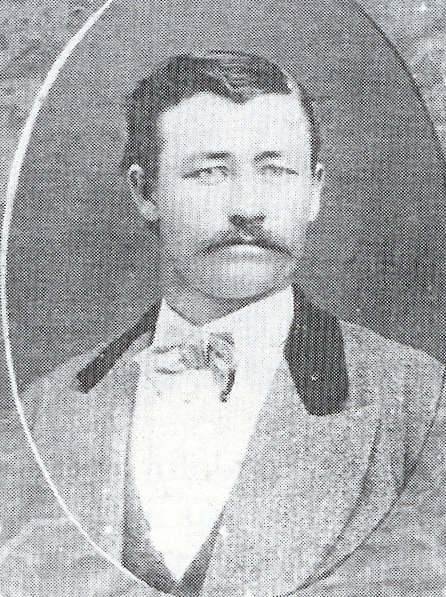

Samuel Edwin McClellan

1867-1957

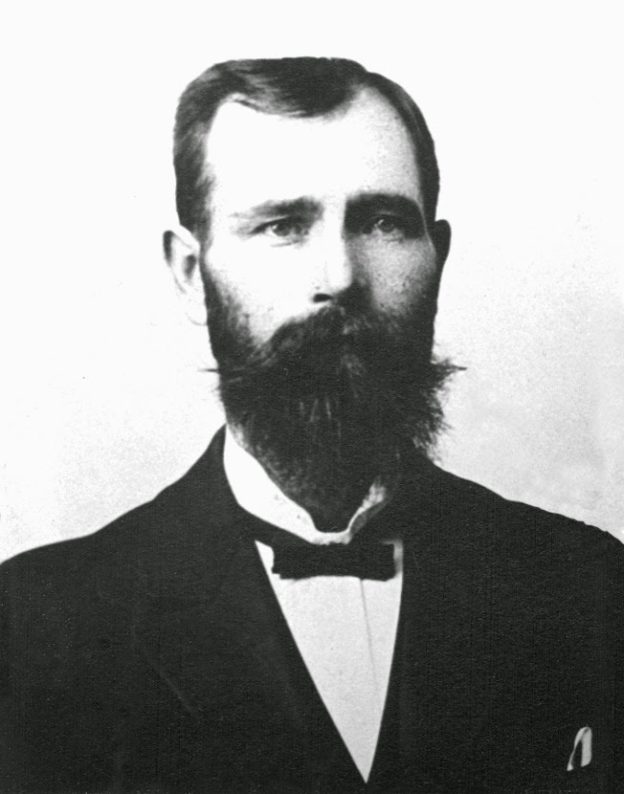

Samuel Edwin McClellan was born July 23, 1867, in Payson, Utah and was ten years old when his father, William C. McClellan, accepted a call to settle Sunset, Arizona.

He was old enough to remember his school days in Payson and his teacher, Annie Ride, who was again his teacher in Colonia Juarez, Mexico, as the wife of Dennison E. Harris. Other memories of life in relatively prosperous and fast growing Payson lingered. He remembered with pride the reputation his father earned as a builder and as town councilman; how hard it was for William C. to sell out, because the Payson people wanted the man to stay more than they wanted to buy his property; that when he did sell, four wagons were required to carry his household goods and merchandise with six yoke of oxen, and a team to hitch to a light wagon to transport the family. Ed remembered riding a horse and driving the loose stock until he got a saddle boil after which he walked and drove them until the boil healed. From September 24 to November 20, 1877, he had the excitement of seeing a new country, then, the anxieties of poor feed for animals most of the time, frequent dry camps because the water holes were far apart, straying animals to look for and delays until they were found, and always rough, jolting roads.

It was still new country when Sunset was reached, where a new life awaited them. Five years in the United Order taught all the participants many things. The McClellans ate at the “Big Table” and were absorbed into the communal family plan that kept food supplied and prepared. Ed, along with other boys, hoed the corn, cane, and turnips, peeled peaches in the cannery, did chores about the sawmill and between times went to school. He learned to be self-reliant, trustworthy, capable, and cooperative, sometimes the hard way. His formal schooling was scattered from Payson to Sunset, to Pleasanton, to Colonia Juarez, a few snatches in the winter months between demands of work about the home or in the fields. This ended in his early teens, but he didn’t stop learning. With an alert mind and a love of reading, he gained wisdom and knowledge to compensate for the lack of formal school work. Later, when his father again became a building contractor in Colonia Juarez and pressed his son into service, Ed found his life’s work. He liked to make things, and the hum of the saw was music to his ears as it ripped through lumber. He was intrigued by the possibilities of the carpenter’s steel square and he took pride in making his work strong and true and expressive of the builder he longed to be. He soon learned, however, that there was more to building than measuring lengths of lumber or squaring timbers and he sought to learn more of the art of planning and blueprinting as the initial step in building. He found his help in a correspondence course to which he zealously subscribed and studied. By the time he had mastered the rudiments of his craft, there were amply opportunities in the furniture factory. It was while working here that he lost a finger to one of the power machines.

His first major engineering and construction job was given him by Anthony W. Ivins, the new Stake President. This was a wagon bridge across the Piedras Verdes River. Before the days of steel and cement girders such a project was a real challenge. Ed drew up plans for the bridge as he imagined it should be and set to work. Stones for the piers were cut and sized at the quarry and hauled in ready to use. While excavating for the solid foundation, unexpected difficulties arose. Underground water filled the holes as fast as the men could throw out the sand and gravel. An extra force of men set to bail the water and a “Chinese Pump” were to no avail. The excavation remained a well of water and flouted continuous attempts to lay the foundation stones. Discouraged and exhausted, the men quit.

In desperation, Ed searched his correspondence course for possible help. There he read how lumber and been used successfully in masonry construction. Although nothing was said of using lumber for underwater construction, he decided to try it. He remembered that embedded planks in a wooden turbine he had recently dug up at the powerhouse were in a perfect state of preservation after years of lying in the damp soil of the riverbed. He devised a heavy plank platform on the water. On this, the layer of stone was added. This procedure continued until the stone-covered platform settled squarely in the bottom of the hole. On this foundation, the pillar could be built up to the desired height. During the 75 years of constant use, these pillars have stood firm against heavy flood water hurled against them each year. They still stand firm as a mute tribute to a young, imaginative builder. When a new bridge to match the new highway was built, these same pillars designed by Samuel Edwin McClellan were used.

Growing prestige as a master builder established Ed as an authority on building problems. This along with genuine integrity made him good teaching material. Superintendent and principal Guy C. Wilson was quick to see this and made a position for Ed in the school system. In 1902, an appropriation was made to create a manual training department for the Juarez Academy designed to give both boys and girls a foundation in manual training. Ed was given charge of the department. His first shop-laboratory was the little brick building on the Bailey lot adjacent to the old Academy building and later, a .umber structure on the grounds of the present site of the Academy.

For ten years before the Exodus of 1912 and form many years afterward, Ed passed his craftsmanship on to young people. In addition to a good foundation in woodwork, mechanical drawing and use of the steel square, Ed dispensed lessons from his life on the frontier which had made him resourceful, honest, and forthright. Students learned that it was professionally sound to be dependable and important to do good, honest, work.

On the heels of this first major assignment, President Ivins gave Ed a second job, acceptance of which was a turning point in his life. The job was to construct a new Academy building. Ed considered it a staggering responsibility. He wrote to teachers of his correspondence courses for blueprint help. They, sensing the dimensions of the job and regarding Ed as a mere student, offered to take it off his hands and do the job for a price. President Ivins, before accepting such an offer, requested Ed to draw up the plans for both the first and second stories for consideration of the Board of Education. Since Ed knew the needs better than anyone else, President Ivins was confident that he would building best what they needed. For long hours, Ed poured over plans which gradually took shape. When a pencil sketch was made to his satisfaction, he presented it to Superintendent Wilson and the Board of Education. The plan was complete with specifications for number and size of classrooms, for stairways, windows, doors and scale drawing of the building.

The plan was accepted and cornerstone laid in January, 1904, and the building completed for school opening time in 1905. Ed kept on teaching his classes but supervised every detail of construction, not only directing the workmen but in off duty hours doing a large share himself. Not a detail was neglected, not a school need was overlooked and the end result was a building with large, ample space and well lighted classrooms, a study hall, a library, a principal’s private office, as well as appropriate entrance halls, laboratories, a stage for dramatic productions, an assembly hall, and a building for multiple services. The assembly hall was especially impressive with a stage at one end. Equipped with scenery and stage properties, it was suitable for presenting plays, operas, and similar performances. With chairs and tables in place, the Church Authorities could preside over conferences, the faculty over assembly programs. Under the stage could be stored the extra benches needed when a dance was to take place.

The building answered the social and educational needs of the community for more than a half-century. It enjoyed a charmed life during the Revolutionary years, left completely unharmed in any way, and still stands a monument to its builder.

The third major building job for Ed was the El Paso, Texas, Mormon chapel. Church architects prepared the plans after Ed and Bishop Arwell L. Pierce had inspected many chapels in the Southwest, studying their plans and costs. But Ed was given a free hand in using his own judgment to improve the building. Construction occurred at a time when materials were subject to many restrictions. Ed gave one-third of his wages as a contribution to the chapel building fund. With the loyal and resourceful support of Bishop Pierce and his Ward in maintaining high standards, notwithstanding great scarcity and panic through the calamity of a bank closing, the building was completed. When completed it drew the admiration and praise of the church building committee and local builders. Ed’s picture was afterwards placedin the finished chapel and he was given credit publicly.

In 1891, at the age of 25, Samuel Edwin McClellan married Bertha Lewis who had come to Mexico to visit her sister, Mrs. Peter McBride. Mrs. McBride, incidentally, was one of the first LDS women to cross the border when the colonies were first settled. Over the 64 years of their married life, Bertha stood by his side as a true helpmate and bore him 12 children. Her third baby was still young when she assumed responsibility for the family so that he husband could go on a mission to the United States. By her own thrifty hands and sale of eggs, butter, and fruit, she maintained her family and her missionary husband.

Ed’s activities in church, civic and social affairs fo the town are still another story. He served as an officer in Priesthood Quorums and Church auxiliaries, as a teacher, as Bishop’s Counselor, and as a member of the High Council. His sound judgment and discernment in times of crisis as well as tranquility were highly valued.

Ed’s early continued practice of reading prepared him to share his storehouse of information and to have unusual insight concerning international events, including American involvement abroad. His own love of freedom made him especially sympathetic to the struggles of people in countries not so free as his own.

Later in life when confined to his bed, Ed expressed his sentiments:

Lying in bed my mind goes round the world, picturing country after country, the people in them and conditions under which they live. It lingers longest in those satellite countries where the poor people can’t call their souls their own and I think how blest I am to be in a comfortable bed in my own home, with all I need within reach of my hand, surrounded by loved ones and friends who are free to come and go as they wish. How thankful I am in that freedom for me and my loved ones has been won by patriots who knew its worth.

Ed sang in the first town choir, played in the first band, was a member of the first dramatic association, and played on the first baseball nine. In choir, Ed’s bass voice was a pleasing support. When amateur operas or dramatic productions were presented, he was usually cast in one of the principal roles. Old-timers would remember best his interpretation of King Ahasuerus in the opera Queen Esther, and his sympathetic portrayal of “Uncle Tom.” In both, he justified the choice of the director.

In the band he played the baritone horn. His was significant part in every band concert, every band-wagon serenade, welcomes to visiting governors, farewells to missionaries, and when the band just played at the band stand in the town park. Music was in his soul as craftsmanship was in his hand. Yet, when a call to a Church mission came, he sold his horn and his tools for money to take him to his field of labor. He trusted to Providence that they would be replaced when he returned.

His deep interest in baseball was in reverse proportion to his smallness in stature. He became an excellent catcher and long after he served well on the town team he retained a lively interest in the game. This love for baseball kept him pouring over results of the World Series as reported in newspapers and radio. He studied the strategy of big league managers and recorded in his memory the names and capabilities of the players occupying the headlines in the news, keeping track of wins and losses of all. Seated in his armchair before the radio while the World Series was in progress with the newspaper on his knee, he kept up to the minute with the game’s progress. “This year was the greatest puzzle of them all,” he said chuckling. “Seven games that looked like any one of them could end the series, where non one scored until the 10th inning, and where the Yanks beat the Dodgers 8-0.” This excitement as he approached his 90th year.

Dancing was a favorite pastime with Ed. During his young manhood, he danced nothing but the quadrille and kindred folk dances. The waltz and other forms of “arm around the waist” dancing were barred by ruling of the Church. Ed still danced the quadrille wholeheartedly and became a foremost “pigeon wing cutter” as well as expert dance caller. He prepared the calls one by one and then added a spice and variety to the dance by his frequent introduction of new formations.

In his last years, years of physical infirmity, he remarked, “I think of everyone who has ever lived in this town, remember my work with many of them, feel sorry for those who were unfortunate and feel glad for those who attained success.”

He died of cancer, July 27, 1957 and was buried in the west cemetery of Colonia Juarez. Twelve children, eight girls, and four boys, survived him. They and the still standing structures of his superior workmanship are monuments to his active and productive life. He fills a unique and respected niche in the history of Colonia Juarez and may rightfully be regarded as one of the colonizers who was responsible for promoting high quality performances in every field of human endeavor.

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

Stalwarts South of the Border, page 432