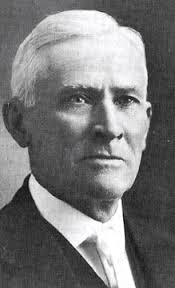

Anthony W. Ivins

(1852 – 1934)

Born September 16, 1832 in Toms River New Jersey, Anthony Woodward Ivins was the only son of Israel and Anna Lowrie Ivins. He and his parents were among the early pioneers to go to the Salt Lake Valley, arriving in 1853 when Anthony was but a year old.

When he was seven, his parents were called to help settle Dixie, as St. George and surrounding towns were then called. He had a half-brother, Will, and two half-sisters Edith and Maggie. In St. George Tony had what schooling could be gained, went rabbit hunting with a boyhood friend, followed his father about as he surveyed lands in and around St. George, and had a happy well-adjusted youth. It was there that he grew to manhood.

During these growing-up days he was at home on the range. His father acquired a large tract of forest land extending into the White Mountains in Arizona and soon had it stocked with a good breed of cattle. Tony did a lot of traveling to keep the hard within bounds. He spent as long as nine months away from home, never sleeping during this time in a bed other than what he carried on a pack animal. He had no food except what was cooked over a campfire. He took as good care of his gun as of his horse, and with his gun always handy could drop a deer in split-second timing at a maximum distance. He kept fishing tackle hand too and could easily angle enough trout for supper. The venison he broiled and trout he fried and the camp biscuits he made earned him an enviable reputation as a cook. His cattle-care travels took him into Apache land when they were on the warpath and constant vigilance was necessary to save both himself and his cattle. He was glad when they sold that eastern area and he could continue his cowboying closer to home.

He made his cowboy days serve him in becoming acquainted with what kind of game could be found where and when best to hunt it, how to read the weather and interpret wildlife behavior. He could read the stars, locate himself by night, and knew which peak in what mountains to use to orient himself. It taught him resourcefulness too. When his trousers wore thin and no others were available, he spread his canvas bedcover on the ground, ripped up his old worn-out pants, put them on it for a patter, and with his pocketknife cut out a pair of pants which when sewed together served the purpose, even if it was hard to tell whether he was going or coming.

Always in his bedroll, carefully wrapped but accessible, was his Book of Mormon from which in his leisure he methodically became acquainted with the forefathers of the friendly Piutes with whom he often visited. He analyzed the greatness of Book of Mormon prophets, sought to emulate such characters as Nephi, Alma, Mosiah, Benjamin and Moroni, and to use them as patters for a lofty adult life. Also, he carried books of history, tales of adventure and vicariously journeyed with explorers and mariners. Later in his life, when receiving an honorary LL.D. degree from Utah State College, he referred to this as his means of becoming acquainted with all parts of the world.

When at home he was active in both church and civic functions. He helped with programs, including drama in which he played leading roles. One story told in later years was of taking the play East Lynn to nearby Nevada mining towns, and portraying the part of the betrayed husband whose wife had digressed in a moment of temptation. His stern refusal to be swayed by her penitent plea for forgiveness moved one veteran miner in the audience to exclaim, “Oh, Tony, forgive her!”

When barely 23 years of age, Ivins was chosen to be one of the party under the leadership of Daniel W. Jones to carry the book of Mormon into Mexico and explore the country for sites suitable for Mormon colonization. Meliton G. Trejo, during the years 1874 to 1875, had translated nearly 100 pages of selected passages from the Book of Mormon into Spanish. With this and other tracts, the Jones expedition started south from Kanab, Utah in the autumn of 1875. They crossed the border at El Paso and penetrated as far south as Chihuahua City. The party then traveled west to the Sierra Madre Mountains, then worked their way north to the border area again. Among other locations, they passed through the Casas Grandes Valley where Mormon colonies would later be established.

After returning to Utah in mid-1876 and reporting their findings to Brigham Young, Ivins married his childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Ashby Snow, a daughter of Apostle Erastus Snow who had long presided as an ecclesiastical leader in the St. George area. The couple eventually became the parents of eight children. Every indication is that theirs was a lifelong, happy relationship. Shortly after the marriage, Ivins was called on another exploring-missionary venture to the Navajo and Pueblo tribes of Arizona and New Mexico. On this occasion, his companion was Erastus Beaman Snow. Well known for his mastery of the Spanish language, it is sometimes forgotten that Ivins also acquired partial fluency in Navajo and Piute. This particular mission was completed in less than a year.

In 1882, at the April conference of the Church, Ivins was again called as a missionary. This time was called again to go to Mexico City. The Mexican Mission had been opened by Apostle Moses Thatcher in 1879. Thatcher returned to the United States in 1881, leaving August H.F. Wilcken in charge. Ivins, now learning his 30th year, arrived and immediately undertook the challenging task of converting and baptizing all he could. During 1883 and 1884, he oversaw the mission himself. The challenges were enormous. The people seemed so lethargic and indifferent. Not only the Catholic Church but Protestant groups in and around Mexico City opposed their work. Sometimes Elders, in their zeal, fell athwart the law and Ivins had to secure their release. More difficult than anything was the loneliness he felt for home and family. During the spring of 1883, he wrote his wife of how much he wished he could be back “upon the barren top of Sugar Loaf with the July sun beating down upon me, contemplating dry, dusty St. George.”

Ivins returned from his mission in Mexico in April, 1884. Almost immediately he found himself caught up in a variety of activities while improving his growing properties. His involvement in the cattle business was especially remunerative, particularly in connection with his management of the Mojave Land and Cattle Company and the Kaibab Cattle Company with their ranches in southern Utah and northern Arizona. He also purchased a valuable strip of land along the Santa Clara River. In 1888 he was also favored as a political leader. At one time or another he held the offices of constable, city attorney, assessor and tax collector, prosecuting attorney, mayor, and representative to the state legislature. Ivins obtained the first grant given by the government to the Shebit (Shivwits) Indians and acted as Indian agent to them for two years. In 1895 he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention in Salt Lake City and was considered a leading candidate for the Democratic Party’s nomination to be the state’s first governor. It would be difficult to paint a more promising future than that facing Anthony W. Ivins in the mid-1890’s.

Then, in late August, 1895, he was notified that the First Presidency of the Church was calling him to succeed Apostle George Teasdale as President of the Mexican Mission. More than sacrifice in things political and economic would be involved. Ivins had friends and family in the St. George area that reached back 30 years. His aged parents lived there. All of this would have to be set aside. Beyond this, he had spent time in Mexico before and had not acquired a large affection for the land and its institutions. A considerable adjustment in his plans for the future would be required. It tells us much about the man’s commitments that he accepted the call and, with hardly a murmur, made arrangements to relocate in Mexico for an indefinite period of time.

On Sunday December 8, 1895, the Juarez Stake of Zion was organized and Ivins was introduced to the settlers as their new Stake President. He chose Henry Eyring and Helaman Pratt as his First and Second Counselors, respectively. Ivins then set out, with Apostle Francis M. Lyman and Edward Stevenson of the First Seven Presidents of Seventies, to visit the colonies and take measure of his new responsibilities. He also purchased the home that had been built by his father-in-law Erastus Snow, in Colonia Juarez and had it enlarged to meet the needs of his own family. This involved the addition of a red brick to the adobe used in the original structure and the construction of a bedroom, dining room and office in the back. When a frame kitchen and brick cellar were added to that, the house ran into the hill. On the bank of the east canal, behind the and above the house, he built a cistern and brought water through pipes into the house, the first one in the town to enjoy that luxury.

As Stake President, Ivins automatically inherited the job of vice-president and general manager of the Mexican Colonization and Agriculture Company, the firm that had been incorporated by the Church to oversee the purchase of lands and location of colonists in Mexico. This meant that he was almost constantly dealing with legal problems. His buckboard was seen frequently on the road from colony to colony and to Casas Grandes, the district municipality 10 miles distant. He was able to clear land titles and helped when land payments were in default. In the process of all this he became not only an acquaintance but a friend of leading men in the Republic. The expert skill he had acquired with the language as a missionary proved very useful. He spent time in the offices of President Porfirio Diaz, Chihuahua Governor Miguel Ahumada and Sonora Governor Luis Torres. In all cases, formal business attitudes relaxed into warm friendliness. He also became a friend of the Polish soldier of fortune, Emilio Kosterlitzky. Kosterlitzky was not only in charge of the feared Rurales of northern Mexico, a troop of rough frontier police, but exercised considerable influence in connection with land sales, especially in Sonora.

Difficulty arose early in 1898 concerning payments for the lands on which Colonia Oaxaca was located. President Ivins met with Kosterlintzky from whom the lands had been purchased. At the outset, no agreement could be reached. Ivins was able to assure Kosterlintzky, however, that the Mormons could be trusted to fulfill their contracts. After a trip to Salt Lake City where church’s financial backing was obtained, he returned to Sonora and consummated the arrangement, stating the colonists’ lands while impressing Kosterlintzky with his own honor. Kosterlintzky held such regard for Ivins and the colonists that he once offered to kill anyone the Mormons found troublesome.

President Ivins took the lead in getting the new Sonoran colony of Morelos established. He personally spearheaded exploration of the site which was located northwest and down the Bavispe River from Colonia Oaxaca. It was he who negotiated the terms of the land purchase from Colin Cameron, the Arizona resident who owned the site. I oversaw the survey of the area and directed where water should be taken from the river for the purpose of your getting land. He not only helps with laying out the town but took charge of recording the deeds and completing all legal arrangements in Hermosillo.

It is not generally known that President Ivins often advance his own funds to individuals in need, particularly when land or property were threatened by default. On one occasion he helped the entire community in this way. This had to do with the so-called Garcia lands on which Colonia Chuhuichupa was located. Ivins advanced what was needed to cover payments that had fallen behind and then went to Mexico City and paid off all remaining indebtedness. The role of the Stake President, as developed under President Ivins, went far beyond purely ecclesiastical functions.

Within the colonies, there was virtually no secular government apart from that provided by the colonists themselves. There were no city councils, mayors, courts or policeman. Provisions for the services provided by such offices felt entirely to the Church. Thus, regulations relating to irrigation, garbage, stray animals, police and fire protection, education and entertainment all were matters directed by the priesthood in the various Wards.

This meant that Ivins was ultimately brought into deliberations concerning these things throughout the Stake. Redivisions of lands, financial disputes between brethren, domestic quarrels, relationships between Mormons and Mexican authorities constituted more of his agenda than anything else. Water concessions were divided with the San Diego lands, 6 miles below Colonia Juarez, it was President Ivins who suggested a dynamo be installed to produce electricity from the natural fall of the water. The Mormon communities became the first in their part of the country to enjoyable electricity and telephone service.

The Ivins family not lived on the western side of the Piedras Verdes River long before they realize the great inconvenience of having the town divided when the river was a flood stage finally, when the town had been separated by raging river for three days and the swinging bridge been torn from its moorings, Ivins invited Samuel E. McClellan to put his skills as a builder to work and do something about it. President Ivins promised that men and means would be supplied to whatever extent McClellan required. Work on the wagon bridge then commenced and the pillars built under McClellan’s direction are still doing service today for the steel and concrete bridge that connects the highway running through Colonia Juarez.

At the first meeting held after his arrival to consider educational matters, Ivins proposed in the largest but centralized program for Colonia Juarez as the education center for the entire Stake. In April, 1896, he asked the First Presidency of the Church for financial support for the plan and for an educator who could synchronize and oversee the schools of the colonies. The First Presidency pledged their assistance. And, through Dr. Karl G. Maeser, President of Brigham Young Academy, Ivins was placed in contact with Guy C. Wilson, then a student at the Academy in Provo. Arrangements were made for Wilson to assume his responsibilities in Colonia Juarez in September, 1897. When by 1904, the influx of students overwhelm the school space available in Colonia Juarez, President Ivins donated five acres of his own land in the town on which to construct a larger Academy building. By the autumn 1905, the academy, then a four-year accredited high school, opened its doors in a new double story building surrounded by spacious a campus. This was a large step forward for the entire Stake. Five of President Ivins’s own children graduated from this institution.

Ivins also provided an example of what can be done with one’s own home and surroundings. During the first 10 years of the colonies’ existence, too many of the houses had remained in an unimproved condition. Even fences were often primitive and near collapse. Ivins feel the shard with imported fruit and ornamental trees. Choice shrubs, fronted by a heart-shaped lawn surrounded by hybrid tea roses and dahlias, inspired everyone in Stake to imitate his efforts. Inside his home, he covered the floors and carpets, and in every room and wallpapered every wall. His own office was furnished in natural cedar. A veranda was supported by massive pillars and banisters. The inside of the house was trimmed with fancy, intricate woodwork. His blooded horses, Jersey cows and imported chickens were housed in attractive barns and outbuildings.

Another aspect of Ivins work in Mexico had to do with the performance of plural marriages. After President Woodruff’s 1890 Manifesto, Church authorities felt it best that such polygamist contracts as occurred should, when possible, be performed outside United States. The Mexican colonies had been used as locations for such ceremonies even before President Ivins arrived in 1895. With authority given him by the First Presidency, he was sometimes called upon the seal couples in such relationships. Although he himself never took a plural wife, he may have occasionally felt uncomfortable with his role in such things, faithfully executed his charge in these matters. It must be pointed out that he was most circumspect in requiring that any couple requesting this privilege present him with appropriate papers indicating that they had received prior approval from authorities in Salt Lake City. It should also be remembered that the monogamous marriages he performed far outnumbered the polygamist sealings he performed. And with President Joseph F. Smith directed that no plural marriages were to take place anywhere in the world after 1904, Ivins strictly adhered to the new policy.

For those a new President Ivins, perhaps nothing so characterized him as his love of nature. The sensitivities he acquired as a cowboy never left him. One of the ways he found to share his feelings with his family was to take them on an outing for two weeks each year. Usually, they went to North Valley, a picturesque fishing center a few miles north of Colonia Chuhuichupa. When he had his killer deer or massive fish, he put his gun and tackle away, no matter how many good shots presented themselves or how well the fish were biting. Killing for the sake of killing was to him unsportsmanlike and his family was taught his creed. The conference was usually held in Chuhuichupa Ward at the time of these vacations in the colonists of the region enjoyed close contact with the Stake President and his family on these occasions.

Ivins love for the outdoors also found expression in his many talks before Church audiences. Initially, and in later years, he wrote articles, chiefly in Church magazines, incorporated his outdoor experiences. One series was entitled “Traveling our Forgotten Trails.” These pieces included accounts of the route followed by the Mormon Battalion, experiences of the U.S. Army in Mexico during the trouble with Poncho Villa, and other essays having their setting in Mexico. The subject of one of the articles was especially popular with audiences as a theme in Ivins’s many sermons. This was a story of a mother mockingbird known to the Ivins family during their time in Colonia Juarez. The birds sang beautifully for them every summer. But during a sudden hailstorm, she allowed the life to be beaten out of her body rather than expose the brood she covered to the murderous hailstones. The lessons of fidelity and love that were drawn from this experience were seldom lost on those who heard it.

Another article dealt with the sequel to the tragic Thompson massacre, an event to touch the hearts of everyone in the colonies. A band of Apaches attacked a family of Mormons and Pratt ranch in the mountains in 1892. The mother and one of her sons were killed, the renegade escaping with their loot. Eight years later members of the band were cited and shot near Colonia Pacheco. President Ivins was in Pacheco at the time and examine the bodies of the dead Indians. From the workmanship on their moccasins and quivers, as well as a birthmark on the face of one of the Indians, he was convinced that it was none other than the “Apache Kid,” the notorious leader of the band believed to be responsible for the Thompson massacre. The article was titled “Retribution.” The article was titled “Retribution” because, in Ivins’s words, “He killed Mormons and by Mormons was killed.”

They are sowing turn-of-the-century saw the colonists grow both in numbers and prosperity. The same year saw the Mormon colonies acquire a reputation throughout the Church is one of the most faithful bodies of the Saints to be found anywhere. The level of their tithes and offerings were among the highest in the Church. There was much for which Ivins could feel pride. After spending so much time there, he must have also felt a growing attachment to Mexican society. Certainly, the bonds that developed between himself and the Mormons residing in Mexico were strong affectionate. Yet, he and Elizabeth both longed for returned to life in the United States. It was doubtful, however, that he anticipated what it was that would bring about the return.

In 1907, while attending the general conference of the Church in Salt Lake City, he sat busily taking notes, as was his habit, in one of the many small notebooks he kept. As the names of the general authorities were presented for approval by the membership of the Church, he proceeded to write their names as they were called. Then, suddenly, he realized he had written his own name as one of those submitted as a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. It was proposed that he take the place of Elder George Teasdale who had died. It will be recalled that it was Apostle Teasdale that he succeeded as the presiding officer over the Saints in Mexico in 1895. Ivins was ordained to the new position before returning to the colonies. He had served for 12 years as President of the Juarez Stake.

After making preparations to leave the colonies, including assistance with the selection of Junius Romney as his successor, Ivins and his family relocated to Salt Lake City where they resided for the rest of their lives. Despite his responsibilities in connection with the Apostleship, special ties with the colonies continued. One of his daughters had become the plural wife of Guy C. Wilson and was yet living there. There were also investments in properties and mines that he had made while in Mexico. Leaders in Salt Lake City looked to Ivins for advice concerning the colonies and, for the balance of his life, he made frequent visits to them.

With the coming of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 he gave especially close attention to affairs in the colonies. When roving bands of soldiers began to abuse the Mormons, he told the Saints: “I have seen this coming for years, and no one can say how long it will last. But my advice is to stay perfectly neutral… You may be despoiled and robbed, but if you stay close to the Lord, take part with neither side, I promise that if you will lose your lives.” Although there were some trying times and close encounters in the period before the 1912 Exodus, no colonists died at the hand of a soldier.

When the evacuation of the colonists actually took place, Ivins was in Ciudad Juarez to meet the first trainload of women, children, and aged men, and stayed until the last evacuees arrived. He helped negotiate with the City of El Paso for food for the homeless and with Fort Bliss for use of tents as a more adequate shelter than the lumber sheds in which they were temporarily house. When it looked unfavorable for a return to their homes in Mexico, he was partly responsible for obtaining free rail passage in the United States for all who cared to relocate elsewhere. He continued to visit and encourage those who did return to the colonies. And, he was instrumental in affecting the reorganization of the Stake, placing Joseph C. Bentley in charge and setting apart new Bishops in Colonia Juarez and Colonia Dublan.

As a General Authority, he worked in a variety of capacities including President of Utah Savings and Trust Company, President of the Board of Trustees for Utah State Agricultural College, and was a member of the National Boy Scout Committee. He was also chosen as an official spokesman for the Church on issues of the day when such matters called for a Church response. In March, 1921, Ivins became second counselor to President Heber J. Grant. The two were first cousins and had long maintained a close friendship. Now they work together almost daily. In 1925 Ivins was named First Counselor. Through it all, he continued to find time for his broad range of interests, from archaeology and Indians to hunting, fishing and history. He seemed to have been universally admired by all who knew him.

President Ivins died suddenly on September 23, 1934. He had celebrated his 82nd birthday but a week earlier. As Ann Hinckley and Mary Fitzgerald of the Utah State Historical Society have mentioned, in addition to his funeral in the tabernacle, the Piute Indian tribe honored him with a special memorial of their own. Perhaps no better summary of life can be found than an Indian beadwork message sent to him in 1932: “Tony Ivins, he no cheat.”

His beloved companion was united with him in death 18 months later on March 22, 1936.

Carmon Hardy and Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

Stalwarts South of the Border page 310

A great tribute to a great leader. As a youth, I often heard the respect in the voice of my parents and other colonists who knew him when they spoke of him. Thanks for another interesting edition!

Paul Hatch