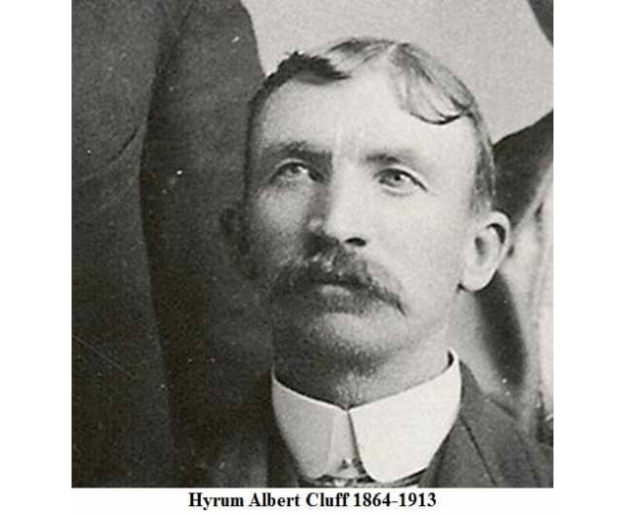

Hyrum Albert Cluff

Hyrum Albert Cluff

(1866 – 1913)

I was born in Provo City, Utah, October 26, 1866, and was baptized when I was eight years old by David Jones. I was confirmed by Henry Rogers.

My father, Moses Cluff, moved to Arizona in 1877 in Apache County, to Show Low. We cleared off the pine timber and fenced our farm, built large houses and ground are corn in hammer mills. For nearly 2 years, I herded cattle for Mr. Cooley with the Apache Indians, during the summers. In the year 1878, we moved to Forest Dale.

In 1879 my father went to Provo, Utah. My mother, Jane Margia Johnson Cluff, and the family moved to Arizona. My oldest sister got married that winter to James Clark Owens. Then my mother moved to Woodruff on the Little Colorado, and my father moved to the Gila River in Arizona, Graham County.

I worked on the Woodruff dam and bought me a span of horses, then worked on the railroad and bought mother of rock house in the Woodruff Fort.

In 1881 the Woodruff dam went out and I helped put it in again. In September 1882, I worked for J. C. Owens putting up hay and in October 1882, mother and I moved to the Gila in Graham County, Arizona, where my father was. There was quite a settlement and lots of mesquite brush all over the town and you could hardly see from house to house…

Mother and I went back to Woodruff on a visit. Mother stayed there and I came back and helped father on the farm. Mother took sick, and sent for me. I started for Woodruff in January, 1885 and came back in March, the same year, with William Rollans. We were nearly killed by Apache Indians. We camped on Turkey Creek, 10 miles from an Apache camp and the Indians danced and sang all night. We traveled down the Black River, which was running very high and we nearly drowned. The next day, the tongue of the wagon broke and when we stopped to fix it, an Indian road up and told us to follow him and to hurry. He seemed very uneasy. He led and we followed as we thought the other Indians were after us. The next day a party of white men passed on the road and told us that two of their group had been killed the day before and to keep our eyes open for Apaches…

In May, 1885, I met and started going with Rhoda Haws and hired to William Hunly to drive a team. In March 1886, I heard George M. Haws and worked and bought me a farm. I planted some corn and made adobes through the summer. My mother came from Woodruff that summer with brother Combs and Rhoda and I went to meet them. On September 5, George M. Haws ordained me an Elder in the Church and later that day, Rhoda and I were married. On September 6, 1886, the day after our wedding, Rhoda and I started for St. George…

The first night out, we camp at Thomas, Arizona. When we got to Black River, it was up quite high I crawled across in a big rope and got the boat on the other side. When we sent across the wagons, the women had to stand on the spring seats to keep them from getting wet. Brother Matice’s wagon tipped over, but we got it out of the river in one piece. We camped in Seven Mile Canyon and that night we had a dance on the ground around the campfire. From Seven Mile Canyon, we traveled to Woodruff. We stayed there for two days and had a good visit with my sister and her husband, J.C. Owens. We went on to Saint Joseph on the Little Colorado. We stayed at Brother Porter’s and had a dance. Then Rhoda, James Cluff and his wife went on and left the rest of us. They traveled to Black Falls where we caught up with them and traveled together to the Willow Springs.

When we got to the Colorado, it was up and Brother Johnson was herding a big herd of cattle over for Brother John Wiley. We had to take wagons all part and ferry them over in pieces but we got across all right. We arrived in Kanab and had a dance. We stayed there for three days and found one of our cousins there and then went to Long Valley where we stayed two weeks with Brother Warner Porter. They had lots of fruit which was quite a treat. We also saw G[eorge] M. Haws, Rhoda’s brother and his wife. We went on to St. George and went through the temple on October 26, 1886, and saw and heard many great things which we will never forget. There we were sealed for time and all eternity by Brother McCallister. We then went to Washington, six miles from St. George. We stayed there all night and then started for Provo. It was a nice trip, but cold. We arrived in Provo on November 10th. We stopped at James Meldrum’s, Rhoda’s sister’s husband. We stayed with them all winter I hauled wood out of the mountain and frosted my feet that winter…

In May, 1890, I took my wife, her mother and two sisters and started from Mexico. We had a very dry trip. We got to the Animas Valley, horses got alkalied and the water made all the sick. We arrived in Colonia Diaz Sunday morning on June 6th. We got the Colonia Juarez on Friday the 11th and to Colonia Pacheco Sunday the 13th. We found Brother Haws and his family all well. Brother Haws went to Round Valley and I thought that it was the prettiest place I had ever seen.

We stayed at Pacheco and spend the Fourth of July there. Started back to Central and arrived there on 23rd of July. It was an awful muddy trip. The 24th of July we celebrated with the community.

I freighted from August to March of next year between Wilcox and Globe City, Arizona. On August 19, 1890, I started from Mexico. When I arrived at the Custom House at Senicone (Asencion), I had to give the $50 bond before they would let me pass. Bring your troubles went with me to look over the country around Colonia Garcia. Peter McBride, John Hill, George Haws and me went Round Valley to look for land for a farm but gave it up. I settled in Corrales, build the house and fenced me a lot.

The following spring was very dry and we had to live on cornbread. Brother James Sellers and I built a dam the creek and got irrigation water to our land. On October 20, 1892, I went to Colonia Juarez to make brick for George Haws. I went to Colonia Diaz in November to get some cattle from Hendricks. Arrived in Corrales with the cattle December 6th. On Christmas I was the clown and George Hardy was Santa Claus. While he was taking the presents off the tree, the cotton on his suit caught fire from the candles and he was burned quite badly. It was an awful experience…

In September, 1893, I was out hunting my horses and ran across a bear. I took out my lasso and caught him by the neck and pulled him out of a tree. The commotion frightened my horse and he threw me off. Somehow, I managed to hang on to the rope. The bear must have been as scared as I was because instead of attacking me, he tried to climb back up the tree. When he got up to fork in the tree, I let the rope go slack. The bear, caught off balance, fell headfirst through the fork in the tree and yanked the rope tight, he hanged himself as he was unable to touch the ground.

On the first of October we were counseled to move back into town because some Indians were acting up. We moved closer to Corrales and lived in a log house. The next February, we moved out to the ranch….

I also helped cut the road from Pacheco to Round Valley. Moved to Round Valley December 8, 1894 and cut logs and put a log house up. We moved into our new house on January 14, 1895 and had a dance. I plastered the house in April and helped survey the graveyard in Garcia.

Saturday, June 9th, Rhoda was not feeling well, so I didn’t go to meeting. Sister Phoebe J. Allred anointed Rhoda and confirmed the anointing. On June 10, 1895, at 1:00 a.m., Fernie Jane Cluff was born. Annie D. Farnsworth came in and helped us with household chores.

On July 24, 1895, we had a celebration here. People came from Pacheco, Cave and Juarez. We played ball, had a picnic and in the evening, we put on a very good program. I took the part of the nigger…

In November, I wanted cattle drive to Juarez. We camped out one night in Corrales. That night the cattle stampeded. When we got to the corral we found that they had mashed the log corral fence down and some of them were under the big logs. We stayed up all night to put the corral backup and at daybreak went out to look for the cattle that had stampeded. Rhoda met me at Pacheco and went on to In November, I went on a cattle drive to Juarez with me. The last of the month, I dug potatoes and went out hunting. I got four big gobblers. Rhoda put her carpet down the 29th…

On August 22, 1896, we went to Juarez to conference. We heard some very good instruction, but Fernie, the baby, took sick and we had to come home. She kept getting worse. She passed away on September 12, 1896 at 6:00 a.m. The funeral services were held at my house at 10:00 a.m. and called to order by Elder J[ohn] T. Whetten. We sang “Come Let Us Anew Our Journey.” The prayer was by Frank Shafer and we sang “Weep Not for Her That’s Dead And Gone.” A.L. Farnsworth spoke for some time and gave some very good remarks. Then Brother J. T. Whetten spoke a short time, and read some nice verses composed by Mary Farnsworth. They we sang “Farewell All Earthly Honors.” We then went to the graveyard and paid the last respects. The dedicatory prayer was by Brother Farnsworth…

In July 1898, we moved to the sawmill where Rhoda cooked for the mill hands and I worked with the logging. I took her from there with me up to work on the wagon road at Soldier Canyon. I was the road overseer. From there, we went home in November.

The spring of 1899 was very cold. I was called by the Bishop to take a man from New York up to inspect the timber of the nearby country. He was with a railroad company who was anticipating building a railroad near here…

July 24,1900, we held a celebration representing the Pioneers reaching Utah. We had Indians camped on the square. We put up a liberty pole and I was the first one to climb it.

On August 3rd, we were visited by Joseph F. Smith, Second Counselor to the President of the Church. He brought with him, Brother Seymour B. Young, the First President of the Seventies.

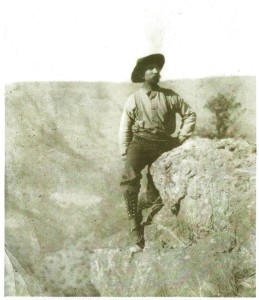

On September 12, 1900 Benjamin Cluff, President of the Brigham Young Academy, visited us. He was traveling with a party from the Academy, on their way to South America. They stayed in Garcia one week and excavated some ruins and got some specimens. I traveled 75 miles south with the expedition as guide. On returning home, I met a couple of outlaws. They drew their guns on me and held me a prisoner for several hours. They finally decided to let me go and I gratefully returned home in one piece.

I cut the oats for the people here in Garcia with a self-binder. Went out hunting and trapping. Got two big lions and two wolves. When I returned home, Apostle A[braham} O. Woodruff and President Ivins were there at Garcia. They held meetings and then went on to Chuhuichupa where they organized a ward. G{eorge] M. Haws, Rhoda’s brother, was appointed Bishop. After the conference held at Juarez, Thomas Allen and Brother Harris followed some Indians who had been stealing corn and potatoes. They ran onto their camp and killed two of them. Brother Ivins and Woodruff helped bury the Indians. Bishop Whetten sent a runner out to Chuhuichupa to warn the people and another to Juarez to take the report to get ammunition for the protection of the ward…

February 23rd, Rhody and Josephine Haws, my sister, started to Gila Valley for a visit. I am getting along fine. There is now plenty of water thanks to the dam we put in. The ground is in fine condition for plowing and every one is preparing to put in big crops this year.

March 9th, got a letter from my wife, Rhoda. She and the children arrived in Pima alright. I went to Juarez after Dr. Shipp who came to operate on Sister Ida Whetten. She took a baby from her. I rode all night and it snowed and rained on me most of the way. I caught cold in my eyes and I have been housed up doctoring them and it seems so lonesome here alone without Rhody and the children. This is the first time that Rhoda and I have been away from each other for any length of time since we were married.

June 3rd, the country is on fire and the valley is full of smoke.

Brother Taylor of Juarez sent for me to come down and trap some bear in his pastures. They are killing off his cattle. July 2nd, trapped one week and caught three bears and while I was there, Rhoda and the children arrived from Pima. I was glad to see them again. The baby looked quite bad.

August 23rd, got a letter from a Dr. Hughs of Philadelphia. He wanted me to go out with him as a guide on a hunting and trapping trip. He came with a party of friends and we killed several lions, grey wolves, foxes, turkey, and deer. I took them down to Casas Grandes station and they returned from there back to Philadelphia apparently well satisfied with their trip to the wilds of Mexico.

While I was out with Dr. Hughs, I took him to the old ruins 15 miles on the west side of Garcia Valley. We excavated some ruins and found one skeleton. Many thoughts passed through my mind while working on these ruins and reflecting on the people who built those houses.

October 22nd, me and Mr. Barker and Ernest Stiner started out trapping. We went south-east from Garcia on the Rio Almais. We were gone six weeks. We caught and killed five bears, eight lions, eleven turkeys, and several deer. The last bear we killed pretty near got Ernest and myself. It was a large silver tip bear and he came within ten feet of us with his mouth open and had it not been for the dogs, he would have gotten both of us…

September 10th, I went to Juarez and took my family and then went on to El Paso. I took Matilda and Lorena and Sister Haws with me to El Paso. We returned home from there and I brought a hunting party in. When we were between Casas Grandes and Juarez, I got on a mule and it jumped in a hole and fell. I got my foot caught in the stirrup and the mule dragged and kicked me until finally the stirrup broke and I got loose. I was badly banged up and the backs of my legs and my back were black and blue. I didn’t have any broken bones though and was able to take the hunting party to the Blue Mountains.

November 22nd, I took another hunting party from Kansas on a trip. We sow one lion but didn’t get anything. I also showed them some ancient buildings.

December 25th, the band serenaded the town. It was a very enjoyable holiday.

February 8th, was permitted to accept the high laws of God which was a very great trial to Rhoda. The Lord has blessed us a great deal and I’m sure everything will work out. I married Delia Floretta Humphrey here in Garcia, Mexico. The year is 1903.

April 1st, I took a gentleman by the name of R. C. Cross of New York out on a hunt. We visited the ruins at Cave Valley. I took the folks out to Peacock after my traps and camped. Rhody and I went into a very deep canyon and ate dinner. I took her picture twice. That day as we came over some very rough places, Rhody very nearly fell off her horse. She went with me to hunt bear that had been gone with my trap for six days. We were in some rough country but we found the bear dead and then found the trap on our way back to camp. I killed three deer and took the picture of Rhoda’s horse and deer.

October 2nd, Floretta went to Juarez to put up fruit for us. I got a letter from her.

January 1, 1904, the weather is very cold and windy. The people seem to be getting careless and there is neglectful spirit among them. I received word that my brother, James Cluff, was cut off from the church for adultery. We put a drop curtain in our meeting house. It cost $36…

March 7, 1904, this morning at 11:00 a.m. our first son was born to Rhoda and I. He is our 9th child. He weighed nine and a half pounds. We are so proud of him and all the neighbors has been in to see him and congratulate us. We have named him Hyrum Albert Cluff.

April 3rd, we took our boy to the meeting house and had him blessed. The measles are raging here. There are 44 cases here in the Garcia Ward. So far there have been no deaths.

April 15th, 1904, the measles are still raging. Rhoda is sick with them and five of the children are down with them. We were called upon to give up our dear baby boy. He only stayed with us one month and four days. It is so hard to part with him because he is the only boy we have ever had. I had to leave Rhoda and take him up to the cemetery. She was sick and in bed with the other four children. I am so sorry she could not at least see our sweet baby buried. There were only two wagons, but there was quite a large crowd. Elder Clark of Dublan offered the dedicatory prayer. The ward choir sang “Your Sweet Little Rose.” Bishop Whetten offered prayer and we returned home.

April 16th, the children and Rhoda were awful sick again last night. It is a very gloomy time for all of us but we feel to say in our hears that the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away, blessed be the name of the Lord.

Sunday, April 24th, the family and I went to Bishop Whetten’s for dinner. Most of the people are getting over the measles.

August 25th, there was a large flood that came down the creek here and washed out some fences. Also the river at Hop Valley was up and washed out lots of the logs and ties which we cut for the railroad. I was rolling logs and wading in the river until 12:00 last night. Sister Haws and her daughter came here from the Gila Valley to visit. Rhoda was glad to see her mother and sister. Her mother is getting quite gray. They visited in Chupa [Chuhuichupa] and then came back here.

October 12th, I took all of my folks and went to Cave Valley with Rhoda’s mother and sister and some of their brothers from Pacheco. We had a good time and then they went back to the Gila Valley.

Sunday, October 23rd, we had a good meeting. Spoke on the order of the marriage covenant. I am still shocking my corn.

October 26th, this is my birthday Rhoda gave me a nice liver righ for a present. My aunt’s father’s fist wife was here on her way to Chup. She came on a visit from the Gila Valley.

October 31st, Bishop Whetten’s wife is very ill. It seems that her life hangs on a thread. I just got a letter telling me that my brother John’s wife passed away. She and the baby were buried together.

November 31st, Bishop Whetten’s second wife, Emma died today. She was sick and almost a solid sore from head to foot, but it healed up before she died.

December 25th, Christmas. Rhoda and I and two of the children went to Juarez and bought flour and apples and toys for Christmas. We had a community program and played all kinds of games. At night we had a dress party. Rhody and I represented George Washington and his wife Martha. Floretta represented the flower girl and Tillie represented Little Bo-Peep. Rhody and I won the prize.

January 2, 1905, just settled my tithing for the year, 1904. The amount was $100.25. My brother Brigham Cluff is here from Pima, Arizona, also George Haws, Jr. The Relief Society got up a big party to get money for the purpose of getting burial clothes for people. It is a hard matter to get clothing on such occasions as we are 50 miles from any railroad and 35 miles to where they can buy much from the stores. The stores here are small and don’t keep much supplies.

February 14th, I took a load of lumber to Juarez. I saw Apostle Teasdale and he blessed me. I have started up a trade and am trying to handle produce for the people.

March 20th, there has been some talk and discussion on the God Head and I was called to make a special visit to all the people who had advocated that doctrine that Adam is God and the Father of Christ. We were told to tell them that this doctrine is definitely false. Today in meeting all were given one week probation and if they didn’t repent they would be dropped from their positons in the ward…

September 14th, went to Colonia Juarez to conference at the Stake Academy. As President [Joseph F.} Smith and party entered the building the congregation stood and sang, “We Thank Thee O God for a Prophet.” President Jarvis opened the conference and spoke of the growth of the people and stated that this was one of the greatest days that the people had enjoyed in this land by the presence of President Smith. He mentioned that it also was the national day of Mexico. I attended 11 meetings at the conference and all our children shook and with President Smith at Sunday School. Two thousand two hundred seventy-two souls attended the conference. President Smith told me to go and be baptized for my dead father.

Floretta came up to stay with us for awhile. On September 4, 1905 she gave birth to a boy at a quarter to seven o’clock in the morning. We named him Charles G. Cluff. It is her first child.

December 2nd, there has been lots of rain and the river has been up quite high. The river washed lots of fence away at Corrales and took 4 houses out of Colonia Juarez, 8 in Colonia Diaz, 33 in Sonora and left the people without anything only the clothes they were wearing at the time. Their household goods all were lost in the flood but through the blessings of the Lord, there was not one life lost. The people of the Stake has made up a fund for the homeless.

My tithing for the year 1905 was $74.50.

March 3rd, we have got the telephone poles up through our town and it will only be a matter of time when the telephone will be in all of the homes of the ward in this stake. It will be a blessing to all of us.

April 2nd, had been out on the mountain hauling logs for H.H. James’ sawmill. Art Farnsworth came over to tell me that the baby, Alberta, was sick. I went home and arrived there at 4:00 in the morning. I found her quite sick. Friday night at 9:00, she passed away. She was a sweet little girl and she brought sunshine into our home with little time she was with us. The people here have been very kind to us and in all they can for our dear little pet. She was such a sweet baby. There seems to be so much sickness in the ward now.

September 24th, Rhoda and I are preparing to start for Salt Lake City this morning to do temple work.

February 26th, the Garcia sawmill blew up, killing George Turley and injuring Art Farnsworth and Sumner O’Donnal quite bad. The money panic which was raging in Utah and Arizona has struck us here and times sure are hard.

May 15, 1908, our 12th child and third son was born to Rhoda. We named him William Templeton Cluff.

June 5, 1908, Apostle Anthony W. Ivins and our stake presidency called a special meeting here in Garcia. There had been some differences and trouble in the order, but after the brethren were called together and matters were properly adjusted, there was a general hand-shaking all around and a good spirit prevailed. I was called his second counselor to Bishop J[ohn] T. Whetten of Garcia Ward and was set apart in ordained a High Priest…

June 19, 1909, Floretta had a baby girl. We named her Violet.

July 5, 1909, I planted corn on my lots. Times are very hard and the Bishop is letting the people have the tithing corn to eat…

February 2, 1910, a comet appeared in the western skies. June 16, almost all men Garcia are up in the mountains working on the railroad. I came home to check on things and found the farm is looking good. Those are staying here have planted all the farmland in the Valley in grain, mostly oats. There are quite a lot of apples, peaches, plums, charities and a number of kinds of small fruit being raised here this year.

June 22, 1910, Rhoda had another boy which makes 13 children. We named him Harold Alton Cluff. Rhoda and the baby are getting along fine.

October, the rebels here took it up against the government. It has caused great excitement among the people, but they seem to be peaceable towards the Latter-day Saints. The Church President, Joseph F. Smith, sent Apostle Ivins to assist the people here and he was the means of getting guns and ammunition in for the Mormons.

January 19, 1911, it is very cold. Forty rebels came into Garcia and bought supplies in the store and paid for them. They appeared very friendly.

January 24, the outlaws killed Sister Mortenson of Guadalupe and also her brother. The officers caught three of them and one got away. One of the rebels came and stayed all night here in town and said he was on his way to United States the purchase ammunition for the rebels. They have to of a great many of the Mexican soldiers and taken a great many smaller places, but not been able to hold them.

October, when hunting with a party from New York. Madero was the victor of the Revolution and was elected President of Mexico.

December 11th, the railroad is nearly completed above San Diego Canyon. It will be a great benefit to the mountain colonies. The Revolution abated only for a short time. Some of Madero’s generals became jealous of Madero and started another Revolution. Every now and again there is a band of rebels that will ride into town and demand something like food or livestock or ammunition. One bunch numbered 250.

January 1912, the Church sent guns and ammunition to the colonies. The rebels are taking a lot of the colonists’ horses and saddles and are killing off cattle for meat. So far they have not stolen from Garcia…

The people here are getting quite alarmed about the rebel situation. They have attacked quite a few of the Mormons, beating them up with their guns and stolen their horses. Some people have been stopped by rebels on their way to church. They had to sit there in the wagons and watch them unhitch their horses and ride off with them. The rebel generals have gone back on their word to leave the colonies alone. Our men number about 300 and there are about 1,500 rebels in and around this. We are expecting to be called to leave for Pacheco any day now.

July 24th, we held a dance and had quite a good time.

July 28th, we received word to leave our homes. We spent the 29th packing what few things we could take and cooking. We just walked out and close the door and left everything. There were 27 wagons. The men stayed to defend the town and our property but the women and children camped in a lumber shed with very little room. The babies cried all night making sleep impossible for the rest. On August 2nd, Rhoda and the children left for Pima, and arrived the next day.

We men all gathered in Juarez where we decided to hide out in the mountains. I went back to Garcia herd our horses up into the mountains. When I got the horses up to the men, we decided to take them to the border. From El Paso, I went on to be sure Rhoda and the children were all right. On September 20th, some of us went back for as many cattle as we can drive out. October 13th,I arrived in Pima. We put Tillie and Lorena in school in Pima and November 4th, we started for Bluewater, New Mexico. We arrived there the 5th at 1:00 a.m.

November 11th we moved into Nelly Chatman’s house. Tilly went to work at the general store, clerking.

Heber took sick on June 21st and on July 17th, he died.

September 24, 1913, Hyrum* became very sick and was bad from the very first. We couldn’t get a doctor and we just didn’t seem to be able to do anything to help him. He died October 16th and was buried October 17th. His funeral was held at the meeting house in Bluewater. We sang “Come Let Us Anew” after which Brother Tietjen gave the opening prayer. We sang “Oh, My Father” and Brothers Call Hakes, Charley Martineau, Bishop Whetten and Welcome Chapman spoke. We sang “Resurrection Day” and Brother Welcome Champman closed the meeting with prayer. Brother Tietjen dedicated the grave.

We are left alone without a home, no one we know to help us and in a strange new place.

From the journal of Hyrum Albert Cluff, submitted by Mrs. Sarah Matilda Cluff Lewis, daughter.

Stalwarts South of the Border page 113.

*For clarity, the last entry would have been written by someone other than Hyrum as he was the person passing in the entry.