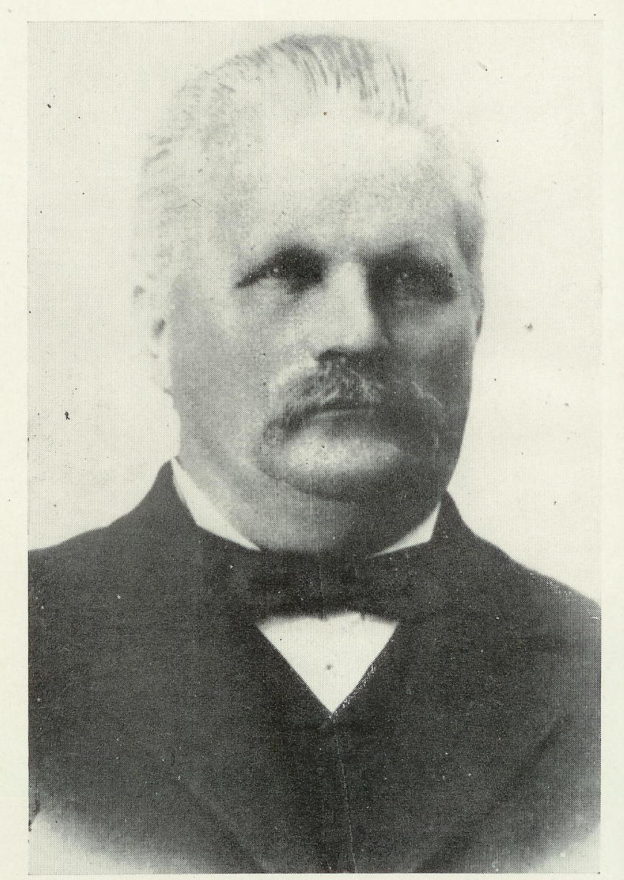

James Berry Chandler

1861-1939

Born January 9, 1861 a Clairborne Parish, Louisiana, James Berry Candler is the second child of James and Elizabeth Frances Stewart Chandler. His father volunteered for the Civil War and left his wife and two small children with his parents, Little Berry and Lucy Swan Chandler. Near the end of the war, Benjamin, a young man of only 24 years of age contracted a devastating disease, died of measles on May 4, 1864 and was buried in Lynchburg, Virginia. He left two children: James, and his elder sister, Elizabeth Matilda Chandler, who was born in July, 1859, Elizabeth Frances, the widow of Benjamin , had to work at whatever she could get to do to earn a living for Jim and is sister Matilda. Jim’s mother would send him to sell butter and hand-made socks that she knitted to earn a living. Jim often had to work all day for a cup of fresh, sweet milk for his supper because if he did not earn it, he had to drink skimmed milk which otherwise would be given to the animals to drink. James Beery Chandler was an independent young man and had a terrible temper. Once when his mother asked him to build the fire in the fireplace and he could not get the fire to burn to suit him, he began to beat the fire with a stick of wood and live coal popped out onto his sister’s dress and burned it to cinders. It was Jim’s responsibility to make the fire for his mother to cook breakfast, and he was expected to get up so early in the mornings that he had to wait a long time for it to become light so they could go to work. Jim vowed that when he was grown and was his own boss he would sleep as long as he wanted.

His mother was remarried in about 1866 to James T. Gaines. She then took her two young children and moved to Texas. She never contracted any of the Chandler’s again. Jim never knew anything about his relatives. There were a few memories that lingered in his mind, but they were so faint he could not be sure what was true and what was not.

James Berry Chandler, or Jim, as he was always called, was raised in Texas on the frontier and had very little chance for schooling. This was one of his larger regrets. He always said his children should never lack for an education. His two great ambitions in life were to make his “little woman” happy and give his children a good education. He felt bitter disappointment when circumstances beyond his control prevented the complete education of his children, but one son and three daughters finally completed a college education.

In Texas they moved several times before finding a permanent home in Rock Springs, Edwards County, where they owned a ranch and small farm. Jim had to go to the fields and help with the farm work and he said his stepfather made fun of him for being so slow and would often stand his hoe up and sit at the end of the row to see if Jim was moving. One day his stepfather told him that if he would hoe the rows clean they would give him an extra portion of his favorite food for dinner. Jim went to the garden and went to work. His stepfather soon came to see how he was doing and, much to his surprise, Jim had hoed up every plant along with the weeds.

His sister Matilda married Henry Thompson in 1878, and part of the time they all lived together at the farm. Jim began to give way to his temper to such an extent that his brother-in-law told him that if he did not control it, it would lead him to the gallows. Jim had never given to serious thought before, but he was sure he didn’t want to end up that way.

Eventually, his stepfather went into the sheep business and Jim herded sheep and took out his earnings in sheep. He worked hard, and by the time he was 28 years old, he had accumulated 900 sheep and several hundred dollars on hand, and decided it was time to go and find a wife. His mother’s older sister, Martha J. Stewart, had married a man named John A. York and was living in Arkansas. Jim decided to go and visit them and look for a bride. On the first day of May in 1889, he and his aunt’s family were on their way to a May Day picnic and passed a group of young people. Jim saw an attractive young lady. Finally, he tugged at his aunt’s arm and said gently, “that girl is mine.” When they arrived at the picnic grounds, he jumped down off the wagon and kept looking for her. The girl was Beaulah Hazeltine Brown. She was indignant when she heard about the stranger that wanted to meet her, so she refused. Later at another gathering they met again and became acquainted. Him left soon after that and went back to Texas where he spent all that winter fixing his farm for his intended wife, because he planned to marry Beaulah in the spring.

Beaulah’s father depended on his daughter for everything. He strongly objected to her marriage, giving as one reason their difference in age to meet at a cousin’s home in Malvern, Hot Springs County, Arkansas. On the 30th of May, 1890 they were married. When her father and brothers returned home from work for dinner and found she was gone, the father set the two brothers after her with guns, giving them strict orders to bring her back home even if they had to us the guns. But the boys missed them. Jim and Beaulah went to the train station and left Arkansas and went to Jim’s home in Texas.

Their first child was born June 16, 1891, a daughter, and they named her Missouri Frances Chandler. A son was born the following year on August 12, 1892, and they named him William Lion Chandler. On November 2, 1893 they had a daughter named Hattie Matilda who died three months later on February 10, 1894. James Walter Chandler was born September 23, 1895, and Tommie Brown Chandler was born May 24, 1897. The name Tommie was the maiden name of Beaulah’s mother (Missouri Williams Tommie) and his middle name was her own maiden name. Albert Jasper Chandler was born February 4, 1899. All seven of these children were born in Rocksprings, Edwards County, Texas.

In about the year 1898, Jim sold his ranch and bought the city water works and blacksmith shop in Rocksprings, Texas. He did all the blacksmith work and furnished water for the entire town. He gave water to many people who were too poor to pay him and he was well liked by everyone that knew him. Jim was appointed Road Overseer for one term in Edwards County. His duty was to summon the men of his district to work the road when work needed to be done. At that time, there lived a man in the district who was called a bully and had been in the habit of dodging his share of road work. One time this man failed to appear so Jim reported the case to the proper authorities. After court adjourned, this bully jumped onto Jim. They had quite a struggle before Jim laid him out cold.

Beaulah was not in good health, and the doctor seemed to think another climate might be better for her. Jim sold everything except 15 head of horses, and, on the third day of April, 1900, the family left Texas for Arizona. He talked to his sister Matilida and her husband Henry Thompson and family into going with them. Before leaving, all their neighbors came by to bid them goodbye, and someone asked Jim why he was going to Arizona. He answered jokingly, that he was moving out among the Mormons to get another wife. Naturally they had a big laugh since all any of them knew about Mormons was polygamy.

James Berry Chandler and Beaulah took five young children on this trip, ranging in age from one to nine. Matilda and her husband had seven young children. Each family outfitted a covered wagon holding all of their earthly belongings. There was a white-top buggy for the two women and the children who were too small to walk. Beaulah drove the white-top. Henry drove one wagon and Him the other. Henry’s two older sons Will and John Thompson, drove the loose horses. They started out with 15 head but, since it was still spring, several colts were born on the trip.

Instead of going to Arizona, Jim settled in Lincoln County, New Mexico. The journey had been more expensive than they had expected and the teams were tired. The youngest baby, Albert, and Matilda’s daughter Lottie, both about two months old, were very sick. Everyone expected the babies to die. They had a bad case of summer complaint or dysentery. They stopped in a place called Silver Springs Canyon, which was across the mountains from Alamogordo, New Mexico. It was near a goat ranch. Someone told them to feed the babies goat milk and they would get well. The rancher was good to them and he let them have all the goat milk they needed for the babies.

The two families landed in Capitan, New Mexico in July. They camped near a creek. The men obtained work in a coal mine in Colora, a few miles from Capitan. In Colora the houses were all alike. You had to count them to be sure you were in the right one. In a few weeks they left and went to Angus, New Mexico, in a small valley where Jim took work on a farm.

When it was crop planting time, they rented a small farm near a stream and raised vegetables and chickens to sell. They also had a little orchard and raised apples. They used to earn money by catching gophers and selling them for the bounty which was about 10 or 12 cents apiece.

It was about four to six miles from their place to the post office in Angus, New Mexico. On Saturday afternoon, the family was going into town to get the mail and do the weekly shopping, when they met Henry coming home from town. He said, “Jim there are two preachers over there who preach the best doctrine I have ever heard. They will preach tomorrow, come over and hear them.” When he told them the preachers were Mormons, Beaulah said, “I’ll not go to hear them.” Beaulah was raised a “hard-shell” Southern Baptist. She stayed home that Sunday and Jim went to hear them preach. After the service, Jim went over to the Elders and asked to see their horns. Of course they laughed and took off their hats to show their horns. Jim told them he was very much impressed with the service. The names of two missionaries were Elder James T. Lisonbee and Elder Edward R. Jones.

One day Jim went to the little town of Capitan with vegetables, eggs and chickens to sell. After selling his load and buying groceries with the proceeds, just as he was leaving town, he happened to see the two Elders. He knew they were on their way to his house and he thought about what people would say if they saw him with the missionaries, so he decided to turn around and take another way out of town. James Berry Chandler went home, fed and watered his team, came into the house and no more than sat down by the fire than a knock came at the door. It was the two Elders. They had walked all the way from town, between four and six miles. Jim felt ashamed of himself that he invited them in and confessed what he had done. Of course the Elders just made a joke of it.

After supper, just before time to retire, it was always the family custom to have a visiting minister (of any church) read a chapter in the Bible and say a prayer. Elder Lisonbee read, then asked the young Elder Jones to offer prayer. He appeared quite bashful and spoke slowly. The family never forgot that prayer, there was something very impressive about its simplicity. He asked the Lord to bless the night’s rest, that all might have strength to arise in the morning able to go about their work, that dreams might be for the enlightening of their minds, and that all might understand the truth.

That night Beaulah had a dream. To quote her own words: “I dreamed that I went to Salt Lake City and went to a beautiful temple which was enclosed by a rock wall. I went into the temple, and had to go through a tunnel to get to the temple proper, then I was taken to the baptism room, where there was a fountain of water resting on 12 oxen. The head and shoulders were turned away from the pool. Then I strolled through the temple grounds, I saw many statues and all kinds of flowers.” Although the dream was clear and very impressive she did not mention it to anyone the next day. They had a good visit with the two Elders and soon they left, promising to return in two weeks.

During those two weeks, Beaulah had another dream. Again, to use her own words; “That time I was sitting on the porch, when a man walked up and introduced himself to me. I had never heard his name before; he said he was Brigham Young. He sat next to me and we talked for a while. At the time I did not realize the significance of this dream.“

In two weeks, the missionaries came again; it was about the same time of day as it had been before. After the evening meal was over, and the work was done, Beaulah went into the living room with the others who had gathered around the fireplace and were talking about many things. They Elders were explaining various principles of the Gospel. Just as she walked in, one of the Elders had just taken out a Church paper from his valise. On the front page was a picture of the prophet Brigham Young. Beaulah was quite surprised and she said, “That’s Brigham Young isn’t it!” The Elders asked if she had ever seen that picture before and she said, “No, but I saw the man in a dream the other night.” She then related the dream about the temple, and the Elders said she could have described it better if she had been there in person.

One thing Beaulah noticed and liked about the Elders was that, when they came to the house, instead of expecting to be treated as a special guest (as the ministers of the other churches of that day did) they would offer their services to help with the work around the place. One Elder used to milk the cows, and the other helped with the dishes. The Chandler house became their headquarters during the two or so years while the family was in New Mexico.

James Berry Chandler bought a little book called, The Voice of Warning, by Parley P. Pratt. He also bought a Book of Mormon. At first Beaulah did not want to read anything. But her husband was not a good reader, so he would ask her to read to him, which she did. In reading The Voice of Warning, Beulah became interested in the promise made by Moroni in the Book of Mormon. When Beaulah read that she decided to test it. So she began reading the Book of Mormon. She was impressed and knew in her heart that if the Bible was the work of God, so was the Book of Mormon.

On Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1901, they were baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. A Brother Lamb, a former Baptist Elder, and his family were baptized the same day.

A year after they joined the Church, they had another child. She was born November 22, 1902. They named her Ruth Florence Chandler. A few months later, the family was stricken with influenza. The three youngest children contracted pneumonia. Andrew Berry Chandler, age two, died on January 18, 1903 and Ruth Florence Chandler, age two months, died on January 26, 1903. The Elders had just just left the Chandler home days before the first death occurred. There were no other Saints in the community. After the first baby died, the other two were too ill for the parents to leave them, so a friend had to arrange for the grave and bury the baby. Jim felt there must be some kind of funeral service. There was no one there but himself, so he and the two older children sang “Redeemer of Israel.” He felt that the song would take place of a funeral service.

On Christmas day, December 25, 1903, Jim and Beaulah had another son, and named him Franklin Richard Chandler.

Their ninth child, Jesse Stephen Chandler, was born April 11, 1906 in Capitan, New Mexico. Jim acted as the doctor and nurse for his wife at this birth. This was the year Jim felt an urgent need to take his children where there were Saints and a good school. So again Jim pulled up stakes and went to Mexico.

They moved to Colonia Dublan, where there was an organized Ward. It was a dramatic change in life style for them. The LDS way of living was very new to them and they had a difficult time for a year or so. They had always lived on the frontier. Jim had a difficult time getting established. But the family was blessed in many ways.

One of their neighbor’s crop of potatoes was flooded by heavy rains and ruined. He let the crop go unharvested and the next year it grew up in the weeds and tall sunflowers. He told Jim if he would clear the weeds off all the ground and plant it again, Jim could have the potatoes for his work. Him went to work and harvested enough potatoes to last the family through the winter. They picked fruit for the neighbors and canned enough for themselves. They lived on bottled peaches without sugar and bread and potatoes without seasoning except salt. Despite the re-adjustments, the family loved living among the people and were determined to never live where the Church organization did not exist.

The first winter in Dublan, their baby boy, Jesse, took the measles and spinal meningitis, and he nearly died. About the seventh he appeared to be breathing his last. They called the Bishop and Ammon Tenney who administered to him. All at once he relaxed and went to sleep. The next morning he was well and sat up all day.

Two daughters were born to the family while living in Colonia Dublan. Beaulah Alva was born March 24, 1908 and Hastletine was born February 28, 1910. Jim finally obtained a contract with the railroad, and the family started to save money for a trip to Salt Lake City. By June 1911, they had enough money saved to go to the temple to have our family sealed.

In the meantime, the people were told that they might have to leave Mexico and not to make any obligations where they had to go into debt.

The boys were working with their father on the railroad, saving some of their earnings for spending money on the trip to Salt Lake City. When it came time to go, their son, Tommie, was sent to Dublan from the railroad camp to tell his mother when to leave. He came on horseback and, on his way, asked his father to let him have the money he had saved which was $25.00. His father told him he had batter leave the money he had saved with him for fear he might lose it on the way home. Tommie begged his father to let him take it, so he finally gave it to him but warned him to be careful. On the way he was robbed by two Mexican soldiers who took the saddle and bridle off the horse, search him, and took the money and left him to ride about 20 miles bareback.

The family had nine children, and the trip to Salt Lake City on the train cost them between 11 and 12 Mexican dollars. They were gone a total of two weeks.

While they were in Salt Lake City, word came that the trouble in Mexico was about settled, so they went back and Jim signed a new railroad contract. He went into debt for new material and bought new dump carts.

In 1912, soldiers demanded all their guns and ammunition from the colonists, and took cattle and horses at will. The colonists were told to leave for their own safety. The younger children and Beaulah left with the women and children in the first Exodus. Jim and the two older boys remained working on the railroad contract and, sometime after the rest of the family left, rebels came and robbed the road camp, taking everything. They captured Jim and took him to help fight a battle at Cumbre Tunnel. Part of the trip was after dark, so he managed to escape.

The rebels loaded all the supplies on wagons and left. That night the work animals made their way back to camp. The two boys tailed them to where they left the wagons and proceeded to the pack animals. The boys recovered the wagons and teams and returned to Dublan. They then received news that the women and children were in El Paso where the city provided camping places for them. From there, the U.S. Government and Church Authorities provided transportation for the people to whatever location they desired.

The James Berry Chandler family chose to go to Graham County, Arizona. In September 1912, Jim and the two boys went to Arizona. They moved around several times for the next three years, from Hubbard to Pima, and finally to Thatcher. They chose Thatcher so that the children would be close to a school.

Beaulah’s brother, James Brown, died in July, 1917, and left her $2,500 in cash as well as land in Corpus Christi, Texas. When they inherited the land, they soon discovered that they owed back taxes. A few years later that property proved to have 40 acres of oil on it, and the people that took the property became millionaires.

Jim and Beulah were grateful just for the cash inheritance, and bought property in Red Rock, Arizona. Beaulah was called to be the Relief Society President in the Franklin Branch. Eventually the family returned to Thatcher to make that their permanent home. Jim Chandler died June 27, 1939.

Submitted by Eileen Miller, granddaughter

Stalwarts South of the Border,

Nelle Spilsbury Hatch, page 104