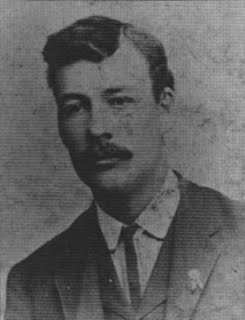

James Elbert “Bert” Whetten

1881-1969

James Elbert Whetten was born July 18, 1881 in Snowflake, Arizona. He was the second son of John Thomas and Belzora Savage Whetten. His father kept a stable where the mail and passenger coach from Holbrook to Fort Apache changed horses.

Bert was five years old when the renegade Indian, Geronimo, was captured and carried to Fort Apache. He and his brother John climbed up where they could look into the big Government wagon and saw him chained to the bottom of it. They really looked him over.

James Elbert was seven years old when his father sold out in Snowflake, preparatory to the move to Mexico. They made the trip in company with John Kartchner and were two months enroute. They settled in Cave Valley where a Ward had already been organized. There Bert was baptized when he was eight years old by his father. Life was hard for the first few years, with little to eat but corn dodger, molasses, and greens, which they were glad to get. His father was a good provider but had to work hard and be on the lookout for every opportunity to improve their situation.

He was 11 years old when the Apache Kid, reputed to be Geronimo’s son, killed the Thompson family at Williams’ Ranch, only two miles from Cave Valley. This put fear into the hearts of all, especially young boys who had to ride the range to keep cattle rounded up. His father had taken a herd of 500 cows to run on shares with a man in Colonia Diaz. Bert had gone along to help move the herd onto what is now the Villa Ranch on the Gavilan. “And that was some job,” he said. But taking care of this growing herd, and keeping them from straying on an open range, was a bigger task. Bert and his brother John kept at this job early and late. They milked cows and took care of the milk. They were not afraid of Mexicans, nor of Americans, many of whom were in the hills prospecting, but Indians were something else.

Bob Lewis, claiming to be a prospector, came into their camp one day and they welcomed him as added protection against the Indians. Little did they know that his friendly approach and his apparent interest in two lonely boys was the greatest menace of all. Their suspicions were not aroused when several of his companions showed up in camp, all claiming to be prospectors, not were they curious about their frequent absence, while Bob remained always close to the boys. He made himself very useful and entertaining around camp, and helped them hunt stray cattle. He even suggested that he would hunt the strays by himself. One evening their cows didn’t come, neither did Bob. A hurried search showed their range had been wiped clean of cattle, except for a few strays that had escaped the rustlers. A thorough search, with help from neighboring cattlemen, revealed that they had all been victims of the famous Black Jack Outlaws, a gang of notorious desperadoes. They followed the trail and found that the cattle had been moved out of the country, by-passing ranches and the unguarded border, into Deming, New Mexico. There they found that Bob Lewis had made shipment of cattle to the East just two days before. They could do nothing about it, although the U.S. Government finally caught and hanged them all. But it didn’t bring back the cattle nor a penny for their sale.

Shortly after the turn of the century, Bert received a call to the Mexican Mission. This was surprising as well as frightening to him. He could handle the wildest broncos and meanest cows, and haul heavy loads with double teams over treacherous mountain roads, but what preparation was that for a mission. His education, too, had been limited. But his church work was less. He not only felt unprepared but unworthy to accept the call. But, schooled to be obedient, he said he would do the best he could.

He was set apart by Elder George Teasdale in June 1905 and entered the Mexican Mission shortly before President Talma Pomeroy was released. With this, he began work that was to be a vital part of his life for more than 50 years. He did his tracting on foot and carried his bedding and books on his back. Whereas before, he had been used to riding and using a pack mule. This was the first hard lesson that turned a cowboy into a preacher. He struggled to learn the Gospel both in Spanish and English. He became Rey L. Pratt’s first companion and made phenomenal growth in the work. He finished his 26 months in the mission field as an accomplished missionary, well informed in the Gospel, and so much in love with the Book of Mormon and the truths contained in it that it never ceased to be his favorite source of study.

On June 29, 1908, he married Lillie O’Donnal and later was sealed in the Salt Lake Temple. With her, a long, happy life was begun. A local mission, to which he was called by President Anthony Ivins shortly after his return, was interrupted by the Exodus. After this event, he was homeless and struggled to maintain his family in a New Mexico logging camp. Then he was called to serve under President Rey L. Pratt, who operated the Mexican Mission in the United States, as the Spanish American Mission. It was a sacrifice, both to himself and his father, to leave their contract at the time. They expected it to be of but six month’s duration. He accepted, and stayed in the field for two years.

Back in Colonia Juarez by 1914, he was called to serve in the Chihuahua Mission when it was organized under the direction of President Joseph C. Bentley. In 1917, in company with President Bentley, he visited the district of El Valle, Temosachic, Namiquipa, Matachic and other places to find Saints who had remained unvisited during the Revolution. This turned out to be the most fateful experience of all. With their wagon loaded with provisions for missionaries in the districts, they had hardly passed El Valle when they were captured by Pancho Villa’s troops, taken to Cruces, Chihuahua, and confined.

Villa was still smug over outsmarting the American soldiers in their attempt to capture him. He was still antagonistic toward Americans and had proved a thorn in the side of the Mexican Government, then in its first struggles to establish a stable government. What he would do with these missionaries was a question. The missionaries partially solved this problem by making friends with the guards and Felipe Angeles, Villa’s military strategist. He was a ready conversationalist, and as soon as he learned of their peaceful mission, confided to them that he was working with the American Government to use his influence with Villa to effect peace with his own government in Mexico. He admitted he was in a precarious situation. Should his identity and mission be discovered by the Carranza forces, he would never get out of the country alive. Then he sympathetically listened to the missionaries while they explained their way of life, the plan of salvation and the principles of the Gospel. The farther they went in their explanations, the more excited he became. Finally he shouted through the door, “Pancho, come here!” When he stood beside him, he exclaimed. “I want you to hear what these men say. They are doing with words what we are trying to do with guns.” Villa nodded and sat down to listen, continuing to nod in between the questions he asked. His final question started them both. “Why have you never told me this before? I have lived around Mormons all my life, and with a Mormon family for awhile in Sonora. But never before have I heard your doctrine explained, or learned the real meaning of your way of life. It might have made a difference in my life.”

At that, Angeles became more excited and solemnly exclaimed, “If I ever get out of this mess alive, I’m going to join the Mormons.” Villa, looking a little anxious, asked,” I might do the same thing. But do you have any place for a man like me?” “Yes,” answered Bert. “There is a chance for anyone doing wrong if he quits and tries to do better. I don’t know anything about you, but I do know that all the Lord wants is a repentant heart.” At which Villa replied, “No doubt you have heard much about me, most of which is untrue. I’ve been bad enough, all right, but not as bad as I’ve been represented to be. Every killing, hold up, or bank robbery has been blamed on Pancho Villa, and of most of them I knew absolutely nothing. But if I ever get to where I can make proper arrangements, I may do just as Angeles has said he’d do.”

Soon after their release, they heard of Felipe Angeles’ capture and subsequent execution. President Bentley and Bert decided if they could get property data, they would have his work done in the temple, for they were both convinced he was converted. Because of the lack of essentials for such work, it was postponed. One day after President Bentley returned from a General Conference in Salt Lake City he announced he had done Angeles’ work in the Salt Lake Temple. The First Presidency had told him to go ahead even if they lacked the essential data. President Bentley died shortly after that and Bert let the matter drop. But as time passed and he was able to spend time in the temple, he became curious to see what had been recorded of the work done for Felipe Angeles. To his surprise he could find no record or anyone who knew of it. Not even after writing Ernest Young, was Bishop of Colonia Juarez when the affair with Villa had taken place, could he obtain confirmation. Together with Antoine R. Ivins and the Temple Recorder, they searched for the record without success. But the unanimous decision of the searchers was that it should be done and Bishop Young commissioned to authorize Bert to do it.

But where would he start? He had a picture of the man which contained his place and date of birth, but where to go to get what else was needed? Then, as if out of the blue, it came. Bert’s son Rey, on business in Chihuahua City was during with a friendly lawyer. In the course of the conversation Felipe Angeles’ name was mentioned. The lawyer at once said he had a book that told much about it and that he could take it if it would help. The book, when procured, contained the record of his trial, Angeles’ speech of introduction wherein he told who he was, when and where he was born, and the names of his parents and much of his early life, all the information necessary to do his temple work. Bert copied all of this onto a genealogical family sheet and sent it to Ernest Young. He took it at once to the First Presidency, who after considering it, sent word to have the work done. Bert was authorized to do it, which he prepared to do at once. But in his search for data on Felipe Angeles, the question of doing the work for Pancho Villa had never entered his mind.

One night he had a dream, so real that when it was over he found himself sitting up in bed. In his dream, Pancho Villa stood at the foot of his bed, dressed in the same suit he had on while they were his prisoners. Villa asked if he knew him. Did he remember the last time he had seen him? When Bert answered “yes” to both questions, he continued. “Do you remember the things I said at that time?” “Yes,” said Bert. “I remember distinctly.” “That’s why I’ve come to see you about now. You taught me something I’ve always remembered. Do you remember what I told you?” “Yes,” said Bert. “You said that if the Mormon doctrine had been explained to you in your early youth, that your life might have been entirely different.” He then said, “I still feel that way, and I’ve come to see if you can help me.” “If there is anything in the world I can do for you, I’ll be glad to do it,” answered Bert. Pancho Villa then told Bert of his trouble, of his inability to go farther without help, and that Bert was the only one that could help him. “Why don’t you go to President Bentley, who is over there and tell him the same story?” “He’s here, all right,” answered Villa, “and I’ve seen him. But he can do nothing for me, and I’ve come to ask will you do it?” Bert repeated his willingness to do anything he could for him. “Can I count on that?” he asked. “Yes,” answered Bert, “you can count on that.” With that he woke up.

Sitting straight up in bed, he awakened his wife who asked in concern, “What’s the matter?” “I’ve been talking to Pancho Villa,” Bert answered. “Oh, you’ve just dreamed it,” she laughed, soothingly. “No, he was standing there at the foot of the bed. Didn’t you see him?” “Of course I didn’t,” she laughed again. “You’ve just eaten too much supper.”

The dream had so shaken Bert he didn’t sleep much the rest of the night. Nor could he get it off his mind the rest of the day. He kept asking himself why he had not been on the search for Pancho Villa’s genealogy while he was hunting so diligently for that of Angeles. Though Villa had not been as vehement in his avowal to join the Church as Angeles, both he and President Bentley felt sure that if conditions were right that he would eventually join. He now decided to do what he should have done earlier. Miraculously, again, he found a friend with a book containing all they needed. In this book he not only found all the information necessary, but also learned that Pancho Villa was christened Doroteo Arango. He copied it onto a sheet, took it to Villa’s widow in Chihuahua City to verify its accuracy, and then explained what he hoped to do with it. To his surprise she not only agreed, but asked what he could do for her. “I’ll send you the missionaries,” he answered, “and you can do for yourself.” This she promised to do.

Bert made a duplicate copy of his sheet and sent it to Earnest Young, who took it to the First Presidency, who in turn said Villa’s work should be done also. Joseph Fielding smith commissioned Bert to do it. In the spring of 1966, with joy in his heart, Bert compiled, thankful to be a Savior on Mount Zion for a man who, bloody through his reputation was, had never harmed a Mormon. Temple officials rejoiced too, when the letter came sanctioning that his work be done. They opened wide the temple doors for those doing it, glad that work was being done for more Lamanites.

This inspiring missionary experience came in Bert’s 85th year. And in what better way could his long service to the Lamanite people end? Bert continued doing his own roping, branding, and caring for cattle until his 85th year. He still makes almost daily trips to his ranch, a few miles distant from Colonia Juarez, where he now resides with his wife Lillie.

Compiled from his journal and tape recording by Erma Cluff Whetten in 1967

Stalwarts South of the Border, Nelle Spilsbury Hatch, page 739