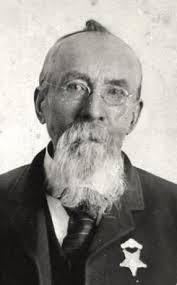

William Morley Black

(1826 – 1915)

The son of John and Mary Kline Black, William Morley Black was born February 11, 1826 in Vermillion, Richard County, Ohio. William’s own account follows:

When I was eleven years old, one of our neighbors, a man whom we had always respected by the name of John Potts, got into trouble, and my father made his bond in the sum of $500.00. When trial came on, Potts could not be found and it took our farm to pay the bond. At that time Illinois, a new state, was widely advertised as a place homes were cheaply obtained, so Father and three of our neighbors moved into Lawrence County, southern Illinois, and purchased homes near where Bridgeport now stands. It was a wide, level, beautiful country with groves of timber and stretches of prairie, with cold springs and streams of cold clear water abounding in fish. The drawbacks were occasional swamps, giving rise to malarial fevers and here — after two years of hard labor in building a new home – our first great sorrow came to us in the death of our father.

My brother Martin, being the first born – the responsibility of managing in the home rested upon him, while I aided what I could by hiring out and giving the family my means. For two summers I worked in the brickyard getting 37 and one half cents (a) day. Winters I hired to do farm work, getting $5.00 a month. When 17 years of age the family consented to let me strike out for myself and I went northward and stopped in the vicinity of where Peoria now stands. The first summer after leaving home I worked on a farm, getting $8.00 a month, which was considered good wages at the time. The second summer I made an agreement with a Mr. Brockman, a contractor and builder, to work two summers with him. He was to pay me $6.00 a month and learn me the trade of masonry. I worked one summer when Mr. Brockman died, which ended that adventure.

In 1845 a little town called Cuba was started. I secured a town lot and began to gather material to build me a home. At that time I had made the acquaintance of a family by the name of Banks. I was temperate, industrious and saving, and during the summer erected, mainly by my own labors, a tidy two-roomed house; and in February 1845, I married Margaret Ruth Banks. I took quite an interest in politics, and in 1848 I ran for sheriff on the Democratic ticket and was elected. In the winter of ’48-’49 the news of the discovery of gold in California created quite a fever in our town and I caught it. In the spring of 1849 a joint stock company was formed to go to the gold field. I resigned the sheriff’s office and paid one hundred dollars into the company which entitled me to a passage by team across the plains of California…

William Newell was elected captain. I was selected as a teamster. On the third day of April with light hearts and high ambitions we kissed our wives, children and parents goodbye and took the trail for the Eldorado of the West. One hundred miles from Cuba brought us to Nauvoo, Illinois, on Saturday, and we rested the Sabbath. I strolled through the streets of the city. Many of the homes were vacant. Those that were inhabited were occupied by people whose language was strange to me. I was told that the builders of the city were a lawless sect who for their crime had been driven out; and their beautiful substantial homes and become a prey, almost without price, to a community of French Icarians who purchased from the mob at low prices the homes of the exited Mormons. Here we crossed the Mississippi River and followed westward the roads made three years previous by the fleeing fugitives from Nauvoo. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Icarians#Nauvoo.2C_Illinois

On the 24th of July we entered Salt Lake Valley emerging from Emigration Canyon. We were all on tip-toe, anxiously waiting to see what kind of civilization the Mormons would exhibit to us. Descending from the bench lands, we soon encountered well-cultivated fields that extended westward, evidently small compact holdings, to the very doors of their homes. Every field was bordered by a newly-made irrigation canal. And the scarcity of weeds gave evidence of careful culture. Passing through city, I saw the marking of several blacksmith shops but not a saloon, barber pole, tavern or even a hotel could I see. But in the northern and thickest settled part of the city we passed a large brush bowery constructed evidently as a screen from the sun and used for public gatherings, and today it looked as if the entire community, both young and old, male and female, were assembled there. At first I thought we had lost of reckoning and that this was the Sabbath day – but this could not be as the Mormons were an unchristian lawless sect and doubtless paid no heed to the Sabbath. Passing the city we camped on open ground on the bank of a small stream called the Jordan. Across the street opposite us stood a low two-roomed dirt-roofed adobe house. The laughter of children announced to us that the inmates of the home had come. I met the father whom they familiarly called “Uncle Buck Smith.” I asked if myself and companion could get supper with them. He hesitated and finally said, “I am fearful our simple supper would not please you gentlemen. We can give you a supper of meat, milk, and pigweed greens, but bread we have not. You see, the flour we brought a year agoa has given out. We have not had bread for three weeks and have not hopes of any until our harvest comes off.” I gave them a pan of flour and in return partook of a very relishable meal. The dirt floor was cleanly swept. In fact, everything, though crude and primitive, was neat and tidy. When seated at the table Uncle Buck said, “Be quiet, children,” then he gave thanks for the amply supply of food and asked the Father to bless it to our use. This was the first time in my life that I had heard a blessing asked on our daily food and this prayer fell from the lips of an uncultured Mormon.

Toward evening I met another Mormon, a Mr. William Wordsworth. He was a man of pleasing dress, evidently well educated. He explained to me the nature of the gathering in the bowery. Two years ago today the pioneer company of the Mormon people, the fugitives from Nauvoo, entered this uninhabited and almost unknown valley, and their thankfulness was enhanced by the hope that they were beyond the reach and power of their old enemies who had cruelly mobbed and persecuted them for the last 15 years. Their suffering and martyrdom of their Prophet was all news to me and I wished to know the nature of their worship — which, as they affirm, was the primal cause of all their suffering. To my surprise Mr. Wordsworth invited us to attend their church services the next day. I accepted the invitation and he promised to call for me.

Sunday, July 25, 1849 is the day ever to be remembered by me. Mr. Wordsworth called early and after chatting 10 or 15 minutes with members of the company and again extending an invitation to us all to attend their church, he and I walked together to the bowery. We secured seats near the front of the congregation. On the west was a raised platform of lumber on which were seated some 20 of their leading Elders, on neatly-made slab benches were the choir and congregation. Services opened with singing and prayer, and the sacrament (bread and water)of the Lord’s Supper was blessed and passed to all the people. Then a man of noble, princely bearing addressed the meeting. As he arose Mr. Wordsworth said, “That is Apostle John Taylor, one of the two men who were with our Prophet and Patriarch when they were martyred in Carthage jail.” The word “Apostle” thrilled me, and the sermon, powerful, and testimony that followed filled my soul with a joy and satisfaction that I never felt before and I said to Mr. W., “If that is Mormonism then I am a Mormon. How can I become a member of your church?”

“By baptism,” he answered.

“I am ready for that ordinance.”

He replied, “Do not be in a hurry. Stay here and get acquainted with our people. Study more fully the principles of the gospel. Then if you wish to cast your lot with us it will be a pleasure to me to baptize you.” That night I slept but little, I was too happy to sleep. A revelation had come to me and its light filled my soul. My desire and ambition for gold was swept away. I had found the Pearl of Great Price, and I resolved to purchase it, let it cost what it would.

After a few days rest the company pushed on for California, but another man drove my team. I gave them my all, and in exchange received Baptism at the hands of Levi Jackman. I had lost the world and become a “Mormon.” “He that putteth his hand to the plow and turneth back, is not worthy of me.” As they continued their journey, it was a little painful; their warm cheery good-byes touched me in a tender place; as neighbors and companions for 1400 miles on the plains, they had become dear to me and the parting turned my thoughts back to home and loved ones. A shade of homesickness rested upon me. I stood alone with strangers, but “Uncle Buck Smith” sensed the situation and strengthened my young faith with brotherly sympathy inviting me to take my home with them, and he contrived to set me to work which is a sure antidote for the blues.

One day President Wells told me that I had been selected, as one of a party, to go to Sanpete Valley and aid in making a settlement. I did not wish to go as I had been told that it was a cold frosty place, too high in altitude for agricultural purposes and I felt that my condition would not be bettered again. I could not see just what right the President had to call me. I understood and expected them to guide me in spiritual matters but this was of a temporal nature and beyond their jurisdiction. These were my thoughts and this Pioneer Call was the first trial to my faith. I am pleased to say the pause was only for a moment. On reflection, God’s dealings with Noah, Abraham, Moses, Lehi and Nephi was strong evidence that reasoning and tradition were incorrect. Was not God the Author of the world, as well as the Gospel? If he builded the earth, why not govern it? If it requires union of spirit and matter to bring the exaltation of man then it must be that the Priesthood has a right to direct in material and temporal things, as well as in Spiritual things. The next time I met Brother Wells I told him I was willing to go to Sanpete or anywhere else.

I want my descendants, who may read this sketch, to bear in mind that I was a new disciple and in my mind was still wrapped in the ideas and thoughts of sectarianism, and obedience to the requirements of the Priesthood was a new doctrine to me. But the call set me to thinking, and studying, and led to an increase in knowledge.

Today I cannot recall the exact date of my starting to Sanpete, but sometime in February 1850 in company of Ephraim Hanks, William Porter and four others the start was made. There were no settlements south of Salt Lake City until we reached Provo, where the settlers were living in a fort. Our progress was slow on account of muddy roads from the melting snows and frequent storms that came at that season of the year. At the crossing of the Spanish Fork Creek, as we were moving in a narrow road cut through heavy willows, a troop of Indians appeared on the opposite bluff and opened fire on us. I was driving the lead team and I am free to confess that I halted as soon as I could. Eph Hanks, the leading spirit of the company, stepped fearlessly to the front and in Spanish held a parley with the Red men, who under the leadership of Josephine, a reputed half-brother of Walker (Chief Wakara) The Indians refused to let us advance unless we would pay tribute. We gave them one sack of flour and three sacks of corn meal as a peace offering, which was in harmony with President Young’s axiom that it is cheaper to feed them than it is to fight them. It was by President Young’s wisdom and foresight that Hanks was along. He is by nature an athlete of wonderful power. He loved excitement and danger, qualities that gave him influence with the Indians. On this occasion they had the advantage of us — and had they continued — we could not have escaped. The whistling of bullets was new music to me, and I was glad when the music ceased and we received no further harm than by scare and the loss of four sacks of provisions.

The trip was a hard one. Mud and bottomless roads in the valleys. And over the divide at the head of Salt Creek the snow was from two to four feet deep; for several miles we could move but two wagons at a time. I have often thought how wise it is that we cannot see the end from the beginning for often the difficulties would be greater than our faith, and we would fail to make the progress that we do. After two weeks hard struggling, we reached Manti on Sunday and received the heartiest of welcomes — old and young turned out to greet us. In a short time all of our little company was made to feel at home with old accountancies. I alone a stranger without kin or acquaintance so when Father Morley, who presided at Manti came and asked if I had friends to stop with, I told him I was an entire stranger. “Well, then come and live with me and be my boy.”

I went for two years and my home was with Father Morley. I learned to love him as my own father. No bargains ever made. I never asked for wages and never received any. I worked at whatever was most needed; as harvest approach we saw the need for grist mill, as there was none within 100 miles of us. Phineas W. Cook and I undertook to build one. We went to the canyon, cut and hewed timber, then hauled it to the mill site at the mouth of the canyon one mile above the Fort. With broad axes and whip saw me prepared and directed to frame the mill. In the meantime Charles Shumway and John D. Chance have built a sawmill just below us. From there we got lumber to finish our mill and President Young came to our assistance by furnishing a pair of Utah homemade burrs. My Christmas our little mill is running improved a great blessing to the infant settlement of Sanpete.

All this time I made my home at Father Morley’s and had learned that Adam and Eve were married before Adam’s fall. Hence, marriage for Eternity, as well as for time, and the union till death do you part, is of human origin. Then he pointed to Abraham and Jacob who founded the house of Israel; then he cited the revelation given to the Prophet Joseph Smith, which says, “I reveal unto you a new and everlasting covenant, and if you abide not the covenant then ye are damned, for all who will have of blessing at my hands will abide law that was appointed for that blessing.” To my understanding at that time, that meant “plural marriage.” I accepted it. I met a young lady of good family who please me and I pleased her. I told her of my wife and two children and of my desire to go and bring them to Utah. With this information and understanding she was willing to marry me, and in February 1851 I married Mary Ann Washburn. Patriarch Isaac Morley performed the ceremony.

I started back to the states for my family and on 20th of December reached South Canton. To my joy I found my wife Margaret and the children, Martin and Martha there, well. She received me as one from the dead though I had written to her. Yet her friends had prophesied that I would never return. I will be brief and relating the outcome of my return. I was full of love and zeal for Mormonism and my wife’s family, especially her parents, were full of bitterness toward Mormonism. One evening in answer to a question of mother Banks, I told them I had been baptized in the Mormon Church. My mother-in-law was wild with rage and abused me without stint. I was prepared for the outburst and calmly and kindly made explanations and tried to turn away her wrath with mild answers. Father Banks refused to talk further than to give me to understand that, as a Mormon, I was not welcome beneath his roof. Then they retired without bidding us good night. There was no sleep for myself or Margaret that night.

It was one of the sorrows of my life. It was not a trial, my faith is not shaken. I received life and I knew my duty and was as well-to-do it. As daylight approached I said, “You are my wife and I love you, but I love God better. I’m going to harness my horses and leave your father’s roof. If you want to go with me happier things ready. Otherwise, I shall take Martin, leaving Martha and did you goodbye.” At daylight I drove up to the door. Her bedding was tied and everything packed and ready. I lifted her and the children into the wagon, wrap them in quilts for it was storming furiously. By her suggestions I drove to William Biers, who had married one of her schoolmates. They lived two miles away. They were surprised and amazed that received us kindly. We stayed that day, thankful for the hospitality for it was one of the worst blizzards that I ever have seen. I shall never forget the day and the incident. That time on Margaret’s trust in me was a great comfort. I resolved the heed President Young’s parting counsel, “Be a good boy and come back as soon as you can.” By the time we returned to Utah, Margaret had been baptized and was prepared to meet the new conditions and accepted cheerfully her share of the increase responsibilities that plural marriage brings to all. Margaret and Amy lived together cheerfully and our lives were happy and contented.

In 1874 President Young and George A. Smith visited southern Utah put forth their best efforts to organize us into working companies called United Order. Those who join the order, consecrating all that well, seemed baptized with the new zeal that fill their souls with energy, goodwill and brotherly love, while those who oppose that were filled with jealousy and hatred. In the Order people sold their homes in choosing flat uncultivated land two and a half miles north of Carmel, laid out a town and named it Orderville. Under Brigham Young’s watchful eye and counsel they were greatly prospered. I cast my lot with the Orderville community consecrating my farm, teams, and interest in the Kanab mill. In fact, my earthly all was put upon the altar and sacrificed in a cause that I believe was instituted for the good of the human family. I was placed in charge of the boardinghouse with seven assistants. We prepared the food for all community, numbering it first 200 but increasing to 600. We got to the system and method so that our meals were served as regular as clockwork. On economic lines the hotel is a grand success. No waste of substance and eight persons served breakfast to a hundred families for one year. The work was confining, yet I was contented.

In 1871 I married Louise Washburn, daughter of Abraham and Clarinda Washburn. My families live together in Orderville. We had good schools and well attended meetings. Indeed life there was a spiritual feast. Our wisest men had been called to the front as directors and above them was in the church was Brigham Young. That stood as a beacon of light to us — and when the lights went out, we were a ship that had lost its pilot. The sailors remained, but they were soon divided in counsel and with division can weakness. When the Orderville United Order dissolved, I moved to Huntington, Castle Valley, bought me a farm of 80 acres which my sons cared for while I worked in Seeley Brothers Grist Mill for three years.

Then I spent one year playing “hide and seek” with the U. S. deputy marshals; but I got tired of the play so I took Louise, the youngest family and skipped for Old Mexico. I went with two teams, leaving Huntington November 13, 1888, passing through Rabbit Valley and up the Sevier by Johnson’s, then across the Buckskin Mount into Lee’s Ferry. The nights were cold, but no storms. We passed up the Little Colorado in Arizona in the day before Christmas to reach St. Johns, where my own son William G. lived. We spent a pleasant week with them and then moved on. The 4th of June 1889 I reached Colonia Diaz, Old Mexico. So here I am in a foreign land, not a choice but of necessity, in mt own land made a criminal; yet I have not injured any living person. The law that makes me a sinner was enacted on purpose to convict me and was retro-active in its operations. To me it is legally unjust, which adds a sting to the cruelty; but what can’t be cured must be endured so I take as little of the medicine as possible and try to be cheerful.

November I received a letter from W.R.R. Stowell of Colonia Juarez, pushing me to come and help put the machinery into his grist mill. I went at once and then cared for the mill for three years. I then found employment at Jackson’s old mill near Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. I had charge of it for two years and for a year I was superintendent of his new roller mill. When Jackson sold to Memmott and Co., I continued as superintendent. In 1897, feeling the need for a rest, I left the milling business and had a one year of Jubilee like the patriarchs of old. I spent the 24th of July — Pioneer Day — in Salt Lake City, then visited my sister Rachel in Beaver. From Beaver I returned to Mexico in found employment in Stowell’s grist mill. For nearly 2 years I attended the mill, sometimes night and day, but the best of my days were passed. The evening of life was approaching. My lungs commenced leading in one day I broke completely down. Father Stowell came to see me and pronounced my condition serious. He hurriedly brought Dr. Keats. They administered to me and the doctor gave me medicine that check the bleeding, but he forbade my working in the mill; so I parted with the labor that I love and that I had followed most of my life. My son David took me to Colonia Pacheco where I made my home with my wife Maria; and for two years of exercise I worked in the garden or with David or Morley. I rode the range helping to look after our stock.

I visited my children and my sons-in-law in Fruitland, New Mexico. While residing there and just before returning to Mexico, I attended the San Juan stake conference at Mancos, Colorado. Apostle Mathias F. Cowley was in attendance, and on the 16th day of May 1903, he ordained me a Patriarch and gave me a highly treasured blessing.

In the winter of 1906, in mounting a saddle horse, my gloved hand slipped from the horn of the saddle giving me a heavy fall. I had to be carefully nursed for three months. From 1906 and 1912 I remained at Pacheco and during that time, with the assistance of David and Morley, I built a good comfortable four-roomed brick house.

When the Civil War between Francisco I. Madero and Porfirio Diaz broke out, it was understood by both parties are people would remain neutral and they were assured he would not be disturbed; but when Huerta seize the reins of government and Venustiano Carranza took the field as leader of the Constitutionalists, conditions became so violent that President Wilson advised all Americans to leave Mexico. Still the Mormon colonists hesitated, hoping the war would soon pass in peace return without their having to abandon their homes. But it was not to be. As the strife went on, robbings and plundering’s of our people by both parties became so frequent, property rights were not respected, and life was not secure. Conditions were becoming unbearable, and it was feared resistance to unjust demands would be made and then a general massacre of the Mormon people might follow. To avoid that calamity it was deemed best to sacrifice their homes. On the 28th day of July 1912 just as our Sabbath meeting with closing, a messenger arrived and gave public notice that the entire community must be ready to leave at seven the next morning.

Wagons had to be coupled together and the best put on. Every vehicle in the town was brought out and put to use. At last when all was done that could be done in the darkness of night, the weary, anxious community sat down for a few hours rest. They were awakened by the rumbling storm that swept in fury over the mountain. All day it rain poured ‘til every hollow was a river and no move could be made; with the results of the days carrying would be, no one could tell. Monday night brought rest and then Tuesday morning bright and clear came, all accepted it as a good omen and the pilgrimage was started in a more cheerful mood. My son David P. Was made guide to direct the movements of the company. Thirty-two wagons were lined up all crammed full of the aged and the young but mostly with women and children, because many of the men were in the mountains looking after their stock. Promptly at 7:00 a.m. The train moved. With tearful eyes about 300 persons bade adieu to their earthly all, the homes of comfort and graves of their loved ones.

At Corrales we were joined by another small company of refugees. Then commenced in earnest a hard day’s drive of 30 miles to Pearson. Nine miles out a company of Red Flag Cavalry dashed across the road, haulted our train and demanded our guns and ammunition. Upon giving solemn promise of protection their demands were complied with and we were permitted to pass on. We reached Pearson without further interruption but too late to take the train for El Paso. The inhabitants of Pearson had abandoned their homes and they were thrown open to us. So we found a grateful shelter for the night.

On the 31st of July we were put on the cars at Pearson. There was a limited number of cars, and in order to take all the refugees, the cars were packed to the utmost limit of their carrying capacity. About 10:00 a.m. the train moved with the load of human freight and at sunset reached Ciudad Juárez. It was dark when they passed the Custom House and swept into El Paso. Here wonderful reception greeted us. Automobiles, streetcars and private vehicles were placed free for our service. Everything was done that could be done to make us welcome. We were soon transferred to a lumber yard two miles from El Paso where we were served a plentiful supper. True, we were proud, the multitude is great, and in the throng the sick, feeble and aged could not help but suffer. Several women were rushed to the hospital where kindly and skillful assistance given there saved mothers and babes. Soon after our camping in the lumber sheds we had a heavy rain and the yard became a mud puddle, making it very unpleasant for several days. I faced these discomforts and although I felt my strength failing, I made no complaint.

Harry Payne came and said, “Father Black, this is no place for you. You must go to better quarters.” I replied, “I must stay here for I have no money to go anywhere else with.” He leaned forward and whispered, “I remember seeing your name of the Tithing record. You are going to be cared for.”

The next day Apostle Ivins came and talked kindly with me. He called a Brother Sevey and directed him to take me and Maria and see that we were well cared for. The instructions were carried out. I remember with pleasure the Hotel Alberta where for eight days we rested and were treated royally. I feel thankful to the good citizens of El Paso for the aid and sympathy they gave us, and I feel thankful to our government and to President William H. Taft for the prompt appropriation of the magnificent sum of $100,000 to be used in giving aid to the American citizens who were expelled from Mexico. Of those, about 4,000 were Latter Day Saints and the hearts of all were gladdened by this generous assistance.

On the 10th day of August, Maria and I were furnished with a railroad pass that would take us to Price, Utah. There was sorrow mixed with joy when we parted our friends and fellow sufferers, the colonists. We had gone to Mexico in a common cause and for 25 years we had toiled together and had endeared to each other by sacrifices we had made. As a finishing touch to our experiences, we had drunk together from the bitter cup of expulsion from our homes. A two-day ride brought us to Price and to our children living in Huntington.

Patriarch William Morley Black died at 4:00 a.m., June 21, 1915 at Blanding, Utah. He left a wife and 28 living children, 214 living grandchildren and 206 great-grandchildren.

Submitted by Thora Bradford

Stalwarts South of the Border, Nelle Spilsbury Hatch page 42

I am very happy to be a living relative of Wm M Black 5th generation. He lived righteously and knew the truth when he heard it, this is what has made this family so great.