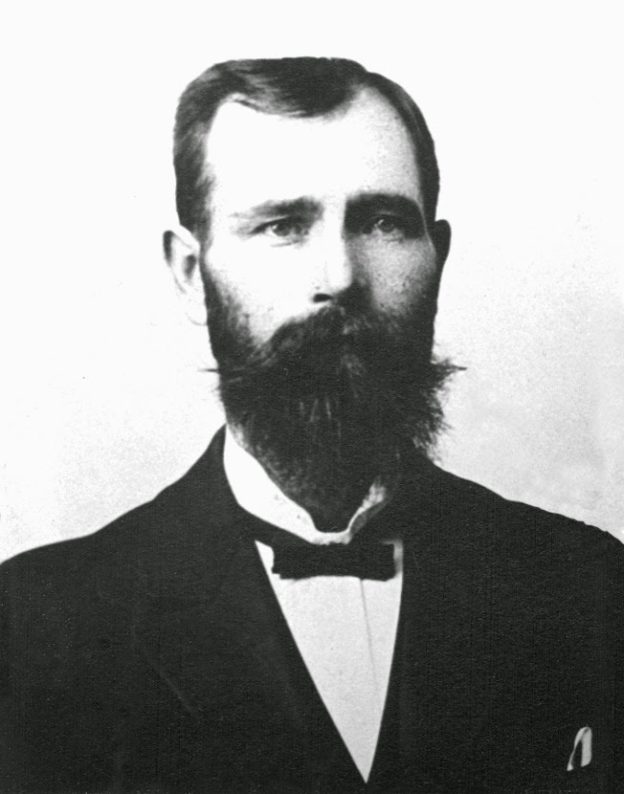

William Carroll McClellan

1828-1916

William Carroll McClellan, son of James and Cynthia Stewart McClellan was born in Bedford County, Tennessee, May 12, 1828. He was the eldest of 12 children, six boys and six girls, all of whom grew to adulthood and married, raising families of their own. Some of them, including Williams, lived to a ripe old age.

William remembered little of the place of his birth as his parents moved to Shelby County, Illinois in the spring of 1833, when he was five years old. There they squatted on a quarter section of land but made no effort to prove it. In 1834, his father bought property from a man named Silver that was already improved with a cabin, smokehouse, and corn crib. This small claim lay in the bend of the Oker or Kaskaskia River, but it was fenced and the land was “broke.” The nearest neighbor was three-fourths of a mile away, but the next nearest was two-and one-half miles distant. Here he spent the following six or seven years of boyhood on the farm, growing corn in the summer, feeding hogs and cattle in the winter, with little chance for education except what his mother could impart of reading and spelling.

His father’s economy and industry soon surrounded the family with the comforts of life. Hogs and cattle sold well and fattened on the range for most of the year. Chicago and St. Louis furnished good markets for all he had to sell.

Under these prosperous conditions the early Mormon Elders found them and taught them the Resorted Gospel. His parents were baptized in 1840. His father, anxious to meet the man through whom the Gospel had been restored, made a trip to Nauvoo, Illinois. He was so pleased with Prophet Joseph and Nauvoo that he bought property in the fast growing city, and returned home determined to sell out and move to Nauvoo. This was not an easy thing to do. Their farm was one of the best and largest in the country, containing 600 acres of cultivated lands. He finally sold it for part cash and the rest stock.

He sent William to Nauvoo early in the spring of 1841 to look after the land he had bought. The party tried hard to reach Nauvoo in time for conference on April 6, but arrived the day after. William was baptized May 12, 1841, when he was 13 years of age. All summer he chored around their Nauvoo property and returned in the fall to help his father move the family onto it.

Trouble then beset them. First to happen after arrival was rheumatism, afflicting both his father and other so terribly that they were confined to their beds for three months. Responsibility for keeping work going both inside and out fell on William, barely 14 years of age. The great herd of stock they had driven from Shelby needed the card of a man, and a strong one, certainly more than a mere lad was able to give. During on of the fierce storm that came with winter, the 60 head struck out of their old home, but the river, full of ice, stopped them. They milled around near the banks until a party took charge and cared for them until spring. Expenses for keeping them cost his father half the heard. Fortunately, tithing on them had already been paid. Shares in the Nauvoo House had also been paid, but loss of his stock, with no way of caring for what he had, taxed his resources. With sickness in the family, bedrock was soon reached. The slide from plenty to poverty seemed but a short step. Making a bare living now rested entirely on William’s young shoulders.

All winter he worked for wages. In fact that was his lot for as long as they lived in Nauvoo. He worked in the brickyard, did team work, and did much boating and rafting. The last two years in Nauvoo were spent mostly on the river where, because he could do a man’s work on the water, he was counted on during all hours of the day, and often did emergency work at night.

Near the last of February, 1846, he was asked by J.D. Hunter to meet him and others at night near the upper stone house. He, Hunter, Charles Hall, Allan Tally, and others with whom he was acquainted, went quietly to Shirt’s lime boat on the bank of the river. Aboard, they pushed into the stream and floated a mile down the river, pulled ashore and put a wagon and team on board. William was told to land at a light he could see on the Iowa side. This was done with few words spoken. Only two men aboard knew who was being ferried, Hunter and the stranger himself. William was curious but asked no questions. This was the beginning of the Exodus.

William stayed several days longer ferrying other parties across. Then he went home to help get his folks ready to leave with a company. First he took his father’s team and wagon, loaded with goods, intending to be gone a month. But instead of being sent back at the end of that time, according to contract, he was sent into Missouri to work for provisions for the camp and was there until May, almost two months. Letters came from his father concerning his lengthened stay, but they were burned. Brigham Young, getting word of the inferred absence, wrote William personally, asking him to go to him at once at Garden Grove. He loaded his wagon with cornmeal and bacon, returned to camp and was soon on his way to Nauvoo, accompanied by three or four boys, who had no teams but wanted to return to their folks.

When they reached Nauvoo, he found his folks getting ready to move from the city. The hostile mobs were making life unendurable. His party was made of his father, mother, and family, Aunt Matilda Parks, T. C. D. Howell, his grandfather Hugh McClellan, Grandmother Rigby, Gabbit and others. They crossed the river at Nashville, as there they gained better teams for ferriage. The weather was hot; they made good time an reached the camp on Mosquito Creek on July 14. William drove his grandfather’s team on the journey.

There was recruiting in the camp enlisting men for service in the Mexican War. William’s father gave him the alternative of enlisting and being part of the 500 Mormons they had asked for or taking care of the four families, as well as the families of his Uncle Howell. William A. Park and James R. Scott were enlisting so William decided to join. He marked off with the 5th Company to camp on Sarapee’s Point. He received his outfit and supplies at Leavenworth and marched on to Santa Fe. From here a party of invalids and laundresses left the detachment and were sent to Pueblo, Colorado. Somewhere on the Rio Grande on November 10, another invalid detachment was sent back to Pueblo. William was sent with this party to care for the sick. It was a long, hard trip. It was terribly cold and four men died; all of them suffered untold hardships, wallowing through the snow, half-clad and half-starved, reaching Pueblo late in December. Here he stayed until the end of May, faring well with supplies from Bent’s Fort, jutting and getting fresh meat every day. When he left, they traveled north, striking the old pioneer trail at Fort Laramie, going up the North Platte. They followed the trail to Salt Lake, arriving July 27, 1847, just three days after Brigham Young and his advance company. There William was mustered out of the army.

On August 29, William, in company with 60 men, 30 of them Battalion men, started east for the Missouri River. They had about six days’ rations per soldier to last them on a journey of 1,000 miles and mostly ox teams to haul them. The first 500 miles there was no game to be found to stretch out their scanty rations. The last half of the journey, buffalo furnished fresh meat for the famished men and even a straight meat diet was better than the starvation days, as they had plenty of salt. They reached camp where William’s parents were the latter part of October, having been absent 14 months. Both his grandparents had died, but all others were well. For a year he worked single-handed, jobbing around Missouri.

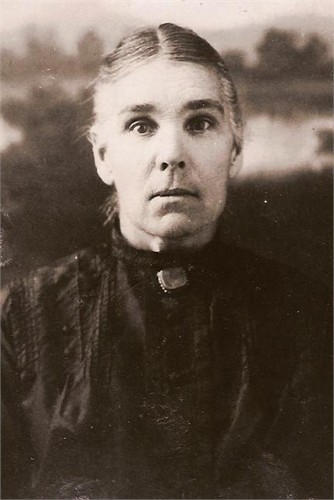

On July 19, 1849, he married Almeda Day. She was his companion until death in 1916, and bore him 12 children in 55 years. She was a daughter of Hugh and Rhoda Ann Nichols Day and was born in Leeds, Upper Canada, November 28, 1831. When she was just a child of four, her parents crossed the St. Lawrence River on ice to New York state where the family probably joined the Church. They sailed by boat through the Great Lakes to Illinois. She buried her mother in Nauvoo. There she met William C. McClellan.

He built a little log cabin and gathered around him enough to make himself and his wife’s family comfortable for the winter. He intended to stay in Missouri to take over his father’s farm when he moved west in the spring, but the gold rush to California had begun and his father and father-in-law urged him to go. He had a baby coming, not much to move with, and was hard to convince; but he began making preparations anyway. He joined his father in putting up a shop for fitting out wagons and other repair work. But before they were ready to work, the gold hunters were on them, wanting supplies of food and shop work done. The next June, 1850, he loaded all he had into a wagon and started west with his father, father-in-law, a month-old baby, and reached Salt Lake City early in October. They passed through a siege of cholera, which cause the death of his brother, and attacked him as well. He settled in Payson, Utah and lived there for 17 years, going through the hazards of land shortage. His pioneering in Utah, the first of three such ventures in the United States, bade his pioneering in Mexico an old story.

In April, 1857, he was ordained President for the 46th Quorum of Seventy. Then the Utah War came and volunteers were called to guard the pass in the mountains, to fortify and block canyon entrances to keep Johnston’s Army from entering and carrying out threats to exterminate a “seditious and disloyal people.” William volunteered and all through 1858 did duty in Echo Canyon. He was called to raise 50 men to help. Because part of the Payson men he needed were already out, he had to go to Spanish Fork for men to fill his company. Captain Kite, Major A. K. Thurber of Springville were part of the 500 men who did spectacular work in Echo Canyon under the direction of Lot Smith. They were instrumental in forcing General Sidney Johnson into winter quarters at Fort Bridger.

In 1863, William’s mother died on April 12, an extreme loss to her family and the community. She was but 52 years old, so her death was a shock. William was then called, in company with others, to meet and help incoming immigrants at Florence, Nebraska. John R. Murdock was captain of this company. His father, his brother Sam, and himself had a private team, probably owned by Jesse Knight, hauling goods for the company. They left Florence on the Missouri about the 4th of July on their return home. The company consisted of about a hundred wagons and four hundred immigrants.

William was set to caring for women and children who had to walk. His job was to keep them ahead of the wagons, instead of straggling behind. William was also camp physician, and kept his medical supplies in his coat pocket.

The Salem Dam near Payson had been washed out four times, taking valuable land with it. In the settlers’ discouragement they turned to him to replace the dam that meant life to their farms. The structure he put in the river is still there, having done service for nearly three-quarters of a century.

In the summer of 1865, Indian trouble began. At first they just acted ugly, but by 1866 they had become mean and hostile and it was necessary to organize for guard duty, keeping men and women in the fields night and day to prevent Indians from even getting near the settlement. Finally an organized army was necessary for the Walker War was in earnest and William, guarding the settlement, was elected May 8, 1866, Colonel of the 1st Regiment, 2nd Brigade, of Goshen, Santaquin, Salem, and Benjamin. This was full time work for seven months for the years 1866 and 1867. There was a little breathing spell during the winter when the Indians could not cross the mountains for the snow. A treaty of peace was concluded in the fall of 1867 and he resumed his work on Payson where he was a member of the town council, serving several terms.

William was the prime instigator in extending the borders of Payson and building a canal from the Spanish Fork River. He kept the work moving, combating the discouragement of those who felt it was too big an undertaking for such a small group of impoverished people. When the work was finally done, “I am prouder of it,” he said in his journal, “than of any job I was ever connect with.” He was also a prime mover in building the meetinghouse, creating the funds as they went along, and in the process a feeling of unity and brotherhood was made that had not existed before. He also built a Relief Society store.

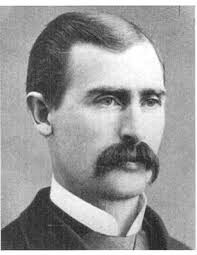

On May 14, 1873, William entered the practice of polygamy by marriage to Elsie Jane Richardson. The next year, 1874, he was induced to go in with a few others and made a dairy farm in Grass Valley, Utah County, Utah, a fertile but cold section of the country in the high valleys of the Wasatch Mountains. Together they farmed a quarter section of farmland and two or three quarters of meadow and pasture land with posts and pole fences. They built houses and outbuildings and put up quite a lot of hay and made excellent cheese. William brought in supplies for this mountain valley project.

Early in the spring of 1877, all Payson and Grass Valley plans were interrupted by a call to go with others to settle in Sunset, Arizona, and help establish the United Order. The call could not have come when prospects for better living were brighter. He had grown children, some of whom were married yet he began preparations to accept the call.

Fitting wagons to carry foodstuffs, seed and implements, and getting teams and livestock to take along was a matter of ease. But sales were finally completed satisfactorily, and he pulled out with four wagons, six teams of oxen, a span of horses, and a light wagon, all filled with flour, merchandise and household goods. A neighbor drove part of his outfit to help him to the first campsite. William left behind a forest of waving hands from neighbors, all of whom wished him good luck in his new venture.

Not far from Payson, he found his neighbor awaiting him with a broken axle. But before he had time to investigate, he heard other wagons following with the Payson band in the lead wagon, ready to burst into a lively tune. Then he knew what was the matter with the “broken axle.” He also knew, again, what warmth the love and respect of good neighbors can mean and what an uplift their interest in his welfare was.

The United Order was Utopian form of living, where there are no rich and no poor, where everyone shares alike. By living the Order, the Saints hoped to become like the people of the City of Enoch, so righteous that they “were taken up and were no more, for God had taken them.” Moses, 7:69). Failing to reach that degree of perfection, they could emulated the Nephites and Lamanites who lived in peace for 200 years after Christ visited this continent, all sharing in common.

Even though the Order, tried by Christ’s Apostles in Jerusalem after His ascension into Heaven, broke up because of weaknesses among its members, and the same failure had come to attempts to establish this Order in modern times, William retaining his hopes that this time it would succeed. He put all his belongings into the Order when he arrived at Sunset, retaining for his family only what the Order stipulated. He hoped only for some of the exaltation that blessings from living the Order righteously could bring. But, after living it for three years and finding that finite men, including himself, were not yet sufficiently perfected, the Order could not be made a success. He left when the Order dissolved with little more than that which the family wore. Worse still he was a disillusioned, discouraged man. For a few years he lived first in one locality then another on the Arizona frontier with little hope of betting his situation until he finally joined a group settling the little town of Pleasanton, New Mexico, a fertile valley near Silver City.

Here a successful and bright future seemed near. But, too soon, fear was added to the remembered disillusionment and discouragement. First, there was fear of Indians. Geronimo and his renegades were on the rampage operating in the area, making fortification necessary for the protection of lives. Second, there was fear of U.S. Marshals who were invading remote frontiers, bent on arresting every man having more than one wife.

Not relishing the idea of a jail sentence and fine, he acted promptly when, via the grapevine, he heard a “place” had been prepared in Mexico. He left at once. With his 16 year old son, Edward, an interpreter and others also seeking the “place,” he left, taking a roundabout way in order to avoid possible encounters with Indians.

They reached La Ascension on February 22, 1885 and with Bate William, who could speak Spanish, they went through the ordeal of customs inspection, a new and bewildering experience. But more bewildering was that no one was there to lead them to the “place,” or to tell them what to do in the meantime. They made camp on little Lake Federico where they shot ducks and fought mosquitoes for two weeks when Alexander F. Macdonald and his party, returning from a scouting trip through northern Chihuahua, finally arrived. He had nothing to tell but to wait until pending land purchases were completed.

William followed instructions, making camp for himself and others who soon followed and tried to cur his impatience. He made one trip to Deming for supplies and looked the country over in search of farm land. Still restless, he finally hitched up his team and returned to Pleasanton, New Mexico, got the farm work going there and with some seed potatoes returned to his camp in Mexico. There he rented a piece of land from a Mexican and planted his potatoes, but, on account of the drought, not one came up. He then made another trip to Pleasanton, but stayed only a few days, returning to Mexico about May 1. By this time he was disgusted, discouraged and desperate enough to return to Pleasanton, get his family into Utah, face the music, or wait until the storm blew over. Maybe in the country where he had known the greatest peace and prosperity, some of those happy days would return. He left his grove camp below La Ascension May 19 with this intention but decided, sanely, to spend one more Sunday with the Saints in Camp Diaz. There, in the meeting, something happened that changed his whole outlook. A testimony came, a convincing feeling that his mission lay in the land of Mexico., that whatever hardships awaited them, he was part of a people of destiny, and that his place and part in it was to do his best toward fulfilling that mission.

He went to Pleasanton and moved a part of his family not to Utah, but to Mexico. He joined the people at Camp Turley near San Jose and was in camp when the letter was read from Church Authorities appointing George W. Sevey Presiding Elder. William raised his had to sustain him and prepared to move with them to land purchased on the Piedras Verdes River. He was among the number that first settled in Old Town. By the spring of 1886, he had all his family together there. He was by now a financial wreck, his experience in Pleasanton having taken what was left after the United Order failure. But he and his boys dug in, and through sickness, poverty and other ills incident to settling in a foreign land, gradually raised themselves from scratch to a comfortable situation.

He identified himself with the people of Colonia Juarez, did his part toward making it a thriving settlement and set an example of frugality and thrift by getting respectable homes for both his families. He built the first rock house in Old Town, helped survey the East Canal, and made ditches to carry weather from it to town lots. He worked for good roads and took part in all the labors and doings of the people.

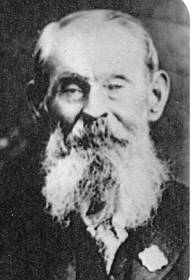

The years of pioneering in Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and finally Mexico, had taken their toll. As years piled up, his step slowed, his eyes grew dimmer. He then took time to write the story of his life for his posterity, the closing paragraph of which reads:

I will leave a large Posterity, and my wish is that none of them will ever do worse than I have done, but as much better as possible. It would be a great satisfaction if I could know they would all grow up to be honest, virtuous, upright, and useful members of Society, as these ideas have been my hobby through life. Possibly I rode them too hard, at times for my own good, but yet I think of the poet that said, “A wit’s a feather, a chief’s a rod, but an honest man is the work of God!”

William endured the privations of the Exodus and moved out of the country with other Church members, leaving two commodious and comfortable brick homes, orchards and town property. But William took it as he did other losses as “all in a day’s work.” He died April 19, 1916, in Colonia Juarez. Almeda and Elsie lived on in Utah for several years, both dying in the homes of their children.

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

Stalwarts South of the Border, page 437