an eye water for sore eyes. These with many remedies the housewife devised, such as catnip for babies, onion syrup for a cough, one teaspoon of coal lamp oil for cramp, castor oil for summer complaint, mustard plaster for inflammation, sweat baths for la grippe, sulfur and molasses to purify the blood, etc., usually brought us through, while we traveled through mumps measles, diphtheria, pneumonia, typhoid, whooping cough, infantile paralysis, and what have you.

Lorenzo carried on his blacksmithing, shoeing his own horses, and later with a bellows, anvil and sledgehammer, turn the red-hot iron into most anything he wanted.

He was a builder and carpenter, also built a brick kiln where he burned the small adobes until they turned a beautiful red brick. He was partners in a threshing machine. He cobbled our shoes, pulled teeth, and cut the boys hair.

He freighted most of his merchandise from Douglas, Arizona on the border, lodging at night with Mr. Boyington in Agua Prieta who lived near the old historic bullpen.

But reverses seemed to dog at Lorenzo’s heels. He trusted out his merchandise to those with a hard luck story and soon the store doors had to be closed. He invested in property along the lower Batepito. It was the Jackal Flat where Old Thomas, a Mexican, lived and reared his family in the little hut. Here he put a purebred stallion, and when they found him headfirst at the bottom of an old dry well. Undaunted, he planted roses along the ditch banks and called the place “Rosebud Flat.”

I love to remember him best on holidays: 16 September or Cinco de Mayo. The red, white and green flag was raised before dawn. Lorenzo S. Huish was marshal of the of the day. He would lead the parade, dressed in his best with a cocked hat with a feather in it, riding his steed, all curried for the occasion. We shouted, “Viva Mexico!” and “Viva Porfirio Diaz!” and Lorenzo’s daughters sang, “Mexicanos, al grito de Guerra,” which is El Himno Nacional. All the younger children braided the maypole or gave a flag March, and we drank lemonade made of tartaric acid, lemon extract and sugar. In the afternoon, Lorenzo umpired the ballgame. I can hear him grown now when the batter made a bad play. Then in the evening came the grand ball, and everybody was there in their starched clothes and shoes polished with soot and vinegar, ”raring to go!” Lorenzo called the dances to the tune of “Turkey in the Straw” or “The Irish Washerwoman.” He danced while he called, and often led the grand march himself.

In 1901 Petrilla died in childbirth. It was a great sorrow in our family. Ruby said it this way: “I had seen father in many moods-laughing, singing and suffering, but only once or twice in my life did I hear him cry. One of those times is when Pet died. He came into the house and threw himself on the bed and wept. It was not like I cry, but something very awful, like the groaning of the soul, and it frightened me.” Surely only one who loved tenderly could weep so bitterly. I remember they placed a handkerchief in her hand as they laid her way.

Morales boasted a two-story schoolhouse and church house now, near the little knoll where Apostle Teasdale had prophesied a temple would be built. Gladys recalls how his countenance changed as he made the prediction one day in church.

A Mexican Revolution was pending. Blanco was the leader of the rebels. The final crisis came in August 1912 when he heard Salazar was headed for Morelos.

On the last Sunday in August, the Saints met for the last time in public assembly. It was a sad meeting and many tears were shed, but the next morning the wagons began streaming toward the border. All the hopes and accumulations of 12 years were hidden in the ground or packed into a wagon. In our wagon we had to have a pair that springs his mother was at the critical period of life and had to lie down.

Salazar and Rojas arrived early in September. They destroyed the houses, killed cattle and wrought havoc everywhere. Near Douglas, Arizona, we moved into a tent provided by the U.S. government, with bacon, flour, and other provisions, until we could find employment or homes elsewhere.

Lorenzo decided to settle in Douglas and purchased some property on Railroad Avenue. Here he built some flats for rent and started merchandising again in the grocery business.

Antha lived near the story in back. While tearing down some old buildings for reconstruction, Willard caught smallpox. Mother cared for him and was soon to succumb. Both of them were isolated in the Pest House southwest of Douglas. The disease went hard with them, and Lorenzo often went out in the backyard, where he knelt down in humble supplication to the Lord to spare the lives of his loved ones. He called this place is sanctuary.

No sooner was Willard out of the Pest House than Lorenzo was in. The only comfort he had was now he knew how Job suffered when he was covered with boils. And he, like Job, new again, that his Redeemer lived.

Again the business was not too successful and finally closed doors. Another “slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip,” as Lorenzo used to say.

Lorenzo never ceased his missionary efforts. One time he was visiting Henry Johnson who worked with Mr. Donahoe in real estate. One day he said, “Henry, if you die first, I’ll preach your funeral sermon, and if I die first, you preach mine.” He said, “No, Mr. Huish, but if you die first, I’ll place a red rose in your hand.” And so it was.

Lorenzo had been a baseball fan ever since he organized the first team in Payson. Once the ball hit him in the temple cutting a nasty gash. He was helped from the field his blood gushed from the wound. The scar stayed for life as did his love of the game.

He spent part of his later years working in the temples. He did over 100 names of his ancestors. His own family was sealed to Apostle Heber C Kimball, a popular procedure in the Church of the time.

As Lorenzo’s hair whitened and his complexion reddened, and his step grew a little heavier, he sat in the big chair on the porch a little more. And he lived even more in the “Holy Land” a song: “Sing me the songs I delighted to hear, Long, Long ago, Long ago.” “The old wooden rocker so stately and tall” still stood in the corner of his memory, and “Grandfather’s Clock” continued to tick away the seconds of his life. “In the Gloaming, Oh My Darling,” he sang over and over again. “Tis the Last Rose of Summer, left blooming alone all her lovely companions are faded and gone.” “And who would inherit this bleak world alone?” He and his baby brother Fred were the only ones left now, and he thought much of the time “when they’d meet ne’er to part, and would fall on each other’s necks and kiss each other,“ “In the Heavenly Songs of the Heart.”

Then he would come into the kitchen and seeing, “Darling I am growing old. Life is fading fast away.” In this he continued in retrospect, he sang with more feeling, “And now we are aged and grayed, Maggie, the trials of life nearly done. Let us sing of the days that are gone, Maggie, when you and I were young.” Now he was 82, still had his teeth and hair, eyesight, and his health. He said it was because he had always kept the Word of Wisdom, and up until now he had been able to walk two miles to pay his tithing at the Haymore Mercantile. But his life had been a full life, for he was like Joseph of old, yet live to trot his children, and his children’s children, to the third and fourth generations on his knee. One day he called at our home to give the children a lump of candy or a few kernels of popcorn out of the pocket of his heavy gray sweater, and incidentally to talk of something he had been reading. He loved to visit. I said, “Father, I can’t understand how you can speak of death so calmly.” He commented, “When one gets to this age of life, things don’t look the same as it does when you are young. Each day is just another step toward an open door ‘where eye hath not seen, nor ear heard the things which God hath prepared.”

At the recommendation of President Ivins, Lorenzo made a trip to the Salt Lake Temple to get his second anointing’s. This was a crowning blessing of his life.

Some months before he died, his eyes dimmed. One day I went to see him as he hadn’t been feeling too well. He looked toward Emma and said, “Who is this?” and Antha said, “Why, don’t you know Emma?” and he said apologetically, “Why, of course.” Soon I got ready to leave, and as I told him good night he said “Daughter, always be true to the Gospel of Jesus Christ.”

Not too long after, he got worse. He suffered with cerebral hemorrhages. One cold night he fell on the porch. Mother came to his rescue in her nightgown, as she had retired for the night. She lugged him into the house at the expense of her own health. She caught a severe cold which ended in intestinal flu.

On January 3, 1937, I saw the look of death on her face and ran over to tell Antha and father. They brought father over in a chair, and for some time he just sat and looked at her, then he took her hand. There was no sign of recognition. Then a voice trembling with the motion, he said, “Annie, don’t you know Ren?” But she was gone. They had weathered life’s storms together for 52 years. Father followed her in August of the same year.

We followed him to Porter & Ames mortuary where he lay in peace, a brow as serene as the morning, with a red rose in his hand.

Adapted by Franklin D. Haymore from Emma Huish Haymore (comp.) The Story of Lorenzo Snow Huish (Mesa, Arizona, 1962)

Stalwart’s South of the Border, by Nelle Spilsbury Hatch pg 273