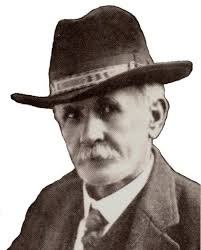

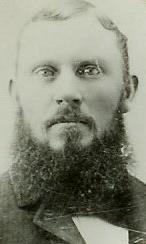

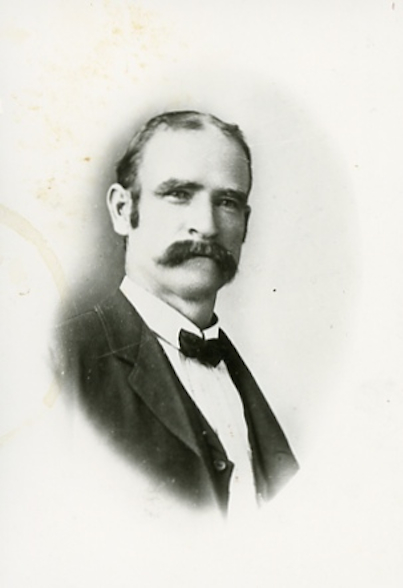

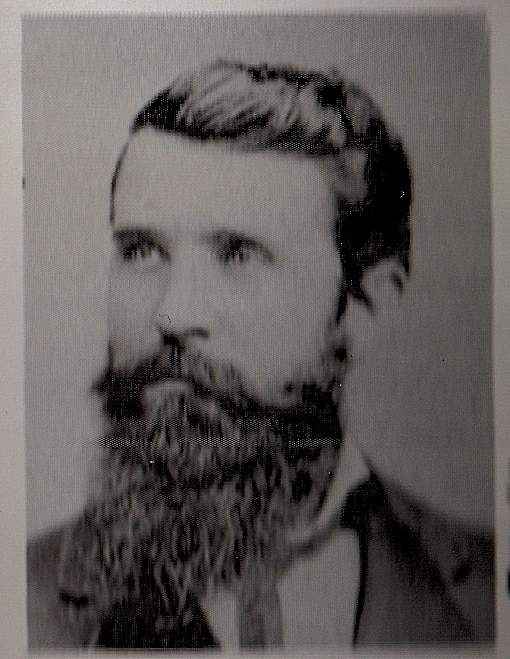

Ammon Meshach Tenney

(1844 – 1925)

Ammon Meshach Tenney was born on the plains of Lee County, Iowa, November 16, 1844, the son of Nathan C. and Olive Strong Tenney.

When Ammon Meshach Tenney was four years of age his parents immigrated to Utah, arriving there in 1848. Two years later his father was called by President Brigham Young to accompany Amasa Lyman and Charles C. Rich to California for the purpose of establishing a Mormon colony at what is now San Bernardino. The family remained there until 1857 when they, with all other Latter-day Saints, were called back to the body of the Church in Utah because of the threat of an invading United States army.

Back in Utah, the Tenney family settled at Fort Harmony, Iron County, in the southern part of the state. Ammon had been named for the great preacher Ammon, told about in the Book of Mormon, had learned Spanish while playing with Mexican children in San Bernardino and was therefore a natural choice to serve as a missionary to the Lamanites. He was ordained an Elder by President Young at the age of 14, and almost immediately was appointed to go with Jacob Hamblin to serve as interpreter on a mission to the Indians.

The expedition consisted of Jacob Hamblin, Ammon M. Tenney and 11 others. The party left for this mission in 1858 and headed for the Colorado River region where they spent considerable time among several trives of Indians living on the east side of the river. Friendly relations were readily established among the Indians through Ammon’s fluency in the Spanish tongue, a language known to the Indians. This was the beginning of a missionary companionship between Ammon Tenney and Jacob Hamblin that extended over a period of 15 years and resulted directly or indirectly in the establishment of numerous settlements in southern Utah and northern Arizona, in opening new roads into unexplored regions, in strengthening weak settlements and in creating more friendly relationships between the Indians and their white neighbors.

Many hardships were encountered. Hunger at times compelled them to eat the flesh of worn-out draft animals and the rawhide carried to mend badly worn shoes. They suffered from excessive summer heat and the biting cold of higher altitudes. There were also many sleepless nights from fear of attacks by red men on the warpath.

In 1869, at the age of 25, Ammon married Annie Sarah Egar and settled in Kanab on the southern Utah border. A family incident a little later illustrates his devotion to Church duty. One of his many mission calls came when a little daughter was critically ill. He lingered at the home after the rest of the missionary group had left. After a day’s delay he mounted his horse and rode off. He had not gone far when he heard an urgent call from his wife, “Come back, Ammon, our child is dying!” Ammon rode back, administered to the apparently lifeless child and she returned to consciousness almost immediately. Fighting back tears, Ammon went again to his horse. “How can you leave us like this?” his wife sobbed. “If I go I have claim on my Maker, but if I stay, I may forfeit that claim,” he replied, trying hard to keep a steady voice. He left and the child lived.

In 1875 Ammon was called to participate in that famous first mission to Mexico in company with Daniel W. Jones, Anthony W. Ivins, Wiley C. Jones, Helaman Pratt, James Z. Stewart and Robert H. Smith. The missionaries, equipped with seven mounts and 17 pack horses, crossed the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry, and then made their way to the Moqui villages in Arizona, passing enroute through Moenkopi, Navajo Springs, and Willow Springs. At the seven Moqui Indian villages the missionaries visited with the Indians several days, then pursued their journey toward the Salt River Valley.

They arrived in Phoenix on November 24, 1875, where they were kindly greeted by Judge C. T. Hayden, who furnished them with letters of introduction to Governor Safford and other influential men of Arizona. In their report to President Young of the opportunities for settlement, attention was called to the many fine facilities on the Salt River Valley for attaining a livelihood. At the village of Sacaton on the Gila River they held their first public meeting with the Indians. The service was well-attended. At Tucson the missionaries were tendered the courthouse of the holding of a Sunday meeting. They were cheered by the kindly reception of the governor. At a military post near Tucson they sold some of their animals and purchased a spring wagon which added comfort to their journey.

It appears that their intention had been to cross the boundary line into the state of Sonora, but they changed their plans when they heard of the unsettled condition of the Yaquis. The party therefore crossed at El Paso, except Tenney and Smith, who were appointed to labor in New Mexico among the Pueblos and Zunis. These two made their way up the Rio Grande River 350 miles to Albuquerque, where they preached for some time without success.

Here Ammon had a dream in which he saw a light in the heavens and became impressed to leave the city of Albuquerque and proceed in the direction of the light. Slowed by jaded animals, the missionaries subsisted mainly on rabbis, the fruit of Ammon’s marksmanship with a rifle. The light followed a distance of 125 miles to Fish Springs, New Mexico, then disappeared. There they met about 20 Zuni men to whom they presented their Gospel message and received permission to hold a meeting, the first since they left El Paso. Thirteen of the leading Zunis were baptized, including their cacique. Ammon reports the great joy he experienced when he led from the waters of baptism the first person he had ever baptized. His strength gave way under the experience. He was helped from the water by his companion and lay prone upon the grass while Elder Smith baptized the other 12 candidates.

Shortly after this the cacique reported an invasion of grasshoppers which threatened destruction of their crops, at the same time calling attention to blessings promised by the missionaries to those who obeyed the Lord’s commandments. Ammon realized that this was a test of the faith of the natives and of the missionaries and trembled at the thought. Gaining confidence he told the cacique that if the Indians would humble themselves on their knees in asking for deliverance from the pest, the grasshoppers would disappear. Ammon’s missionary companion was doubtful and so expressed himself. Ammon’s reply was: “We are the Lord’s servants and He has already manifested His approval of our labors. He will not fail us.” Within one hour, so the Indians reported, following their supplication there was not a grasshopper to be seen. As they arose in their flight they darkened the sun by their numbers. In their enthusiasm the Indians lifted Ammon to their shoulders and danced about, and had they not been restrained, would have worshiped him. One hundred fifty Indians were baptized and three Branches of the Church were organized.

Missionary activities were interrupted by a letter from President Brigham Young instructing Ammon to explore northern Arizona and parts of New Mexico for suitable places in which to plant colonies of Latter-day Saints. Although President Young died soon after, Ammon and his father, Nathan C. Tenney, continued exploration as instructed. They helped in securing a place on the Little Colorado for the settlement of Woodruff. While in New Mexico a letter was received from Church headquarters instructing Ammon to go to St. Johns, Arizona, and make the purchase of a tract of land. There they purchased from Sol Barth, a Jew, and his two brothers land on which one hundred families were called to settle. Ammon was appointed Presiding Elder of the group and the Lamanite Mission in Arizona and New Mexico, until called by David King Udall to be Bishop of the St. Johns Ward.

Trouble arose between the Mexican population and the Mormons, brought on by the Greer brothers, reckless cowboys. During this trouble the father of Ammon M. Tenney, Nathan C., while attempting to be peacemaker, was killed. And during the trying raids on St. Johns by U.S. Marshals against Latter-day Saints suspected of practicing plural marriage, Ammon was harassed almost constantly. The Deseret News of August 1, 1884, reported:

It seems that when Mr. Tenney was first arrested he was given 15 minutes by Commissioner George A. McCarter to say whether or not his first wife should be present at the examination on the 12th of July; and if he did not promise to have her there, he was told that an officer would be sent after her immediately. Mr. Tenney promised to have her present, without the aid of an officer, although she was in a “delicate condition” and the distance to where she was at the time was 20 miles.

About the same time an officer went to Mr. Tenney’s house in St. Johns, in search of his reputed plural wife, and when it was ascertained that there was no such person there, the Commissioner went in person to the house, no doubt thinking to overwhelm Mr. Tenney with his august presence. He told Mr. Tenney that unless he should immediately produce a plural wife for a witness he would issue a search warrant and have the house searched. Mr. Tenney advised him to do so immediately, and this remarkable U.S. officer departed, apparently not in a very good humor.

That night about ten o’clock, Arthur Tenney, a brother of the accused, discovered three men crawling around the house. Mr. Tenney ordered them up onto their feet and when they arose with alacrity, when Arthur discovered that that one of the party was Bill Lewis, the land jumper.

On December 7, 1884, Ammon was tried and convicted of polygamy and sentenced to serve three and one half years in the house of correction at Detroit, Michigan. Two days later he was en route to Detroit to begin his prison sentence. After serving a term of nearly two years, he was given a reprieve by President Grover Cleveland and walked out of the penitentiary on October 12, 1886, a free man. Of this experience while in captivity he had this to say:

We were set at liberty on October 12. I am pleased to say that we are well in body and feeling well in spirits. I can truthfully say the Lord has borne us up through many a dark and dreary hour. We had, however, many things to encourage us, such as visits from friends, the News and Juvenile Instructor, not forgetting the kind treatment of officers who frequently manifested a desire to favor us… Even at the very moment when it seemed as though the heavens were brass over my head and the earth iron under my feet, He [the Lord] strengthened me to press forward… I can truthfully say in behalf of my brethren, as also myself, that in many respects, our minds have been enlightened in a manner they never were before, in regard to the principles of life and salvation, and while I may not know what I may do tomorrow, yet today my greatest desire is to retain in memory what I have passed through. I know it will serve to make me humble, for I know that I have not at all times bee as humble as I ought to have been.

In November 1887, about a year following his release from prison, Ammon was called on a mission to Sonora, Mexico, to labor among the Indians. To accompany him were Peter J. Christopherson, Edward E. Richardson and Gilbert D. Greer. The missionaries set out upon their journey but had not proceeded far when a letter from Church Authorities stated that in consequence of the Yaquis being at war with the government in Mexico there were to continue their labors among the natives in Arizona and New Mexico. From November 1887 to September 1890, Ammon traveled 5,000 miles by team, on horseback and on foot, preached 135 times and baptized 111 souls. His labors were chiefly among the Papago and Pima tribes.

After his release from this mission he went to Mexico to establish a home for himself and family in the Mormon colonies, locating in Colonia Dublan. He was not there long, however, when he was called to reopen the capital city by John Henry Smith and Anthony W. Ivins. His labors there were crowned with considerable success. He organized eight Branches of the Church and appointed local Saints to preside over the Branches. He also set apart 17 local Elders to travel throughout the various cities and villages in proximity to Mexico City.

President Ivins said:

Brother Tenney has been remarkably successful in his missionary labors and had nearly 200 people who appear to be enjoying the Spirit of the Gospel to an unusual degree. I visited all the different towns where we have converts with the exception of one or two isolated places, and held meetings with the people. It was a great surprise and caused my heart to rejoice beyond expression to hear the strong testimonies borne and excellent and logical remarks made by those people. Sectarians, Methodists in particular, are aroused and are doing all they can to hinder the work, but it grows in spite of them. At their conference held in Mexico a few days ago one of the ministers reported that unless something could be done to prevent it, the Mormons would take the entire Protestant population.

At the beginning of 1921, in his 77th year, he was among the Yaqui Indians in the state of Sonora. Elder Tenney said that for 56 years he had been interested in the Yaqui Indians and at last his long-felt desire to be with them was fulfilled. On his first visit to the Yaquis, he found that they had a Quorum of Twelve Apostles which they claimed was organized among them by Jesus. They also said Jesus had instructed them to fill vacancies as they occurred, which they had done. These instructions and many more were given them by Jesus in a personal visit. Ammon asked if they might have received these teachings from the Catholic monks who came with the Spaniards, but the reply was that their religion reached much further back than that of the Spanish conquerors.

Among other exploring expeditions made by Ammon Tenney was one as an interpreter for Major John Wesley Powell down the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. It was said that Ammon Tenney understood all Indian dialects west of the Mississippi River. He was a man of great courage as demonstrated on many occasions during his lifetime. One such was related by Anthony W. Ivins, a lifelong friend:

Nathan C. Tenney had established a ranch at Short Creek, but abandoned it and moved to Toquerville, about 25 miles distant. In December, 1866, three horsemen rode out from Toquerville; to the ranch…Nathan C. Tenney carried an old fashioned cap and ball pistol. Enoch Dodge wsa armed with a light muzzle-loading rifle. The third member of the party, Ammon M. Tenney was a mere boy, with black hair, dark eyes and a slender body. He carried an old style six-shooter and was going with his father to look for horses which had strayed from Toquerville back to the ranch.

At the foot of a bluff a corral had been constructed to which the horses, eight in number, were driven and hurriedly caught and necked together. Signs indicated to the trained eyes of these experienced frontiersmen that Indians were in the neighborhood… The horses were driven from the corral and were heading toward home when the white men found themselves face-to-face with eight Navajos. The Indians occupied the plain, while the white men returned to the protection of the bluffs. What was to be done? That the Indians meant to kill them was plain to the two men.

The boy spoke to the Indians in Spanish and found that he was understood. A parley ensued, and one fo the Indians… leaving his arms, came out into the circle and invited the boy to meet him and arrange terms of capitulation. Ammon was about to comply when restrained by his father. At this juncture the cliffs echoed with war whoops and the men saw eight Indians riding furiously down the plain toward them, their long hair streaming out behind as they unslung their guns and quivers.

“Resistance is now useless,” said the elder Tenney. “What hope have we against 16 well-armed and mounted men?” It was at this juncture that the courage and leadership of the boy asserted itself. Drawing his pistol, he turned down the trail at the base of the bluff, striking the spurs deep into his horse’s sides, and crying, “Follow me,” he rode straight into the Indians who confronted him, firing as he went. The two men followed. Against this intrepid charge, the Indians gave way, and the race for life began. Thus, for more than a mile they rode, the three on the trail, sheltered to the west by the bluff, while the Indians, who were in front of them, behind them, on the plain to the east, kept up a constant fusillade of shots. Several times the boy, who was a superb horseman and better mounted, had opportunity to outstrip his pursuers and escape, as after he returned to encourage his father and Dodge to be brave and come on. He was thus riding in advance when a sharp cry and rider rolling in the dust. The Indians, with bows bent to the arrowheads, were bearing down on his father. Without a moment’s hesitation the boy turned and spurred his horse between his father and the onrushing savages, discharging his pistol in the very faces of the men nearest him. The Indians wavered, scattered, and falling on the opposite sides of their horses, discharged a volley at the boy.

His father declared that he had been shot, and Dodge, also having been wounded by a bullet, implored the boy to escape and go to his mother. Instead of doing this, he assisted his father, to his feet, and turning the horses, loose, with the saddles on, assisted and urged the men to climb to the rocks above. For a few moments the attention of the Indians was attracted to the loose horses and ruing this time the boy succeeded in getting the men up into the rocks, where ne covered their retreat.

A hasty examination showed that the father had not been shot, but that the fall from the horse had dislocated and badly bruised his shoulder. Dodge had been shot in the leg. The boy laid down on his back, took his father’s hand in his, and placing one foot on the neck and the other in the arm pit, with a quick and strong twist brought the dislocated joint back into place. He then placed his hands upon the head of his father, and in a few well- chosen words, laid their condition before the Lord, and prayed that his father might be restored. The man arose and they retreated a short distance to the west where they concealed themselves in some loose rocks.

Darkness came on and with it the Indians left them. When it appeared safe, they came out from their hiding place, and guided by the boy slowly made their way to Duncan’s Retreat, from which place they were taken to their home by friends.

The boy still lives, a courageous, devoted man, but never since and probably never again, will a crisis arise demanding the inspiring exhibition of courage here recounted.

The death of Ammon M. Tenney occurred October 28, 1925 at Safford, Arizona. He left behind a large posterity and a multitude of friends to mourn his going.

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch, Stalwarts South of the Border, page 688.